Multifamily properties with “good bones” often offer strong upside potential through renovation, rehabilitation, rebranding, and repositioning.

Thirty years ago, US multifamily housing experienced a remarkable period of transformation. At that time in the 1990’s, architects and developers targeted for improvement many of the characteristics that had previously relegated rental housing to second tier status relative to homeownership. Sound attenuation got better. Enhancements to community safety were incorporated. Energy conservation became a consideration. Nine-foot ceiling heights and higher became the standard. Clubhouse design and the range of onsite amenities saw dramatic improvement.

The base product became so much better that a high percentage of the communities built after 1990 share many critical characteristics with properties that developers are delivering today. But the older 1990’s and 2000’s properties have aged, generally rent for less than the new product, and have fallen a step behind in terms of interior design, amenities, and energy conservation. Properties with “good bones” nevertheless often offer strong upside potential through renovation, rehabilitation, rebranding, and repositioning.

The following shares best practices on revitalizing multifamily communities. The typical goal is to improve the selected property to (1) compete at a level slightly below brand-new communities and (2) to extend the effective life of the property. With focus, patience, and effective property management during the renovation process, experience indicates very significant upside risk-adjusted return potential.

BACKGROUND ON MULTIFAMILY

In 2019, research by Bond, Shilling and Wurtzebach found that capital improvements lead to higher incomes.1 While not fully capitalized into market values, investors are fully compensated in terms of total return. They suggest that capital improvements are defensive and may outperform investment made in boom times. Additionally, Gosh and Petrova (2017), found that all forms of capital expenditures have a persistently strong relationship with cumulative returns.2

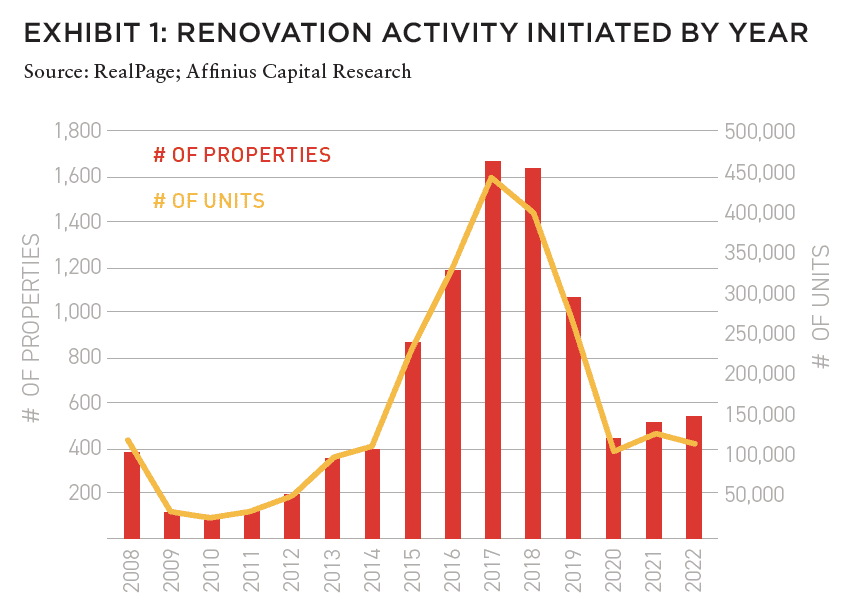

Based on RealPage Axiometric data since 2008, renovation activity peaked in 2017–18 and has been more muted since the pandemic. Nineteen percent of all properties in the Axiometric apartment database have been renovated over the past fifteen years (Exhibit 1).

THE RENOVATION OPPORTUNITY

For investors, the key questions to answer are of course (1) are the relative returns offered by multifamily renovation attractive? And (2) is there a large enough opportunity to capitalize. To address the latter, we examine recent renovation activity. Since 2008, across the major US multifamily markets, RealPage has captured a large sample of renovation activity; 9,566 building renovations, comprising almost two-and-a-half million units.

Exhibit 1 provides a detailed breakdown of these renovation activities by the year they commenced. Of note, just under 20% of all properties in the RealPage property database were renovated during this expansive 15-year period, which highlights the magnitude of the opportunity.

