Some recent research argues that more direct approaches to real estate investing can more effectively address the characteristics, opportunities, and risks associated with the current state of commercial real estate.

Recent research has found that closed end real estate funds, in aggregate, have broadly underperformed over the past two decades. In particular, Private Equity Real Estate (PERE) funds have not delivered acceptable net returns relative to alternative opportunities, risks, and fees.

Most of the research on this topic has focused on US funds, but there is increasing focus on non-US and global funds. With this in mind, this article examines the research and its implications, looks at potential causes, and evaluates alternative approaches for non-US investors looking to invest in US real estate.

In particular, this article argues that more direct approaches to investing in real estate more effectively address the characteristics, opportunities, and risks associated with real estate.

WHAT THE RESEARCH SAYS

Recent studies that have evaluated closed end real estate private equity fund performance have concluded that the value proposition has, on average, been lacking. Closed-end funds have generated negative alpha for investors; have often not out-performed leveraged core strategies or REITs; and have significantly higher fees than alternative investment vehicles. Finally, there is evidence that managers manipulate values and returns in order to improve subsequent fundraising efforts.

This research is especially relevant, as closed end co-mingled funds play an important role in most institutional real estate portfolios. Hodes Weil reports that closed-end funds remained the most popular investment product for institutions in 2023, with 80% of all survey participants expressing interest. This level of interest is close to an all-time high, while the next closest product (open-end funds) garnered only 56% interest.1

Below is a summary of the recent papers that have generated these findings:

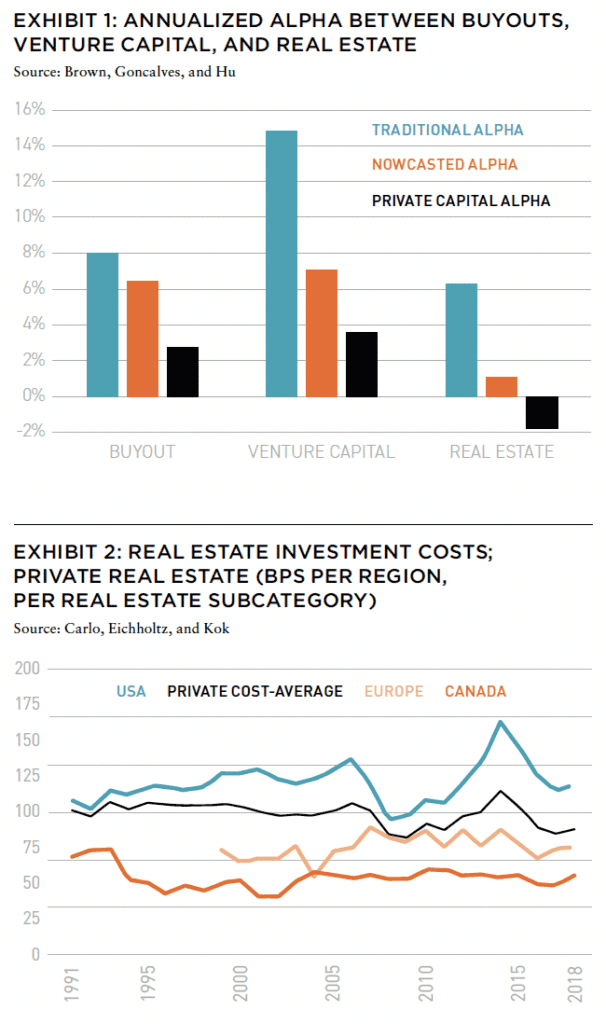

- Brown, Goncalves, and Hu, have created a measure of alpha that addresses the fact that PE returns reflect fund-level, and not overall performance in a portfolio context and are not comparable to alphas used for other asset classes. As shown in Exhibit 1, real estate’s “private capital alpha” is negative and significantly worse than other PE options, based on simulated portfolio returns.

- A recent paper by Da Li and Timothy Riddiough, “Persistently Poor Performance in Private Equity Real Estate,” finds that real estate funds generate negative alphas, and do worse over later vintages, and that this is specific to RE and not the case for the rest of the private equity industry.2 Real estate funds generated Internals Rates of Return (IRR) direct alphas (both based on liquidated funds with vintage dates through 2011) that were inferior to both Buyout (BO) funds and Venture Capital (VC) funds. Perhaps more surprising was the finding that firm experience does not lead to improved performance: “RE fund performance deteriorates significantly after the fourth fund offering,” again in contrast to other private equity sectors that demonstrate improved performance with additional fund offerings.3

- “Another Look at Private Real Estate Returns by Strategy.” by Bollinger and Pagliari (2019) repeats Pagliari’s prior research using different data sources.4 Net returns were reasonable for all investment styles, but alpha metrics value add and opportunistic funds were both negative. They also calculated that investors could have added leverage to core funds to generate comparable risk-adjusted returns, resulting in approximately 3% per annum in additional returns.

