With an outlook for continued economic growth and lower inflation in 2025, it feels like we have finally emerged from five years of economic turbulence in a better position than we might have feared along the way.

Employment levels have remained high, and we have not seen a wave of loan defaults and asset repossessions. Although commercial real estate values have fallen and forward IRRs are nudging above the cost of capital, investment volume is still low.

It seems like a good time to ask: Where are we in the cycle?

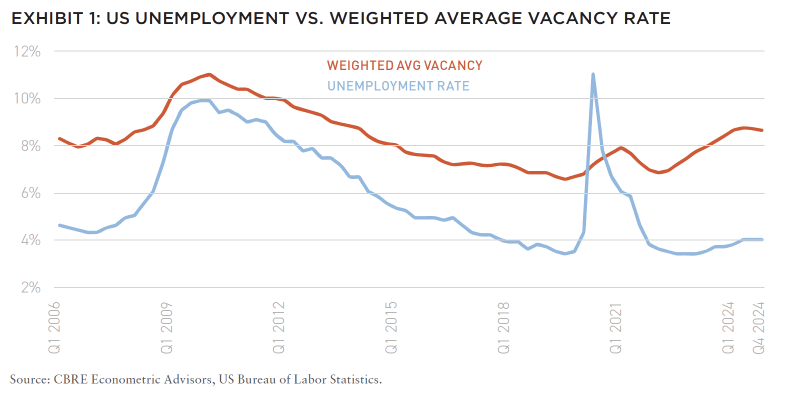

Exhibit 1 shows the situation. Unemployment is low and the average aggregate real estate vacancy rate has stabilized, so it seems we are late in the economic cycle and at the start of a new one in real estate. That’s a tricky situation for real estate investors.

Returns look attractive but are we too late in the economic cycle to be certain about rent levels and NOI growth? Are we investing in an economy that is overdue a recession? Is it possible that the effects of the pandemic and the subsequent economic policy response have set the table for a further period of economic expansion? Is unemployment still the best indicator of the overall economic cycle?

This article will answer these key questions.

THE ECONOMY

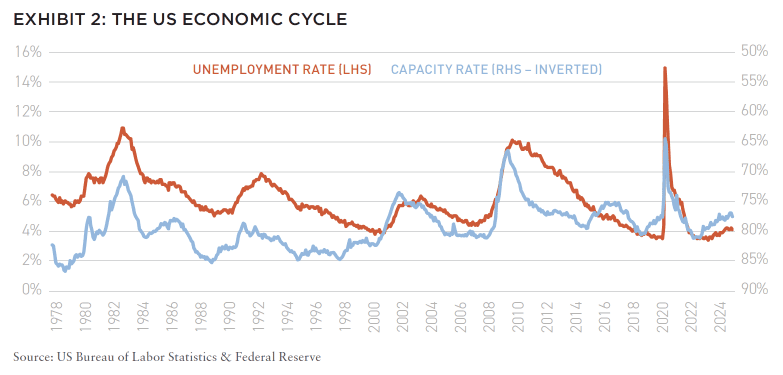

The unemployment rate over the past 40 years has been a remarkably consistent indicator of the economic cycle, characterized by six to nine years of economic expansion with hiring outpacing the growth of the labor force, followed by one to two years of economic contraction with a marked slump in the demand for labor (Exhibit 2). Capacity utilization—a measure of how much of a nation’s aggregate production potential is being used—is another cyclical indicator with a more sensitivity to mid-cycle slowdowns and follows a similar pattern.

Each of the past four cycles has been slightly different due to changes in regulation, the politics of the time and most importantly the sectors that over-expanded. Generally, over the course of each cycle, the output gap closes and turns positive, creating inflationary pressure. In response, central banks raise interest rates—usually not soon enough—and asset prices collapse, leading to some form of credit crunch. This is followed by a drop in consumption and then a surge in job losses. The worst is over when companies’ profit margins are restored, and employment stabilizes. Inflation and Interest rates fall, and proactive fiscal policy gets the next cycle going. It is not completely clear why action by central banks always lags the cycle and growth in certain sectors gets out of control.

