Not all storms are the same, and some are so tragic that they force a moment of universal recalibration. Hurricane Ian was one of those storms—but what does that mean for real estate?

Climate change looms over the real estate investment community, but the industry struggles to quantify the risk to cash flow and valuations. Sometimes an event comes along, that no matter how tragic, acts as a moment of important recalibration. In the years to come, Hurricane Ian, which made its deadly landfall in Florida in summer 2022, may prove to be one of these critical events.

Climate Core Capital thinks about climate, data, and the relative risk and readiness of our cities each day. The firm watched events unfold and identified a series of observations that matter for the here and now, but also the coming investment cycle—and for future cycles that are likely to be impacted by environmental events of equal or greater ferocity.

Firstly, what was the scale of Hurricane Ian and why was its force so unprecedented?

MAGNITUDE

Ian is the thirty-seventh major hurricane (Category 3+) to strike the state of Florida since 1851 and the fifteenth to be rated Category 4 or 5 at the time it made landfall in the United States.

Ian made landfall as a hurricane three times. It first came ashore as a 125-mph Category 3 storm near La Coloma, Cuba, early on September 27, 2022. On the afternoon of September 28, the storm struck Cayo Costa, Florida, as a Category 4 with 150-mph winds. Two days later, Ian made its final landfall near Georgetown, South Carolina, as a Category 1 at 85 mph.

Rising ocean water piled up onshore—up to twelve feet in some places. A record-breaking storm surge of more than seven feet entered parts of Fort Myers, Florida, at nearly twice the height of the previous record set by Hurricane Gabriel in 2001. Fourteen inches of rain in twelve hours is considered a one-in-a-thousand-year event in this corridor of southwestern Florida. Southern Sarasota County exceeded fourteen inches in twelve hours, and some reports suggested as much as twenty inches in some locations. Ninety-two people lost their lives in the United States as a result of the storm, and most of the reported deaths were drownings in Florida.

Around 2.7 million customers were in the dark at peak outage in Florida. That adds up to about 25% of the state, markedly higher than for Category 5 Hurricane Michael, which left 4% of the state without power in 2018. North Carolina recorded around 350,000 people without power at its peak, and South Carolina had around 218,000. Virginia topped 100,000. Georgia added about 15,000 out at peak.

Ian’s web of damage was unusually widespread as the hurricane drove storm surge onto coastal areas and triggered river overflows and flash flooding across inland Florida, where almost nobody expects water stress, and subsequently, has no flood insurance.

CONTEXT

At 150 mph, Ian’s landfall wind speed in Florida ties for the fifth strongest on record in the United States, a mark shared by seven other storms. It ties for the fourth-highest landfall speed on record in Florida. The storm made landfall very close to where Charley (2004) did when it also struck with 150 mph winds.

The yearly precipitation averaged over the whole Earth is about 39 inches (100 cm), but this is distributed very unevenly. Nevertheless, more than a third of our planet’s annual rainfall fell in Southwest Florida in just half a day.

Previously, storms tended to weaken as they neared the northern Gulf Coast due to cooler waters or stronger jet stream winds. But that did not happen with Hurricanes Michael (2018), Laura (2020), Ida (2021) or Ian (2022). A disturbing trend is emerging.

HISTORICAL TREND

With thirteen named storms as of November 1, 2022, the Atlantic hurricane season in 2022 actually ran below the year-to-date ten-year average (sixteen named storms) and most recent thirty-year climatology (thirteen; 1991–2020).

What are we to make of this last fact? It leads some to conclude tropical storm patterns remain in a somewhat consistent band, and there will continue to be hurricane seasons of varying severity. This misunderstands two key points. Firstly, even if the simple number of hurricanes remains constant, their intensity and speed of formation are increasing in an alarming direction. Secondly, and most crucially, more people, households, and businesses have moved in ever greater numbers into the path of exposure.

For the way we currently approach urban design, no city can cope with its average annual rainfall falling in half a day— and that’s without considering the impacts of storm surge bringing more water into coastal areas from the sea. It’s important to appreciate the wider context of what major population centers will contend with as they face more intense and frequent hazards.

