Be careful about advice you hear from surveys— it will not always play out as expected.

People do not always make decisions in a straightforward manner. In a survey they may tell you that they want to go to the gym and lose weight so that they can look like George Clooney or Brad Pitt, but then there is that donut in front of them in the here-and-now beckoning to be inhaled.

In other words, be careful about advice you hear from surveys—it will not always play out as expected.

No need to worry. I am not going to try to lecture you about response rates and arcane issues around sample sizes and probability distributions. All surveys are not the same, however, in the sense that the types of data collected and the conclusions that one can draw from them vary.

Surveys are often used to get at data points on where prices are today. The broadest index of prices in the economy comes from Consumer Price Indexes where government workers go out in the field to conduct surveys of a wide basket of goods, such as the price of pickles in Poughkeepsie or candle costs in Cleveland and a myriad of other items consumers use. These data points are rolled up to create an index that guides much thought about the credit markets globally, but at the base, these things start with a messy collection of survey responses.

Closer to home for real estate investors, surveys of market data can provide clarity as well. Before Real Capital Analytics started publishing deal-level information in 2000, investors had to rely on surveys of brokerage professionals to see how prototypical assets might price under current conditions. This approach is still valid to get a general sense of the market, but it cannot be applied to your individual building.

Surveys of current conditions have utility in that they make a simple statement about where conditions are at the moment. Stepping forward to expressions of intentions and expectations becomes a trickier business.

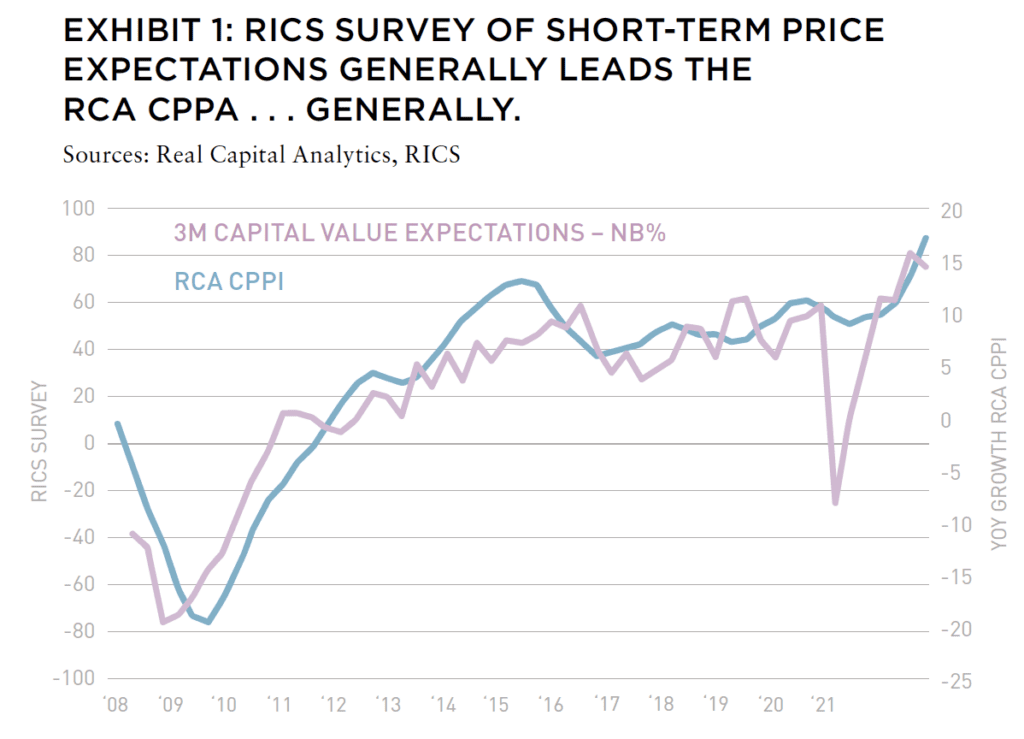

Commercial real estate markets have numerous friction points that make them predictable even without fancy econometrics over the short run. Take supply issues, for instance. If surveys show that there are no construction cranes in your city, in the near term there will be little new supply to worry about simply because of the friction of supply timelines: construction is a long process. Surveys around price expectations over the short run tend to lead the RCA CPPI as well, because it can take months for deals to close, and participants have a sense of where the chips will fall in the near future. That said, there have been some misses.

The Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) has conducted the Global Commercial Property Monitor opinion survey over many years to provide forward-looking views on market conditions. Studies have shown that changes in this survey generally lead changes in market pricing trends.1 Exhibit 1 shows the trend for the US industrial market with the expectations for changes in capital values over the subsequent three months versus the RCA CPPI. The survey clearly led the bottom of the market cycle in the aftermath of the GFC and the run up in the subsequent years.

The COVID-19 pandemic, however, seems to have caught many investors off guard. The prospect of large swaths of the economy shutting down led to fears that even the now-superheated industrial sector would experience price declines. It seems that nobody anticipated the massive fiscal and monetary responses that put a floor under price changes in 2020. With that support in place, investor expectations turned around, with prices subsequently off to the races.

The mass-emigration of millennials from large cities in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic also caught many investors off guard.2 I am not going to name and shame here, but some investment managers were out raising funds over the previous ten years with the thesis that millennials wanted to live in cities moving forward and therefore it made sense to pay higher prices for urban housing assets. This thesis was flawed because it relied on short-term desires expressed in surveys and ignored longer-term demographic issues that drive household tenure choice (i.e., rent vs. buy).

The thesis that millennials were somehow different than previous generations and that they wanted to live in cities forever seemed compelling to many. Surveys conducted in the aftermath of the GFC showed that the millennial generation preferred urban living.3 But the preferences people exhibit tend to change as they age. The preferences of people in their late 20’s and early 30’s interact well with the incentives offered in urban locations. But for people settling down and having children into their midto late 30’s and early 40’s, the incentives offered in suburban locales and smaller cities can often work better.

Surveys of expectations over the short term have some explanatory power, but investors in commercial real estate need to understand the forces driving preferences over a longer horizon. Investing in a commercial property is a long-term commitment. When underwriting a commercial real estate investment, it is important to have a structural view of the forces that drive the performance and how those forces will evolve throughout the holding period of an investment. One observation point from a survey of short-term expectations cannot paint a suitable long-term structural view of the patterns of performance.

And yet, while some investors were burned by a thesis tied to the short-term preferences revealed in surveys, many are once again responding to short-term fears over survey responses around office use. In the here-and-now, surveys are suggesting that some office workers are hesitant to return to the office. Following 9/11, similar fears were seen for office workers in the trophy towers in Manhattan and Chicago, but as the risks faded, expectations returned to where they were before the attacks.4 Investors running away from office tower investments because of short-term fears lost out on the subsequent run up in prices in the CBD offices.

Intentions are not always realized as actions. To understand future actions, one should look to economics. (What else do you expect the economist to say?) Seriously though, people respond to economic incentives. You want me to work in Dubai? You will need to offer up quite a lot to incentivize me to pick up and move there. Rank-and-file office workers are hesitant to return to the office today because there are still perceived risks, and the rewards have not stepped up enough to incentivize every worker to return.

To understand where these office workers will end up in the future, do not trust surveys of the here-and-now. Look instead to the mix of risks and rewards workers will face moving forward to determine how they will act. Surveys alone are not a problem; these can be useful tools that can guide investors. Like any tool though, they can be misused.

Sure, one could drive a nail with a socket wrench, but a hammer works much better.

—

To loosely paraphrase, reports of the death of the office are greatly exaggerated. Indeed, we are experiencing fundamental changes to the way that people work as the economy reorders itself post-COVID, but office real estate is unlikely to disappear entirely. Rather, office will evolve to accommodate new models of work and employee preferences. Other asset classes weren’t immune to pandemic disruption, either. Warehouse and housing were expected to struggle as the global economy locked down, but both soon experienced explosive growth beyond what even the most seasoned real estate practitioners predicted.