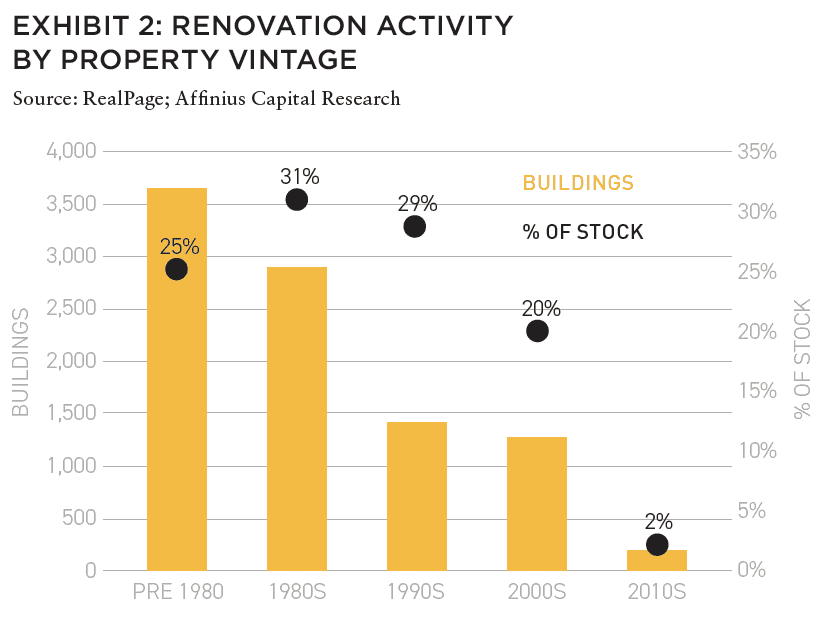

As discussed, the vast majority of the renovation activity took place on product that was older. Exhibit 2 shows a breakout of renovated buildings by vintage; over 84% of all activity took place in buildings built before the 2000s, and 28% of the pre-2000 stock was renovated in the past fifteen years. However, there remains a large portion of the older stock will likely require upgrades in the future to remain competitive and attract tenants, and it is likely that the post-2000 stock will also require increased attention to keep pace with amenities and tenant requirements.

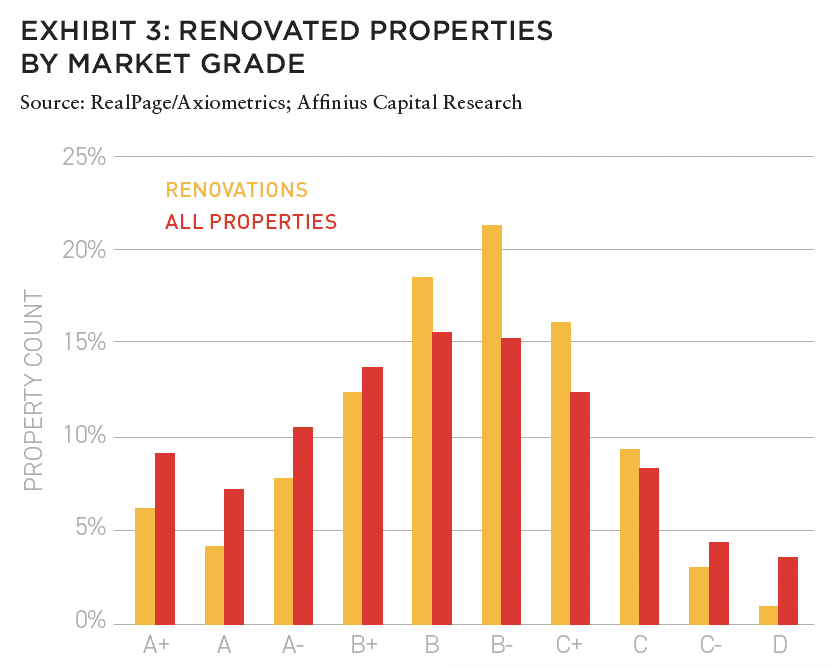

It is no surprise that renovations disproportionately occurred in Class B, B-, and C+ graded assets, as shown in Exhibit 3. These properties are likely strong candidates as they are not competing purely on affordability, as are perhaps assets lower in class, but have aspirations to move closer to Class A assets and increase rents. That said, it might surprise some readers the extent to which the renovation activity is occurring across all product types, even at the top of the market. This suggests assets of all sizes and vintages can benefit from capital expenditures, or at least require them to keep pace with the market.

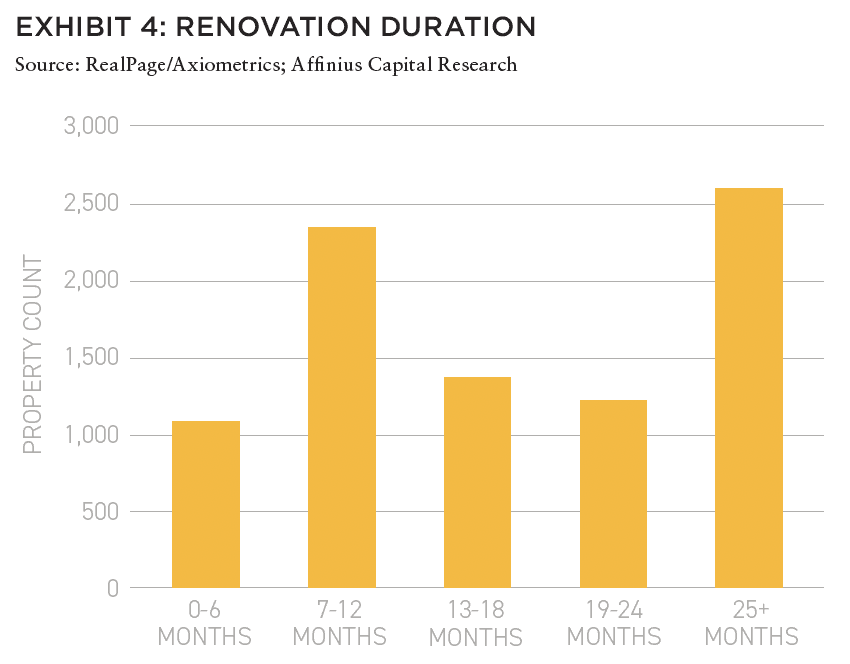

Important to note is that the extent of building renovation varies widely. In some cases the changes may be more cosmetic, such as installing new countertops and stainless-steel appliances; in other situations a more substantial overhaul of amenities, shared public spaces, and even unit configurations may be required, and these can take longer and require more downtime for the units. Exhibit 4 shows the distribution of renovation times for projects that have completed their renovation since 2008.