If we accept this standard cyclical pattern and consider the current level of unemployment, it appears that we are close to the end of the current economic cycle. However, inflation and interest rates are coming down, capacity utilization is some way off its cyclical peak and there are no obvious asset bubbles or over-leverage in the economy. These factors suggest that the economy is only mid-cycle, despite the very low unemployment rate, with several years of economic expansion ahead.

Three factors suggest that the unemployment rate might not be such a clear end of cycle indicator as it has in the past: structural change in the labor market, the long-term effects of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the impact of pandemic-era policies.

The US labor participation rate is at a 40-year-low 62% since peaking at 66% at the end of the long boom of the 1990s. The older, less geographically mobile part of the population has been unable to adapt to the decline of manufacturing and growth of service sector jobs, many in the digital economy. Immigration has been profoundly strong over the same period, with 7.8 million more people in the U.S since 2010 and more than a third of which came between 2019 and 2023. As a result, the U.S has a reserve workforce that can be accessed when labor demand is high, substantively reducing inflation pressure at low levels of unemployment.

The long-term impacts of the GFC are twofold, both indirect. The GFC was so deep and the effects on consumers so severe (unemployment, loss of homes, negative home equity) that for the decade afterwards they paid down debt and reduced leverage. Very unusually, after 10 years of economic expansion since 2009, household balance sheets remained in very good shape. This alone suggests and extended cycle may be possible.

The second impact was due to politics. The hostility to political elites that developed due to the banking sector bailouts during the GFC helped usher in a period of fiscally liberal populism. Western governments had to spend heavily to protect ordinary households during the COVID pandemic, and this largesse has continued. This led to a jobs and savings bonanza that has left households in much better financial shape than at the end of the past three cycles. The household sector still has enough spending capacity to maintain the current cycle for some time.

The extraordinary and in hindsight excessive fiscal and monetary stimulus that was rolled out during the pandemic has had several profound effects, particularly the refinancing of the private sector. While households refinanced their mortgage rates at 2% to 3%, businesses also locked in cheap long-term debt. As a result, the private sector not only survived the sharpest rise in interest rates in 40 years but thrived. The hyper vigilance of the Fed and its liquidity support also allowed the banking sector to refinance itself through credit-loss provisions. Since 2022 the banking sector has made approximately $120 billion of provisions against losses.[1]

On the face of it, low unemployment suggests the economic cycle is near an end. However, a deeper analysis suggests this economic expansion probably has much farther to run. What are the risks and opportunities?

Risks:

- Inflation is more likely to surprise on the upside than the downside. Even if the unemployment rate is less meaningful than it used to be, the labor market is still tight.

- Some elements of the Trump administration’s policy package appear inflationary. There are 8 million job openings in the US and stricter immigration enforcement could worsen the labor shortage. Tariffs, if broadly applied, will increase prices in the short and medium terms and may raise business costs in the longer term by forcing production to move from lower- to higher-cost locations.

- A more inflationary environment, alongside the continued imbalance of government spending over taxation. will likely lead to higher-for-longer interest rates. High interest rates are always a feature of a late-cycle environment and may not hinder growth too much. However, there is an elevated risk of rapid financial tightening, including a continued surge in the US dollar’s value.

Opportunities:

- Consumer and business balance sheets are unusually strong for this stage of the cycle and consumers could easily take on more debt, which would be positive for consumption.

- Business investment, particularly in AI technologies, and the tight labor market could easily drive a longer period of productivity growth, reducing inflationary pressures and extending the cycle. Some elements of Trump’s policy initiatives, such as deregulation and corporate tax reduction, would support this trend.

- The global economy is in reasonably good shape. Falling inflation and interest rates in Europe and the U.K. likely will stimulate a modest but broad-based consumer recovery. China, which has a collapsed housing market and weak domestic consumption, is applying a sizable amount of stimulus to maintain economic growth.