- “Catering and Return Manipulation in Private Equity,” a working paper by Jackson, Ling, Naranjo (2022), provides evidence that “private equity (real estate) fund managers manipulate returns to cater to their investors.” They suggest that investors may even be happy with overstated and smoothed returns.

- In “Private Equity Real Estate Fund Performance: A Comparison to REITs and Open-End Core Funds,” Arnold, Ling, Naranjo (2021) find that closed end funds underperformed REITs and had comparable performance to NFI-ODCE, despite generally higher risk, over the 2000–19 period.

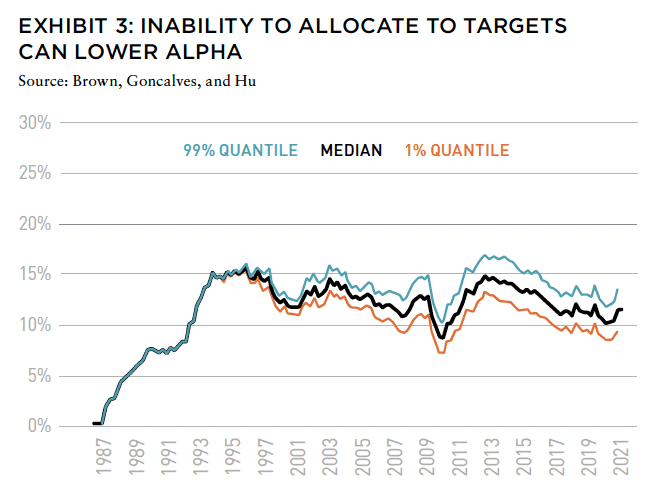

- Carlo, Eichholtz, and Kok (2021), in a PREA-sponsored report entitled “Three Decades of Institutional Investment in Commercial Real Estate,” found that pension funds in the US pay more to external real estate managers than their peers in Canada and Europe. (see Exhibit 2) In addition, investments costs (not including carried interest and promotes) averaged 180 BPS for external approaches, compared to 35 basis points for internal approaches.

- In “Performance of Non-Core Private Equity Real Estate Funds: A European View (2015),” Sami Kiehelä and Heidi Falkenbach found that PERE funds that invested in Europe delivered an average (median) IRR of –1.3%.5

There are other papers and articles that have addressed private real estate closed end fund performance. Those that we have reviewed have come to generally similar conclusions.

OTHER PROBLEMS WITH CLOSED-END FUNDS

In addition to low net returns and high fee loads, academics also observe other shortcomings of closed end real estate funds that have long created heartburn for investors:

- Lack of control: Once committed to a fund, limited partners typically have no input into investment strategy, pacing, management, leverage and exit timing.

- Illiquidity: Interests in closed end funds are highly illiquid. Although a secondary market exists for some funds, pertinent information regarding fund prospects can be challenging. Lack of transparency can lead to value discounts.

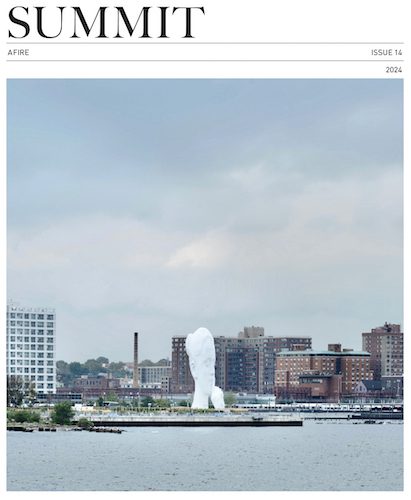

- Allocation and Rebalance Risk: For private equity funds in general and real estate funds in particular, it is very difficult to anticipate or forecast both capital calls and distributions. Inability to allocate exactly the target allocation is an important risk that lowers alpha. Brown et al. found that under-allocation is common (Exhibit 3).

- Alignment of Interests: By definition, managers are motivated to generate incentive fees. Since incentive fees are typically tied to IRRs, managers have an incentive to maximize IRRs through delayed capital calls, subscription line financing and early dispositions, often to the detriment of investment multiples.