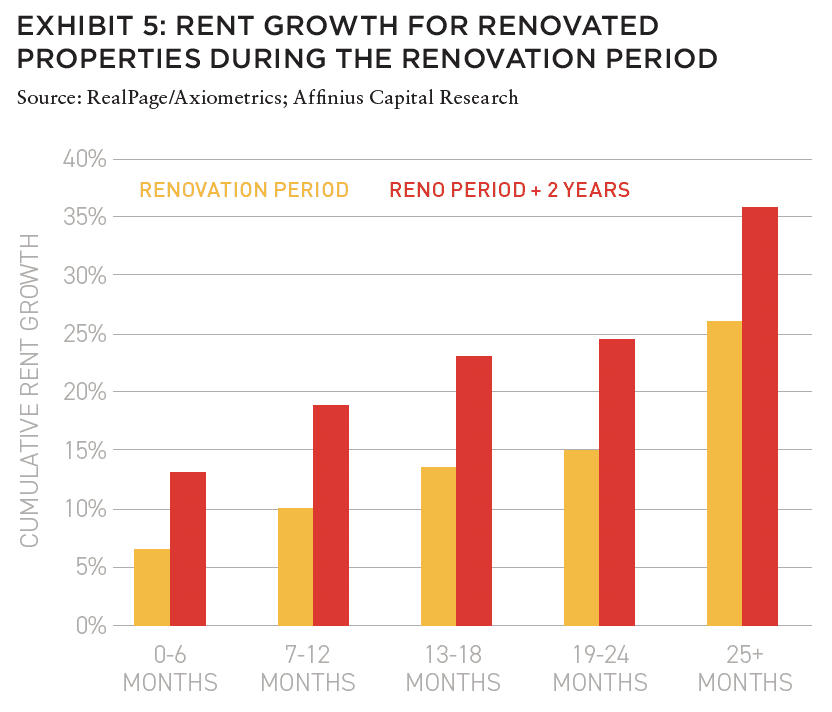

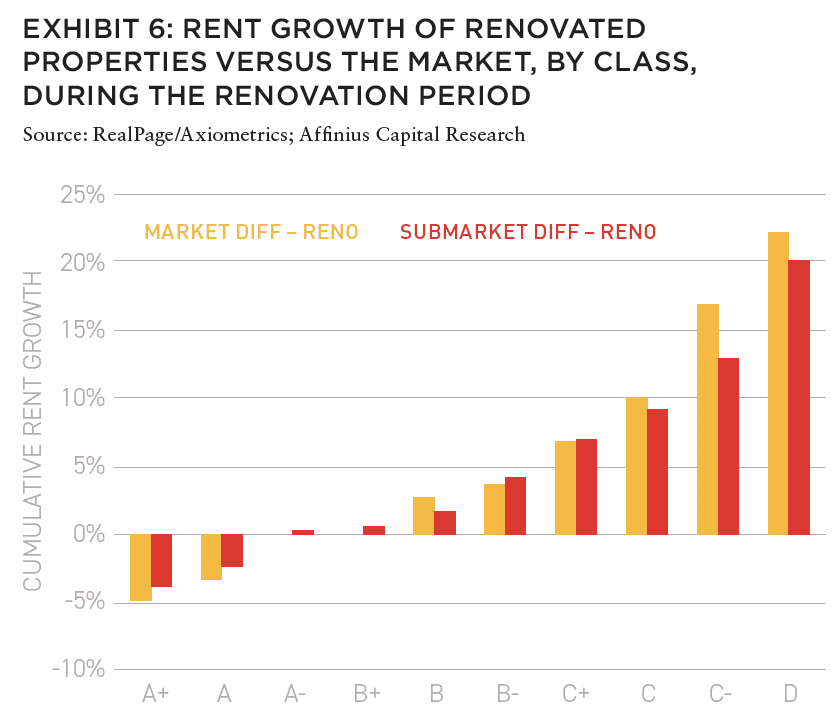

Exhibits 5 and 6 focus on the ability of owners to drive rent growth at renovated properties. As shown in Exhibit 5, over the fifteen-year horizon, rent growth in during the renovation period has been strong, and the more substantial the renovation, the higher rents are able to be raised. We also capture the post-renovation period, two years after completion of the renovation, as this may be where some additional rent growth can be captured as the market realizes the increased competitiveness and quality of the asset.

A more robust comparison of the relative success of a rehabilitation project would account for market rent growth during the timeframe. For example, if a renovated property saw rents increase 15%, but the overall market rents increased 20% during the period, an investor might be less inclined to consider the investment a success relative to if overall market rents had stayed flat. In Exhibit 6, we break out the renovations by quality of the property, and compare rent growth during the renovation period relative to overall market rent growth. The results suggest that lower quality assets see more rent growth when renovated relative to the market. This might be explained by a few factors:

- Lower-quality assets have more to gain from a renovation

- Class A renovations may be more targeted to keep pace with their peers, and/or be the result of a repair or other incident

Overall, these data suggest the opportunity is sizable, and finding the right assets can dramatically alter the financials.