THE REAL ESTATE SECTOR

The rise in the average aggregate vacancy rate marks the end of the most recent real estate cycle. It is a very unusual situation. Over the past 40 years, the end of the real estate cycle has always been at the end of the macro cycle, so real estate has suffered a very large drop in demand at the same time as new completions were elevated. In this cycle, real estate demand did weaken in response to the rise in interest rates, but except for office space has picked up quite quickly due to resilient GDP growth. The current rise in vacancy is mostly related to the cyclical surge in completions, especially in the multifamily sector.

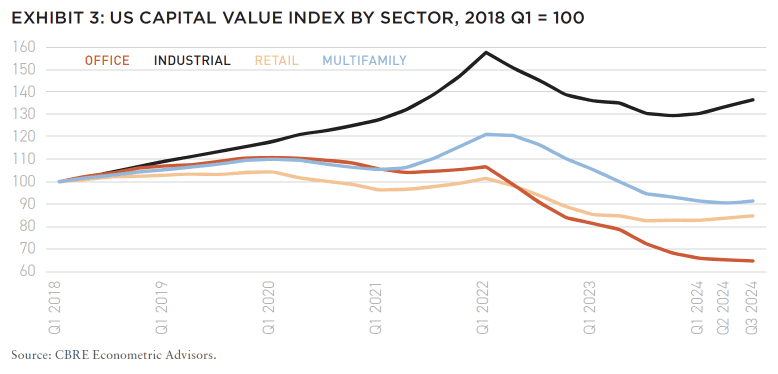

Falling values, the other classic feature of the end of the real estate cycle, are also occurring (Exhibit 3). Values would probably have fallen due to the rise in vacancy, but the sharpest rise in interest rates in 40 years and a real-estate-specific credit crunch have exacerbated the situation. Although real estate prices seem to be bottoming, it is possible that further value adjustment is required to bring investor demand back into line with investment supply.

How quickly will values recover? While the cyclical fall in vacancy that we anticipate over the next 12 to 24 months will be positive for values, a full recovery will not occur for at least the next five years. Debt financing for real estate investment is available from banks, institutions and debt funds, but rates are higher and loan-to-value (LTV) ratios lower than they were prior to 2022.

Moreover, there is a large legacy of real estate losses that remain unbooked and unprovided for by the regional and community banking sector. Refinancing US real estate is proceeding in an orderly fashion, thanks to economic growth and Fed and FDIC supervision, but it is very much a work in progress. As the wall of commercial real estate loan maturities grows, higher interest rates increase the pressure on borrowers needing to refinance. S&P Global estimates that roughly $950 billion of US commercial real estate loans will mature in 2025.[2] Although most of these loans will be refinanced, some will default and create a drag on value growth.