- Cycle Mismatches: Real estate is inherently cyclical and defined by the inelasticity of supply and elasticity of demand. Managers—who have businesses to run—need to raise funds on a continual basis, which includes poor vintage periods. Admittedly, funds deploying capital during or after downturns and selling before the next downturn tend to do fairly well, but those opportunities are rare and difficult to time.

- Complexity: One of the primary forms of value creation in real estate—development—takes a long time, particularly if it runs into snags related to entitlements, construction, or the market, and therefore only comprises a modest portion of opportunistic funds. Even well-conceived projects that could ultimately be successful can sink a fund if the timing is off. Other forms of value creation—leasing vacancy, improving operations, growing rents, and so forth—can be achievable during a typical fund investment period, but generally move the needle more modestly.

WHY CAN CLOSED-END FUNDS UNDERPERFORM, AND WHY DO INVESTORS OFTEN IGNORE THIS?

The academic research leaves two obvious follow-up questions without satisfying answers:

- Why do real estate funds underperform most private equity strategies?

- Why do investors continue to invest in an underperforming category?

To the first question, many observe that real estate investments lack access to the level of “engineering gains” available to private equity (such as Buyout and Venture Capital).6 Real estate offers fewer opportunities to increase income or financially engineer, with fewer potential exit paths. In addition, as we comment above, two of the more meaningful paths to create value—development and redevelopment—frequently are not feasible within closed end fund timeframes or, when they are pursued, give up much of any alpha generated to operating partner fees.

As to why investors continue to allocate to an underperforming category, academics seem mystified. Li and Riddiough observe that public pension funds are more dominant investors in real estate funds relative to BO and VC funds, and tentatively conclude that this must have something to do with it, euphemistically concluding that public pension investors seem to be “maximizing something other than investment returns.”7

We can’t conclude that pension fund investors make inferior decisions relative to other institutional investors. It seems more likely that the data challenges that academic researchers are working to address and mitigate are major contributors to seemingly irrational decision making: investors in closed end real estate funds have not had sufficient information to conclude that they were underperforming. In addition, investors probably have not had enough alternative options.

IN THIS ISSUE

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR: WELCOME TO #14

Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

INSURING FOR ELSEWHERE: CLIMATE-RESPONSIVE REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT

Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

INSURING FOR ELSEWHERE: STRIPPING THE CASHFLOW FROM THE DEAL

Paul Fiorilla | Yardi

MARKET OUTLOOK: MODEST GROWTH AND RETREATING INFLATION IN 2024

Martha Peyton, CRE, PhD | LGIM America

UNDERPERFORMANCE PARADOX: NEW RESEARCH QUESTIONS THE VALUE OF PRIVATE REAL ESTATE FUNDS

William Maher, Taylor Mammen, Ben Maslan | RCLCO Fund Advisors

NAVIGATING THE CURVE: RESILIENCE, ADAPTATION, AND PREPARING FOR 2024

Jack Robinson, PhD | Bridge Investment Group

LIQUIDITY FREEZE: POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS FOR COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE

Christopher Muoio | Madison International Realty

SUPPLY WAVE: REASON FOR OPTIMISM IN THE MULTIFAMILY SECTOR

Sabrina Unger, Britteni Lupe | American Realty Advisors

MANAGE WHAT YOU MEASURE: UNDERSTANDING EXPENSE INFLATION IN APARTMENTS

Gleb Nechayev | Berkshire Residential + Webster Hughes, PhD | ThirtyCapital

PARSING OFFICE DISTRESS: PLANNING FOR THE NEXT GENERATION OF OFFICE SPACE

Dags Chen, Lincoln Janes, CFA | Barings Real Estat

MODEL STATES: USING ECONOMIC STATE MODELS TO ASSESS THE US OFFICE OUTLOOK

Armel Traore Dit Nignan | Principal Real Estate

OUTWARD SHIFT: WILL THE LOGISTICS SECTOR CONTINUE TO OUTPERFORM?