The second point is arguably even more critical for real estate investors to acknowledge: the frequency of “the Big One” in the market where you own real estate is not so important if the financial system is recognizing the risk more accurately. Why? Because repricing always follows risk recognition.

THE PRICE OF SUNSHINE

Ian struck the state of Florida during a very precarious time for the state’s insurance market. Recent rating agency reviews of numerous insurance carriers’ ability to maintain viable business operations in Florida had already put a strain on the overall market, and media reporting has indicated half a dozen bankruptcies in 2022 even prior to Ian.

This has resulted in a rapid rise in the number of active policies in Florida’s state-run Citizens Insurance program, which is considered to be the carrier of “last resort” for residential and commercial entities. According to Climatewire, the number of its policyholders has doubled in the past two years and recently passed one million for the first time since 2014.1 The average property insurance rate in Florida is $4,231—nearly triple the US average of $1,544, according to the Insurance Institute. At what point do workers, businesses, or retirees decide this is an operational expense that outweighs the quality of life?

Behind each natural disaster is a financial market that needs to reprice, reevaluate, and rebalance. The practical side of this, however, is not easy. Markets (and investors) continue to back thirty-year mortgages and long-duration municipal bonds in locations like coastal Florida with no climate risk premium. More than 7.2 million single and multifamily residences were in Ian’s path with high flash flood risk, according to risk analytics fi rm CoreLogic.2 But the mortgages, insurance products and bonds supporting these locations are securitized into enormously deep pools with geographic diversity across the whole country. Up until this point, the theory has persisted that the US can withstand a few billion-dollar disasters, given our scale of liquidity—but how long will this be the case?

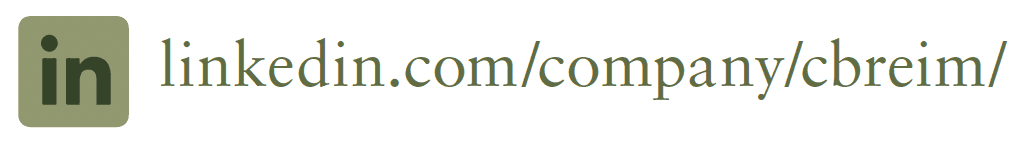

The problem is the frequency of disaster risk is only moving in one direction (credit: NOAA).

“THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS A NATURAL DISASTER”

Modern natural disasters occur at the intersection of natural events and human decisions. Ian is a story with many narratives, but one such narrative is that of a high-end hurricane making landfall near a metropolitan area that constructed more than four hundred miles of shallow canals at the wide mouth of a river as a habitat for 760,000 people.

It’s also important to remember many of Hurricane Andrew’s (1992) legacies. One of these is that South Florida became home to some of the best building code requirements in the US. Another is that Andrew effectively bankrupted the Florida insurance industry and led insurers to develop sophisticated catastrophe modelling to better price their risk exposure. We cannot rule out similar market disruption, long-run risk innovation, and “new normal” market dynamics brought on in the wake of Ian.