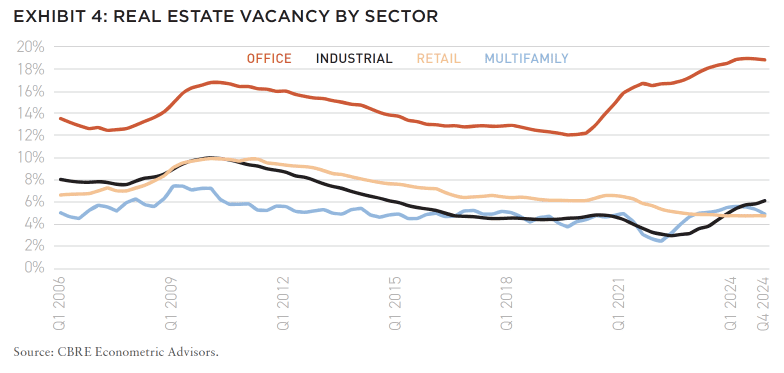

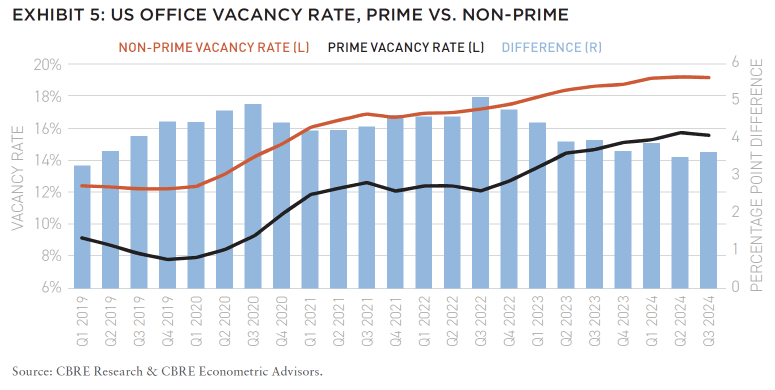

Not all the movement in real estate values can be explained by the cycle and interest rates. Longer- term structural shifts also are a contributing factor. Exhibit 4 shows the structural shift in office usage due to hybrid working. The surge in office vacancy has been an order of magnitude higher than that of the industrial and multifamily sectors. CBRE estimates that there will be a permanent reduction in demand, which makes it likely that 10% to 15% of total US office inventory is obsolete. While it is likely that office values will be the slowest to recover of any sector, higher-grade office assets will recover much more quickly than the average and could well provide the best returns of all sectors in the short and medium terms (Exhibit 5).

Hardly any cyclical change can be discerned in the retail sector. Vacancy has trended down, with very little additional retail space added to the market over the past 15 years and a long-term structural shift to online sales and direct delivery. Americans spending more time near home has translated into greater retail sales at strip and neighborhood centers in prominent trade areas.

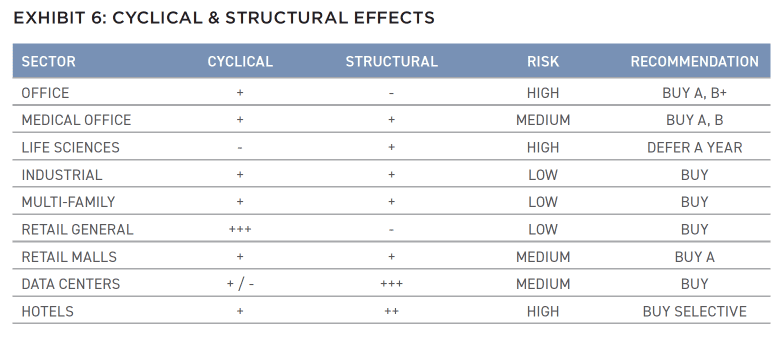

Office and retail are not the only sectors experiencing a blend of cyclical and structural effects (Exhibit 6).

LOOKING AHEAD

Despite appearing late cycle, a mix of longer term and pandemic effects means that the macro economy may grow for several more years. From a real estate perspective, there has hardly been a better time to acquire real estate in the past 15 years. Virtually every commercial real estate sector is a buy, either entirely or selectively.

Nevertheless, investors will have to bide their time for material capital value appreciation. A combination of higher-for-longer interest rates and certain bank loan workouts will keep the cost of capital high for several years. This real estate cycle will be about creative management for cashflow growth and adapting to structural shifts in occupier demand. This will all be made easier than it sounds because the drop in new construction starts that has accompanied this downturn in the real estate cycle likely will be prolonged.