Kerrie Shaw | AXA IM Alts

HARNESSING THE WIND: TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE AND THE PROMISE AND PERIL OF AI FOR REAL ESTATE

Nikodem Szumilo | University College London + Chris Urwin | Real Global Advantage

MIND YOUR DATA: REAL ESTATE INVESTING, FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF A DATA NERD

Ron Bekkerman, PhD

OPERATING EXPENSES RISING THE OTHER MAJOR COMPONENT OF NOI GETS MORE FOCUS

Stewart Rubin, Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

IN MEMORIAM: JANICE STANTON

+ LATEST ISSUE

+ ALL ARTICLES

+ PAST ISSUES

+ LEADERSHIP

+ POLICIES

+ GUIDELINES

+ MEDIA KIT (PDF)

+ CONTACT

COMMONLY SUGGESTED ALTERNATIVES

Among the articles critical of closed-end funds, the most commonly suggested alternatives are 1) levering up core real estate (to enhance returns) and 2) REITs.7 Both of these approached should be given strong consideration by non-US investors but are unlikely to be the full answer.

Investors can apply additional debt to core real estate by increasing the loan-to-value ratio across directly-owned properties or portfolios, or by investing in core funds through both equity and debt (potentially secured by the institutional fund). Most investors are too small to own real estate directly (or face negative tax consequences in the case of non-US investors), and/or may not have the mechanism or policy approval to lever core funds. Other drawbacks to core funds include:

- Investing in core funds offers limited opportunities to make property type or geographic bets: investor delegate all allocation discretion to the fund, hoping that the manager makes good market decisions. (The recent growth of property-specific open-end funds aims to address this shortcoming.)

- While most core funds are open-ended in order to provide liquidity, the ability to exit is often very limited during times of market disruption.

REITs offer superior liquidity and lower fees relative to private real estate vehicles8 and have generated similar or superior performance as private real estate over the long term.9 REITs therefore should comprise an important component of an institutional real estate portfolio, with some consideration to over- and under-weighting the sector when public and private values diverge greatly. Although long-term returns have been similar to private real estate, REITs exhibit meaningful correlation to the broader public equities market—and therefore volatility—over the short- to-medium terms. Academics and participants can (and will) argue whether this volatility reflects “true” value or not—whether the relative stability of private real assets is a bug or a feature. But for practical purposes, volatile public values can lead to wide allocation swings in the short term, which could impact decision making around acquisitions/dispositions and portfolio allocations.

In addition, neither of these approaches permits investors to take advantage of one area in which real estate can consistently add value and generate higher returns: development when there is a significant gap between property values and development costs. Development does not work well within closed end funds, and is a minor component of open end funds and REITs.

APPROPRIATE STRUCTURES

When investing in US real estate, we believe that institutional investors benefit from structures that employ the following “wish list:”

- Transparency: Property level operating performance or portfolio level attributes This allows the investor to better understand the unique risks and attributes of its properties and portfolios.

- Control of Major Decisions: Investors are able to retain the rights to major decisions when investing directly. Major decisions can include reinvestment of capital, major lease terms, financing structure and terms, hold vs sell decisions, etc.

- Leverage Optimization: Optimize the level and structure (e g fixed vs floating) of leverage.

- Alignment of Interests/Fees: Tailored investment fees that are dependent on the health of the property and incentives are aligned.

- Liquidity: The investor can determine its own investment horizon based on its unique situation.

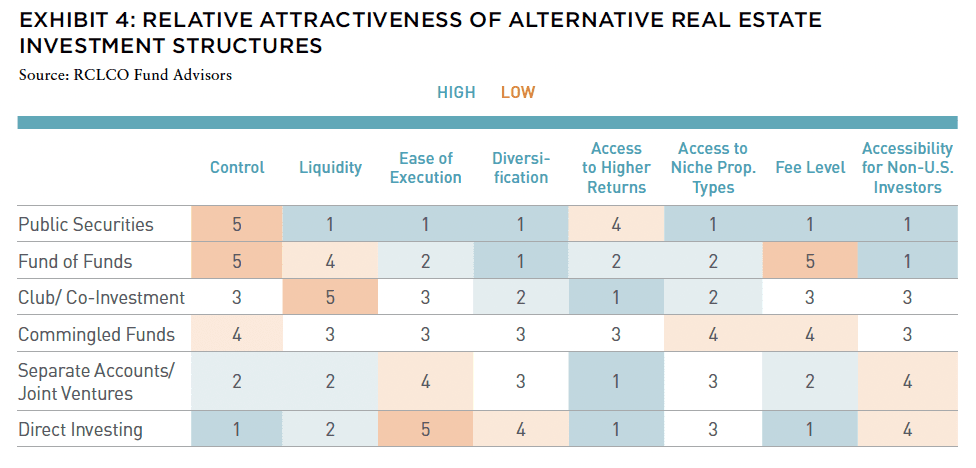

In general, achieving this wish list requires investing in more “direct” structures, such as joint ventures and separate accounts, rather than commingled funds, where nearly all control is delegated to the manager. Accessing direct structures internationally can result in greater execution difficulty, however, and utilizing local resources such as staff extension consultants, which provide on the ground intelligence and expertise, is critical. Exhibit 4 shows the range of investment structures that are available for investors to access US markets, as well as the relative advantages and disadvantages.