TARGETS

A primary underlying consideration in acquiring properties to redo is location. As the population has continued to grow and infill sites have become harder to find and much more expensive to acquire, the underlying value of the land on which many communities were built in the 1990’s and 2000’s has increased significantly. The popularity of infill locations among renters has only soared. A compelling location typically provides older communities with a strong competitive advantage even versus newer properties. A great location offers a compelling starting point for a renovation program.

Physical condition is another consideration. Properties of the vintage under discussion exhibit a wide range of deferred maintenance and capital expenditure exposures. An interesting way of thinking about these issues is to segregate improvement activities into two categories – defensive and offensive.

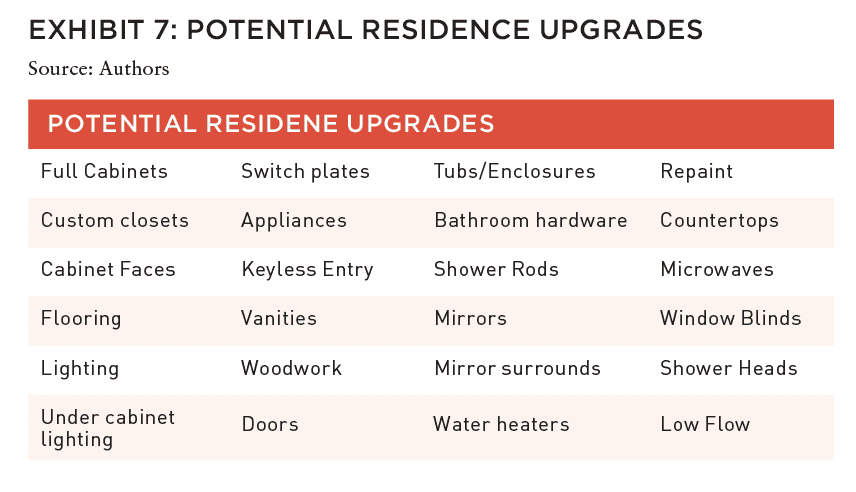

Generally, defensive improvements are those for which ownership cannot typically generate immediate additional revenue. For example, residents do not generally pay up for new roofs although they may improve the overall aesthetic appeal of the property. Similarly, tenants generally do not pay up for new or revitalized stairway systems. In most instances, though, to realize the property’s maximum upside potential, the full range of building systems—roofs, stairs, gutters, windows, HVAC, water heaters—often must be addressed. While not a certainty, payback for addressing deferred maintenance and deferred capital expenditures occurs through realization of a lower residual cap rate. Otherwise, renovations and rehabs focus on offensive activities—those which really attract the attention of potential residents and for which they are willing to pay up. These activities are the ones which most in the industry think of in terms of renovation and include unit upgrades, clubhouse, and amenity improvements and, potentially, added density.

Where ginning additional rent is the name of the game in this part of the program, an experienced renovator will add renovation features until—at the margin—the last added feature delivers upside potential that just meets a hypothetical return on investment threshold. This calculation is more of an art than a science. Nevertheless, the idea is to add elements to the renovation until the overall return on investment slips to a certain target level.

For example, ownership may be able to upcharge by $100 per month or $1,200 per annum on a custom closet installation with a cost of $1,000, while up charging just $5 per month or $60 per year on an installation cost of $500 for hardwired under-cabinet lighting. Experienced renovators constantly assess what renters are seeking and willing to pay more for in their apartment homes, clubhouses and amenity offerings and they deliver accordingly.

When planning a community renovation, ownership assesses the ratio of defensive to offensive activities. While defensive upgrades are almost always part of the equation, obviously, a property with lower deferred maintenance and capital expenditure exposure is preferable; however, often to unlock a property’s full upside potential, some defensive work must be undertaken.

In targeting high potential opportunities, acquirers also consider several aspects of property management. Assessing the performance of the incumbent firm is a starting point. A less than optimal performance provides additional upside potential; however, attributing the current level of performance to the team in place versus other shortfalls specifically attributable to the property requires considerable skill and intensive analysis. Other considerations include real estate tax exposure and management, insurance cost and coverage, payroll sufficiency, and overall maintenance.

IN THIS ISSUE

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR: WELCOME TO #13

Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

OFFICE TROUBLES: FINANCIAL RISKS AND INVESTING OPPORTUNITIES IN US CRE

Dr Alexis Crow | PwC + Byron Carlock

THE UNDERPERFORMANCE PARADOX: WHY INDIVIDUAL INVESTORS FALL BEHIND DESPITE BUYING LOW

Ron Bekkerman | Cherre + Donal Ward | Tenney 101

CLIMATE THREAT: EXTREME WEATHER IS THE NEW NORMAL FOR REAL ESTATE

Jacques Gordon, PhD | MIT

CLIMATE OPPORTUNITY AWAITS: HOW REAL ESTATE CAN INVEST IN CLIMATE ADAPTATION

Michael Ferrari, PhD and Parag Khanna, PhD | Climate Alpha

PREMIUM PRICE TAGS: INSURABILITY THROUGH PROPERTY RESILIENCE DATA

Bob Geiger | Partner Engineering & Science

REAL ESTATE WEB3: THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES OR THE NEXT BIG THING?