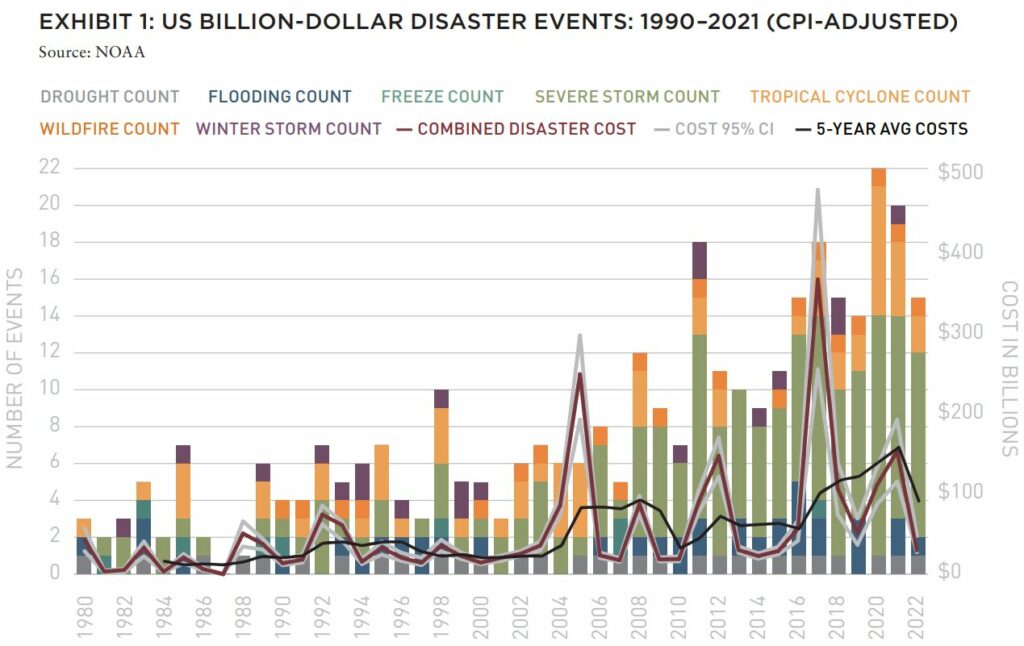

We all need to think deeply on the extent to which American communities in high-risk corridors can cope with intergenerational risk exposure. The map below (credit: Steve Bowen) provides an updated look at current National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) take-up as of 31 August 2022.

With storm surge having caused devastating impacts in Charlotte, Lee, and Collier counties, it’s worth reflecting on how much of this disruption will be uninsured—either because of the risk calculus of an individual homeowner, or pricing, or a poorly designed system that doesn’t sufficiently protect those who do participate.

Climate change does not discriminate. The broader reality we continue to drive as a firm is that information is not equally shared, incentives are not aligned, and the financial system is presently unable to recognize the risk accurately. The repricing is underway in localized settings, even if large investment products overlook the delta.

PREPARING FOR FUTURE STORMS

What does all this mean for large institutional investors, many of whom could be asking any of the following questions:

- If I have followed the Sunbelt thesis of the last fifteen years and allocated into higher climate risk markets, what is the right way to think about rebalancing or divestment?

- In the markets where I invest, will public and private stakeholders coordinate toward resilience?

- Do investment time horizons align with my risk appetite?

- Should climate change frame my underwriting and perception on equity, debt, and the capital stack?

- How do I stay informed and engaged on evolving climate risks, and in what ways can I “in-house” the expertise?

As Margaret Atwood famously said: “It’s not climate change, it’s everything change.” Financial and capital markets will decide if Hurricane Ian is a moment of recalibration and the beginning of a new approach to a pervasive risk across future market cycles. It’s time to ask: Am I being adequately compensated for my risk?

EXPLORE THE LATEST ISSUE

MAKE SUSTAINABILITY REAL

With the case for sustainability already well-established, how can (and should) real estate continue to lead?

Gunnar Branson | AFIRE

RETURN GENERATION POTENTIAL

In addition to offering inflation protection and lower volatility, real estate also offers something that other asset classes can’t: the opportunity to invest in tangible, positive change.

Shane Taylor | CBRE Investment Management

CATCH A FALLING *R

The future path of long-term interest rates in the US and why it matters.

Alexis Crow, PhD | PwC

TIDAL PATTERNS

Amidst myriad global economic and geopolitical uncertainties, US commercial real estate has an even greater challenge ahead: demographics.

Martha S. Peyton and Caitlin Ritter | Aegon Asset Management

WORKPLACE VALUES

The sooner we can recognize that values have come down collectively—even beyond the office sector—the sooner we can move forward to capitalizing on new opportunities.

Dags Chen, CFA | Barings Real Estate

OFFICE GAMES

Even as the US office sector has lagged other property types, there could be an important (and valuable) difference of office performance based on property age and market.

William Maher and Scot Bommarito | RCLCO

EMISSION CRITICAL

Workers spending less time in the office post-pandemic may seem negative for the office sector, but a four-day workweek can be a boon for some office property owners.