As the author rightly points out, it’s important to distinguish between short-term trends and long-term structural realignment. Compare, for example, economist Ed Glaser’s Triumph of the City, written in 2011, to his Survival of the City from 2021. Both books are thoughtful and well-researched, providing invaluable utility for understanding conditions at the moment. But the contrast in their perspective points to how difficult it is to predict a longer-term future.

Surveys report sentiment, but not necessarily actual behavior. And even if accompanied by comprehensive behavioral data, the conclusions are likely short-term and not necessarily timely. The long-term nature of real estate assets may have them drifting in and out of favor over time, making strategy decisions even harder. Technology will provide an assist, here, with artificial intelligence and deep learning used to process immense amounts of historical and realtime data, thus coming closer to predicting the future.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jim Costello is Chief Economist for MSCI Real Estate. MSCI is a leading provider of critical decision support tools and services for the global investment community.

—

NOTES

1 Andrew Kanutin, Umberto Grossp, Catarina Braga, “Opinion Survey Indicators: What Can They Tell Us About Commercial Real Estate Markets,” RICS, September 13, 2021, rics.org/globalassets/wbef-website/reports-and-research/

2 Jade Sciponi, “Millennials Have Been Moving Out of Big Cities — Here’s Where They Are Going,” CNBC.com, updated April 15, 2021, www.cnbc.com/2021/04/15/, accessed April 29, 2022.

3 Samantha Sharf, “Survey Says Millennials Want To Live In New York, Research Suggests They Should Live In Philadelphia,” Forbes.com, updated June 13, 2016, forbes.com/sites/samanthasharf/2016/06/13/, accessed April 29, 2022.

4 Norman G. Miller, Sergey Markosyan, Andrew Florance, Brad Stevenson, and Hans Op’t Veld, “The 9/11/2001 Impact on Trophy and Tall Office Property,” Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management 9, no. 2 (2003): 107–26, jstor.org/stable/24882314

EXPLORE THE FULL ISSUE (SPRING 2022)

MARCHING BACKWARDS INTO THE FUTURE

The new 2022 AFIRE International Investor Survey Report reveals future institutional investment trends as the pandemic transformed how we live, work, and play.

Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

CITIES THAT WORK

What is it that makes London, Stockholm, Berlin, Amsterdam, and Paris the top European cities for office investment? And what could this mean for other global cities?

Dr. Megan Walters | Allianz Real Estate

SURVEY SURFEIT

Be careful about advice you hear from surveys— it will not always play out as expected.

Jim Costello | MSCI Real Estate

NEW WORKING AGE

Outside of WWI and II, the US working age population has never declined. As of 2021, that statement is no longer true.

Stewart Rubin and Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

SELECTIVE FRAMEWORK

Two years after offices closed due to the COVID pandemic, the debate over the longterm future of the office continues. What should office investment look like going forward?

Dags Chen, CFA; Ryan Ma, CFA; and Ryan LaRue | Barings Real Estate

GARDEN VIEW

US garden apartment investments are offering outsized return potential –but access remains a challenge.

Martha Peyton, PhD | Aegon Asset Management

SINGLE-FAMILY DEMAND

As an increasingly popular asset class for institutional investors, single-family rentals are supported by strong future demand drivers to propel sector outperformance.

Daniel Manware | Nuveen Real Estate

ESSENTIAL HOUSING

The US is in the middle of one of the biggest housing crises that the country has ever seen. It needs a more resilient approach to housing.

Todd Williams | Grubb Properties

LODGING TAKES THE LEAD

As a labor-intensive and service oriented asset class, hospitality is uniquely positioned to be a leader in advancing sustainability goals for investors.

Charlotte Kang, Geraldine Guichardo, Lori Mabardi, and Emily Chadwick | JLL

CARRY ON, CARRY OVER

While continuation vehicles were once viewed as a signal of delay or failure, market sentiment is rapidly changing.

Max LaVictoire and Ashley Anderson | Hodes Weill & Associates

RENEWING ETHICS

A note from AFIRE’s Ethics Chair on the need for maximizing ethics in an age where globalization is under threat.

El Rosenheim | Profimex