Zhengzheng Tan, Alice Guo, and Naveem Arunachalam | MIT

ADAPTIVE TO REUSE: COULD BUILDING CONVERSIONS BE DIFFICULT, EXPENSIVE . . . AND STILL PROFITABLE?

Josh Benaim | Aria

RENOVATE, REBRAND, REPOSITION: ADDING VALUE TO MULTIFAMILY THROUGH REVITALIZATION

Robert Kilroy, CFA | The Dermot Company + Will McIntosh, PhD | Affinius Capital

REDEFINING THE PROGRAM: A CONVERSATION WITH ARCHITECT DAVID THEODORE

Peter Grey-Wolf | Wealthcap + David Theodore | McGill University

SENIOR HOUSING UPDATE: EMERGING OPPORTUNITIES THROUGH DEMOGRAPHIC TAILWINDS AND DIMINISHING SUPPLY OUTLOOK

Robb Chapin, Jack Robinson, Andrew Ahmadi, and Morgan Zollinger | Bridge Investment Group

SENIOR HOUSING UPDATE: UNPRECEDENTED DEMOGRAPHIC ACCELERATION MAY DRIVE STRONG OPERATING FUNDAMENTALS AMID ECONOMIC SLOWDOWN

Tom Errath | Harrison Street

HOLIDAY FROM HISTORY: REASONS FOR US OPTIMISM IN A CHANGING GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT

Charlie Smith | Newmark

CRADLE TO CRADLE: AN ALLOCATOR’S VIEW ON IMPLEMENTING ESG INITIATIVES

Christopher Muoio and Katie Cappola | Madison International Realty

FREE LUNCH: MULTI-DIMENSIONAL DIVERSIFICATION IS A FULL-COURSE FREE MEAL

Elchanan Rosenheim and Tali Hadari | Profimex

CAMPAIGN MESSAGING: CFIUS, AFIDA, AND EXPANDING FEDERAL AND STATE RESTRICTIONS ON FOREIGN INVESTMENT IN US REAL ESTATE

Caren Street, John Thoms, and Anya Ram | Squire Patton Boggs

PURCHASING THE PROPERTY

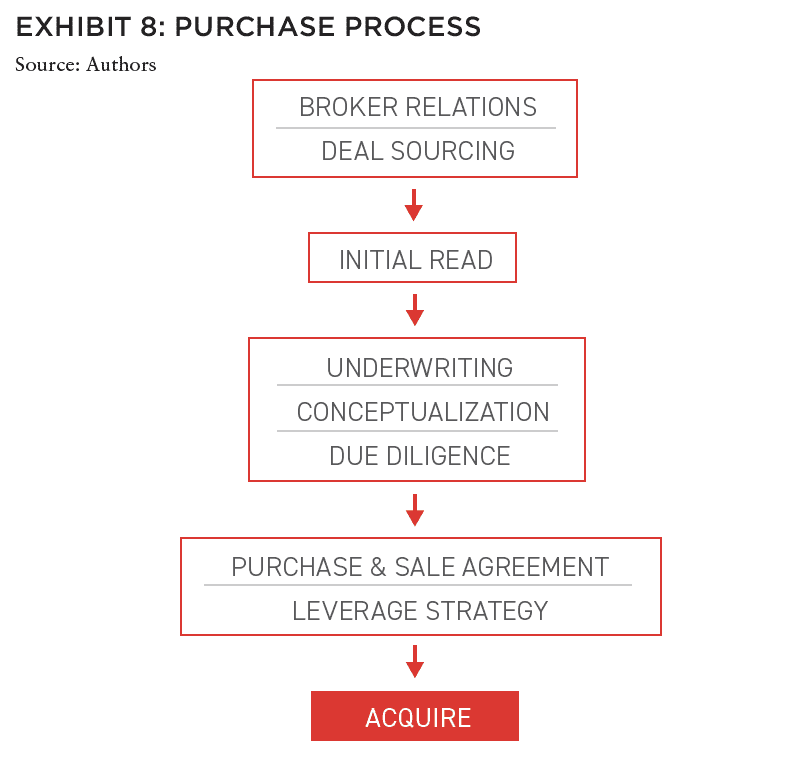

The renovation, rehabilitation, repositioning process starts upon first inspection of the property. Acquisitions officers perform the standard analyses and immediately start to hypothesize about: (a) what can physically and effectively be accomplished; (b) how much it will cost; (c) the activities’ upside potential; and (d) how long the activities will take.

Exhibit 8: Purchase Process

Source: Authors

Given ever-shortening due diligence timeframes, developing an early on cost-benefit analysis in very short order is critical. The insights of property managers, interior designers, architects, landscape architects, contractors, and suppliers are important. Strong past relations with all potential participants in the renovation process is necessary. Their participation and insight make a lot of difference in determining the ROI of the contemplated improvements. Even with their input, inflation and supply chain disruptions can have a dramatic impact upon the eventual outcome. Analysis should include a large cost overrun contingency.

Theprocess of analyzing the market and designing an overall post-renovation product that offers a reasonable price-value proposition is exacting. It entails developing a clear understanding of pricing at different levels of quality. Often, the strategy will be to deliver a living experience that is almost equal to but just slightly below that of the high-priced competitors.

During due diligence it is important to assess the potential of the existing resident base to pay up for the better product. A resident base that is stretching to pay current levels of rent is unlikely to renew at the higher rent payment levels needed to justify the renovation. Re-tenanting the property is not out of the question in most instances, though it does require a higher vacancy reserve during the renovation.