PARTNERING WITH OTHERS

Given limitations on direct investment by non-US entities, it makes sense to evaluate partial (less than 50%) positions in US real estate assets or ventures. Although there is generally always an interest in bringing on minority partners, many US institutions are currently facing the “denominator effect,” and have become overallocated to real estate. This has led them to seek ways to downsize their existing portfolios, such as recapitalizing a portion of their existing assets with international institutional investors.

This can be beneficial to international investors trying to invest in the US market, as it provides direct access to high quality managers and real estate, and partnering with domestic institutions can limit potential tax leakage.

DIRECT INVESTING IS A BETTER MODEL

In our view, direct ownership of private real estate addresses the inherent drawbacks of closed end funds and the limitations of open-end funds and REITs, and offers the best opportunity for investors’ real estate portfolios to meet their strategic objectives. At the same time, direct investing involves lower fees and other expenses and provides greater control over timing, leverage, property type, risk levels and other strategy decisions.

Some international (especially Canadian) and a handful of US institutional investors have embraced direct ownership, although it necessitates large internal real estate management teams. That model is difficult to implement for many non-U.S. funds, due to the high cost of establishing investment teams capable of covering the large and complex US market. For investors based outside of the US, direct ownership is best accomplished by utilizing outsourced “extension of staff” advisors and through separately managed accounts with investment managers and real estate operators. This leads to a “hybrid model” employing both internal expert resources and strategic external partners. Different regulatory and governance frameworks and internal capabilities dictate different approaches to the hybrid model.

A direct real estate program is more feasible for larger (~$1 billion in real estate NAV) institutional funds given the needs for dedicated expert resources and for diversification. However, smaller funds (or allocations to specific countries) can receive many of its advantages of direct investing through more strategic deployment of resources and capital. Focusing on forming relationships and investing with real estate operators as opposed to allocators, for example, can reduce the overall fee load and enable greater control over portfolio allocations. Securing resources (internal or external) to source and underwrite co-investments and other ad hoc opportunities can also enhance net performance.

THE PLACED OF CLOSED-END FUNDS

Despite recent findings, closed end funds are likely to have an ongoing place in institutional real estate investing. Closed end funds can provide an effective way to take advantage of a meaningful market dislocation (that is in large part how the real estate fund business got started in the RTC era of the early 1990s), address a specific strategy that entails short-term value creation, or that facilitates exploration of new markets or products before investing in the infrastructure to do so more directly. Small investors need to commingle capital in order to gain sufficient diversification, with certain attractive strategies not available in open end funds or REITs.

Recent research mandates, however, that investors (including non-US funds) and their advisors critically evaluate closed end funds’ place in their portfolios and, if necessary, make changes that generate higher net returns without commensurate increases in risk. Direct and/or hybrid approaches to real estate investment are likely important alternatives to explore.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

William Maher is Director of Strategy & Research, Taylor Mammen is CEO, and Ben Maslan is a Managing Director at RCLCO Fund Advisors.

—

NOTES

1. “2023 Institutional Real Estate Allocations Monitor,” Cornell University’s Baker Program in Real Estate and Hodes Weill & Associates.

2. Li and Riddiough, May 2023

3. Buyout fund performance stays in a “fairly tight range around the overall mean,” despite fund sizes increasing by 5 to 8 times from fund 1 to fund 7. VC funds are smaller than buyout funds and grew slowly over time, with IRRs averaging 30% for funds 6 and higher, vs. 15% for the overall average.

4. “Real Estate Returns by Strategy: Have Value-Added and Opportunistic Funds Pulled Their Weight,” Pagliari (2016), Real Estate Economics, 2016.

5. Kiehelä and Falkenbach, 2015

6. Li and Riddiough

7. Li and Riddiough (2023)

8. Arnold, Ling, Naranjo (2021)

9. PREA reports that REITs represent 62% of the Institutional U.S. Real Estate Market. Source: “Why Real Estate (Updated to Q2 2023)”.

10. Arnold, Ling, Naranjo (2021)

—