NEW: SUMMIT #17

+ EDITOR’S NOTE

+ ALL ARTICLES

+ PAST ISSUES

+ LEADERSHIP

+ POLICIES

+ GUIDELINES

+ MEDIA KIT

+ CONTACT

WHERE ARE WE IN THE CYCLE?: OVERVIEW OF THE US ECONOMY AND REAL ESTATE SECTOR

Richard Barkham + Jacob Cottrell | CBRE

COMPELLING OPPORTUNITIES: MAKING A CASE FOR US REAL ESTATE

Karen Martinus + Mark Fitzgerald + Max von Below | Affinius Capital

OPEN WINDOW: WHY NOW IS THE TIME TO INVEST IN COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE

Chad Tredway + Josh Myerberg + Luigi Cerreta | JPMAM

NORMALIZING MOVEMENT: POPULATION MOVEMENTS NORMALIZING AFTER COVID-19 SHOCK

Martha Peyton + Matthew Soffair | LGIM America

CHRONIC SHORTAGE: THE US HOUSING SCARCITY WILL BE LIKELY TO PERSIST FOR SEVERAL YEARS

Gleb Nechayev | Berkshire Residential Investments

FLORIDA FOCUS: PRODUCTION INDEX BELOW 50 CURIOUSLY SIGNALS OPPORTUNITY

Rafael Aregger | Empira Group

WHOLESALE CHANGE: DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGES AND STAGNANT INVENTORY CREATE NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR RETAIL

Stewart Rubin + Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

GAME CHANGE: INFRASTRUCTURE GROWTH ACCELERATING WITH AI

Jon Treitel | CBRE Investment Management

FOR THE TREES: MASS TIMBER INTEGRATION IN INDUSTRIAL REAL ESTATE

Mary Ellen Aronow + Erin Patterson + Caroline Suarez + Cassidy Toth | Manulife Investment Management

BORDER INDUSTRIAL: INVESTING IN US/MEXICO BORDER PORT INDUSTRIAL MARKETS

Dags Chen, CFA + Lincoln Janes, CFA | Barings Real Estate

RESILIENCE AMIDST UNCERTAINTY: HOW ISRAELI AND UKRAINIAN INVESTORS ARE ADAPTING REAL ESTATE STRATEGIES DURING CONFLICT

Asaf Rosenheim | Profimex

CYBER RISK VIGILANCE: HOW REAL ESTATE DIRECTORS AND BOARDS CAN GUARD AGAINST CYBER RISK

Marie-Noëlle Brisson, FRICS, MAI + Michael Savoie, PhD | CyberReady, LLC

ALTERNATE REALTY: DIGITAL RIGHTS MANAGEMENT FOR REAL ESTATE AND AUGMENTED REALITY

Neil Mandt | Digital Rights Management + Steve Weikal | MIT Center for Real Estate

DRIVING FORCE: UNDERSTANDING SYNDICATED LOANS AND MULTI-TIERED FINANCING

Gary A. Goodman + Gregory Fennell + Jon E. Linder | Dentons

HOUSING COMPLEX: CUTTING-EDGE APARTMENTS ARE A CATALYST FOR A MORE PROFITABLE FUTURE

Alejandro Dabdoub | AOG Living

NOTES

1. “US bank credit loss provisions soared in 2023 as credit concerns intensified,” S&P Global, Feb. 21, 2024.

2 “Commercial real estate maturity wall $950B in 2024, peaks in 2027,” S&P Global, Sept. 5, 2024.

THIS ISSUE OF SUMMIT JOURNAL IS GENEROUSLY SPONSORED BY

/ EXECUTIVE SPONSOR

AOG Living is a leading fully integrated, multifamily real estate investment, construction, and property management firm headquartered in Houston, Texas. AOG Living has acquired, built, or developed more than 20,000 multifamily units with a total aggregate value of over $2.4 billion and has a growing portfolio of more than 35,000 apartment homes and 170+ properties under management throughout the nation. Learn more at aogliving.com.

Vertically integrated owner, operator, and developer of Sunbelt multifamily. Partnering with institutions on a single-asset and programmatic basis. 28k+ units acquired and developed. 62k+ units under management. 1,500+ associates. 8 Sunbelt states. To learn more, visit hrpinvestments.com and hrpliving.com. And for more information, contact john.duckett@hrpliving.com.

Affinius Capital is an integrated institutional real estate investment firm focused on value-creation and income generation. With a 40-year track record and $64 billion in gross assets under management, Affinius has a diversified portfolio across North America and Europe providing both equity and credit to its trusted partners and on behalf of its institutional clients globally. To learn more, visit affiniuscapital.com.