Leverage strategy also plays an important role in the purchase decision. While generally beyond the scope of this paper, how the property is leveraged and potentially re-leveraged can dramatically alter the risk profile of the renovation. An important part of the equation is how ownership will fund the renovation. Funding with equity is obviously the least risky means: the tradeoff is the lower returns implicit in de-leveraging.

Post-closing, the renovation process kicks into gear. Often ownership will set aside a period of six months or more to: (a) gain a complete understanding of property operations; (b) assess the resident base; and (c) plan the renovation program.

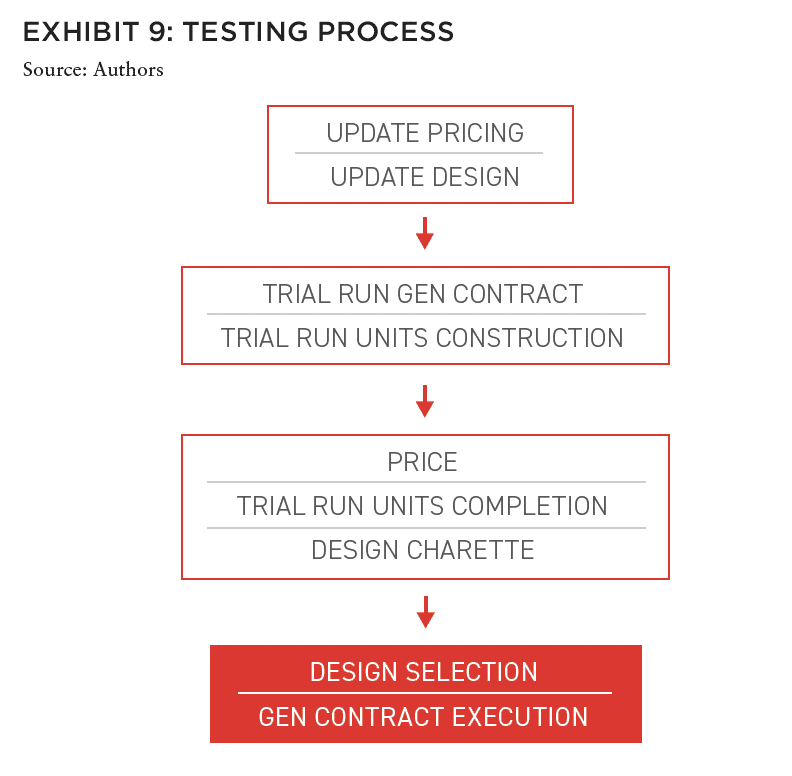

A primary risk-limiting approach is to “trial run” the unit renovation program. This consistently includes the design three or more level of finishes across a variety of unit types to assess: (a) market receptivity of the product; and (b) pricing (rental upside) potential. Performing a trial run is informative and risk limiting. The feedback gained from the exercise is very helpful in setting the broader strategy. Design charettes—with the participation of ownership, investors, consultants, and vendors—are useful in determining the final unit designs.

Implicit in this analysis are two considerations worthy of further discussion.

First, we outline a “go-first” approach with the unit renovation program. Often this is preferable as unit rents show the community’s upside potential. Alternatively, proceeding, first, with a clubhouse renovation is certainly an option, but it’s a bit trickier assessing the bottom-line impact of this approach and while the unit renovation program is alterable, major projects such as a clubhouse redo offer less flexibility.

Second, the approach outlined above assumes that the residences are captured for renovation as residents terminate their leases. Another means of renovating uses a building-by-building approach.

Buildings are de-leased and delivered to the general contractor without any residents living in the apartments. The primary benefit of this approach is that it shortens the overall renovation timeframe. The main drawback is that it is very difficult and often costly to capture all the units in each building simultaneously.

With lessons learned from the trial run and design charette, ownership can make a go/no go decision on the broader program.

The owner may have a captive general contractor that executes the physical renovation. More often, however, ownership will contract with a third–party general contractor and proceed with the renovation under a guaranteed maximum price contract. Pricing is agreed to in advance at a fixed price subject to change orders. A frequently used contract is the AIA 101 form of contract tailored to meet the specific circumstances: It is typically paired with AIA 201 form that details the general conditions of the contract.