Kevin Fagan, Xiaodi Li, and Natalie Ambrosio Preudhomme | Moody’s

MOVING TARGETS

A close-in look at twenty major US metros and thousands of properties shows how the overall impact of rising expense loads have narrowed NOI margins. Investors should take note.

Gleb Nechayev, CRE and Webster Hughes, PhD | Berkshire Residential Investments

SAND STATES

In the wake of the Great FinancialCrisis, certain metros in the Sand States suffered disproportionally. It may not be as bad this time.

Stewart Rubin and Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

STORM WARNING

Not all storms are the same, and some are so tragic that they force a moment of universal recalibration. Hurricane Ian was one of those storms—but what does that mean for real estate?

Rajeev Ranade and Owen Woolcock | Climate Core Capital

PACIFIC THEATER

The Asia-Pacific region is already home to some of the world’s largest economies and now set to lead global economic growth. What’s moving the needle now for the APAC region?

Simon Treacy and Yu Jin Ow | CapitaLand Investment

STABLE SPACE

For e-commerce property investors, the past decade was outstanding, but even as market dynamics are slowing industrial’s momentum, market fundamentals remain sound.

Mehta Randhawa | JLL

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Rajeev Ranade and Owen Woolcock are Partners at Climate Core Capital, a real estate and alternative investment management firm focused on climate change and climate risk funds.

—

NOTES

1. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/10/10/ian-cracks-floridians-nest-eggs-00060759

—

REVIEWER RESPONSE

At a time when demographic patterns in many parts of the world involve movement of people and businesses toward locations vulnerable to climate-related disasters, Rajeer Ranade and Owen Woolcock of Climate Core Capital are asking real estate investors many pertinent questions. These include whether climate risk is priced into the cash flow assumptions on which properties are being underwritten as well as the valuation metrics being applied to these cash flows. They have an appropriate focus on insurance, wondering whether a shift in the cost and availability of insurance in markets like Florida, prone to both wind and flood, has been factored into operating cost assumptions.

Ranade and Owen posit that Hurricane Ian, which hit the Gulf Coast of Florida and South Carolina in September and is expected to be one of the costliest catastrophes in US history, may represent a tipping point for real estate investors. Will this storm prompt investors to ask a series of what if questions about the value of their holdings? What if Ian causes a reversal in migration trends, causing a decline in the labor pool available to support an office investment or in the size of the trade area for an apartment or a retail asset? What if property taxes double, triple, quadruple as local governments rebuild infrastructure to reflect the reality of wind, storm surge and inundation? What if capital market demand goes negative?

In light of the rapid escalation in the number of extreme weather events, in their magnitude, and the speed at which they occur, the authors suggest that investors ask themselves whether it is time to divest from locations that may represent more risk than they underwrote. We concur, suggesting that investors set their risk tolerance and use this to guide portfolio construction.

Mary Ludgin, PhD

Head of Global Investment Research, Heitman

Member, Summit Journal Editorial Board

THIS ISSUE OF SUMMIT JOURNAL IS PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY

Our focus on delivering results is driven by our values, entrepreneurial spirit and our clients’ diverse needs. Together, our team specializes in holistic real assets solutions within and across five real assets investment categories, with a distinct approach to driving performance and long-term value.

CBRE Investment Management is a leading global real assets investment management firm with $143.9 billion in assets under management as of September 30, 2022, operating in more than 30 offices and 20 countries around the world. Through its investor-operator culture, the firm seeks to deliver sustainable investment solutions across real assets categories, geographies, risk profiles and execution formats so that its clients, people and communities thrive.

CBRE Investment Management is an independently operated affiliate of CBRE Group, Inc. (NYSE:CBRE), the world’s largest commercial real estate services and investment firm (based on 2021 revenue). CBRE has more than 105,000 employees (excluding Turner & Townsend employees) serving clients in more than 100 countries. CBRE Investment Management harnesses CBRE’s data and market insights, investment sourcing and other resources for the benefit of its clients. For more information, please visit cbreim.com.