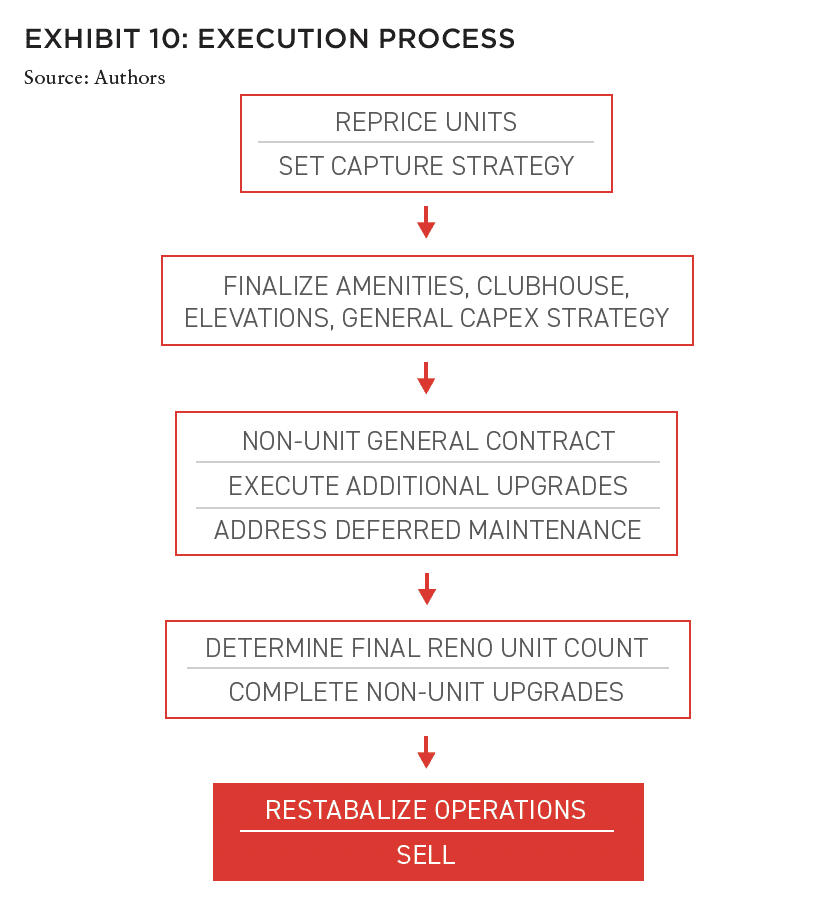

Ownership then needs to decide how wide a range of activities the contract or contracts will cover. One general contract may cover the full range of renovation activities or different contractors may perform different aspects of the work. Further, the owner may direct contract for parts of the renovation and may perform renovation work themselves if fully integrated.

Even under the one contract approach, ownership may have superior purchasing power and may contract directly with major supply houses such as Ferguson, Lowe’s or HD Supply for all or parts of the renovation. Taking the materials component out of the general contract can lead to solid cost savings. How involved ownership is in the purchase process and self-performance varies widely depending on ownership’s staffing levels and expertise.

Flexibility of contracting provides a significant benefit in terms of risk and reward. While experience suggests that the actual return to the renovation activity is highly consistent with (and often significantly exceeds) initial expectations, circumstances can necessitate substantially altering the renovation.

The strategy for each community differs in terms of scope and units involved. One approach has ownership completing a set number of residence renovations leaving a percentage for the next owner to complete. Alternatively, and especially when longer-term ownership is likely, the typical intent is to renovate all the apartments. When this is the case, it is important to structure the general contract to provide for an acceleration, deceleration, or termination of the program as circumstances warrant.

Professionally managing the resident base is an important key to achieving success with the renovation. Depending on the level of renovation, the sounds and activities of the renovation team can be problematic for the residents. Experienced property management can smooth this over. Also, while the range of upcharges will vary, selling the increases is often challenging especially at the higher end of renovation.

With heavier unit renovation programs where the accelerated timing of turning the renovations apartments is critical, capturing units to turn is important and often this means non-renewing residents – intensively toward the end of the process. The resident’s disappointment at not being allowed to renew his or her lease is often mitigated by offering the displaced resident a newly renovated apartment with incentives such as free rent or a moving allowance.

Careful analysis of the pre-buy rent roll is important in determining the overall strategy. If the average in-place resident is already stressed to meet rent payments, a re-tenanting of the property is likely with significant vacancy implications.

Minimizing vacancy during renovation enhances the bottom line. Quick contractor turns and effective property management limits the downtime. Standard practice requires residents to provide 2-months’ advance notice for renewal or departure. Assuming a larger community of, say, 300 residences, a retention ratio of 50%, and a target maximum number of units under renovation of fifteen at any one time, the supply of units for renovation is typically fine for the first twelve to fifteen months. Throughout the term of the unit renovation program, rent pricing remains critical and provides a useful feedback loop. Initially, ownership sets rent premium expectations and each renovated apartment provides an important feedback loop datapoint that, in turn, can lead to plan modifications. Assuming the unit renovation program is achieving the desired level of premiums and returns on cost, ownership can then consider proceeding with the other components of the renovation: the clubhouse, amenities, defensive work, and rebranding. The clubhouse deserves special consideration.

CLUBHOUSES AND AMENITIES

The potential residents’ initial overall impression of the community is largely a product of what they find when they enter the property’s clubhouse. We believe the upside potential of a substantial clubhouse upgrade is often overlooked. In some instances, a complete demolition of the facility could be warranted. Often, leaving the base building and adding on to it can work. In many regards, clubhouse renovations parallel the unit renovation program; however, an important consideration is to program the improvements to augment the overall community appeal.

Clubhouses come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes based on the original development team’s budget and hypothesis as to the role of the clubhouse in leasing and resident retention. Best practices include a thorough re-evaluation of the clubhouse and community amenities based on experience and the intensity of the unit redesign. Architects, engineers, and interior designers are important participants.

ENERGY EFFICIENCY/GREE/ESG

Addressing the carbon footprint of communities is a dramatically emerging trend in renovations. Until recently, the primary challenge with “greening” communities has been that the associated activities have been costly and due primarily to the direct billing of residents, it has been challenging for owners to realize a return on investment.

This ROI challenge is now changing. The first and still emerging approach that facilitates an ownership financial return is through lender-provided green loan incentives. Overly simplified, the lender provides the loan on a reduced interest rate basis – in return ownership agrees to complete energy conserving property improvements. The list of qualifying improvements is significant and includes HVAC, water heaters, low flow toilets, faucets, and showerheads, window replacement, improved insulation, and solar, among several others.

HVAC replacement is the most promising energy conserving activity. Due to governments’ ban on the production of Freon, the dwindling supply and increasing cost of refurbished Freon, and the increasing cost of maintaining older equipment, HVAC systems upgrades provide a moderate cost approach to improving communities’ carbon footprints.

Again, it is difficult for ownership to immediately monetize a return to performing the improvements – other than through loan incentives; however, the likelihood of a buyer paying more for a property that has performed one or more of the capital upgrades is very high and can impact the operational and financial performance.

REBRANDING

Rebranding is often an important component of the process and will likely include signage replacement, a new website, and updated collateral leasing materials. The more intensive the renovation, the more likely a new “look” will help unlock leasing potential. Third-party designers, sign manufacturers, printers, and website designers all oversee parts of the upgrade.

SUCCESS

What does success with a multifamily renovation look like? The key metric is generating higher rents while keeping a lid on operating costs. This drives NOI. In addition, effective execution of the previously noted “defensive” activities should result in a lower residual cap rate than would be the case without the CapEx program.

A typical underwriting term for value-add is five years. Assuming a 300-unit community and a target average renovation term of fifteen units per month, the renovation, including a six-month planning cycle, will take 26 months. Often it will take two turn cycles to realize the full upside potential of the renovation to realize the targeted return. The length of time for a full upside realization is often lengthened when the renovation is comprehensive, including potentially, clubhouse, elevation, landscape, and amenity improvements. With re-stabilization of the rent roll proving the value of the renovation, owners typically underwrite with an expected hold period of five years.

Assuming a standard 3% per annum market rental rate tail wind, renovation premiums that deliver a combined 12% ROI, and an initial cap rate of 4.5% to 5%, a base line expectation is, that post-renovation, the current return on cost will increase into the 6% to 6.5% range, and this will drive the 5-year XIRR up into the 14% to 17% range in the current climate. Note, also, that the level of “defensive” capex activities may significantly impact the final XIRR.

—

REVIEWER RESPONSE

The authors expertly lay out a comprehensive framework for understanding US multi-family renovation projects including many of the considerations that should be taken to enjoy the expected returns. Even for groups not embarking on directly with the work, this article can serve as a roadmap to help select a partner particularly for foreign investors who may not be as familiar with the American multi-family model.

The article suggests that it is possible that a template formula that can be applied anywhere in the US. There is no discussion of regional differences, or if a successful team in one part of the country can fully exploit their expertise elsewhere. Should a successful team stick to their region or is it possible to export their best practices and be profitable elsewhere in the country?

Further exploration could focus on the authors’ observations about how remote work trends are changing the demands for the types of renovations that are more successful, in location, geography, product, or even services. Does the rise of hybrid work create entirely new opportunities? The article briefly touches upon property management without elaborating on the service aspect of project. Could enhancing or altering the scope of services increase rents with minimal capital expenditure?

Lastly, it would be helpful to consider if any jurisdictions in the US have regulations surrounding the process of “de-leasing”. Even if there are no legal rent controls, do any jurisdictions regulate “de-leasing”? Other parts of the world can be very tenant friendly about this part of the process. In the absence of bylaws or regulations what are the best practices that could maximize reputational benefits (or at least minimize risks) in this regard?

– Peter Grey-Wolf

Vice President, Wealthcap

Member, Summit Journal Editorial Board

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Will McIntosh, PhD, is Global Head of Research, for Affinius Capital, which invests across the risk spectrum and capital stack for a global client base, managing a diverse portfolio of real assets across North America and Europe. Robert Kilroy, CFA, is a partner with the Dermot Company, a fully-integrated real estate enterprise with over 20 years of experience and $3.5 billion+ assets under management.

—

NOTES

1. Bond, Shaun, James D. Shilling, and Charles Wurtzebach, Commercial Real Estate Market Property Level Capital Expenditures: An Options Analysis, Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, Vol. 59, No. 3, 2019.

2. Petrova, Milena and Chinmoy Ghosh, The Impact of Capital Expenditures on Property Performance in Commercial Real Estate, Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, Vol. 55, No. 1, 2017.

—

THIS ISSUE OF SUMMIT JOURNAL IS PROUDLY UNDERWRITTEN BY

For more than 20 years, Yardi has developed real estate investment management software that helps managers of global assets valued at trillions of dollars make informed investment decisions. Yardi Investment Suite clients include many of the world’s premier investment management funds, start-ups and partnerships of all types and sizes.

Real estate investments grow on Yardi. That’s because the Yardi Investment Suite automates complex investment management processes and provides full transparency, from the investor to the asset. Through interactive dashboards, investors can view documents and have access to reports and metrics. Collaboration is easy when your advisor or accountant is given access to view your accounts, reducing the need for emailing sensitive information.

The Yardi Investment Suite leads the real estate industry through innovation and value with fully integrated investment management, property management and accounting functionality. Fund managers and their customers can manage assets with superior efficiency and ease. Learn more.