The commercial real estate industry may not yet fully grasp the actual relationship between climate risk and asset pricing and value. But the knowledge is coming fast.

Many institutional real estate investors have significant exposure to cities and regions that are economically important but increasingly susceptible to climate change impacts. Climate change is becoming one of the most important structural forces and risks that long-term investors need to proactively consider in building resilient portfolios. While climate events are not new, there is growing evidence that the frequency, intensity, and geographic spread of climate events have increased in recent decades and this dynamic coincides with the emergence of more chronic events including temperature and sea level rise.

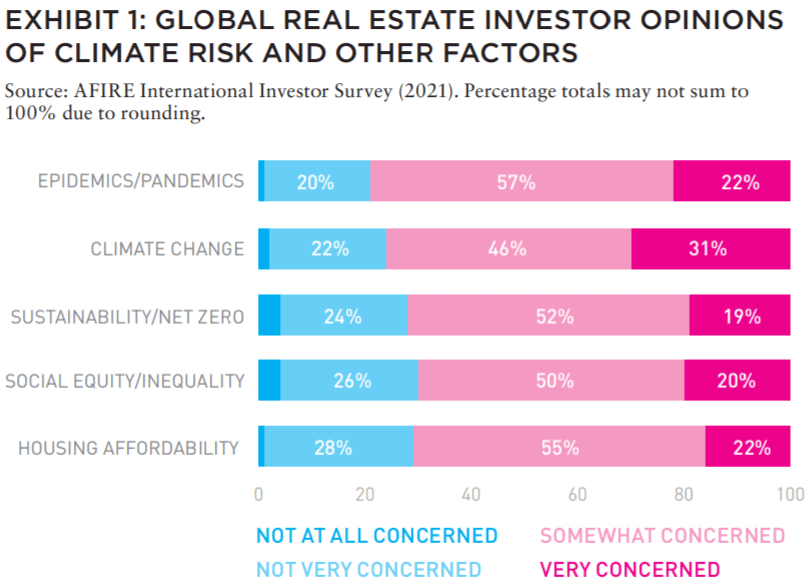

People continue to adapt in creative ways. When AFIRE members were surveyed in March 2021 for the Exhibit 1 provides recent survey evidence that illustrates industry awareness and concern amongst AFIRE members. Almost 80% of responses to AFIRE’s annual investor survey indicated that they are either “concerned” or “very concerned” about climate risks. The existence of climate risk does not necessarily mean that investors should avoid or withdraw from those places, but a reassessment of risks, allocations, and potential mitigation actions is important to protect or limit impacts on performance.

Recent industry commentary and analysis reveals the challenges associated with incorporating complex risk considerations into valuation and investment processes and decisions. The Urban Land Institute (ULI) in conjunction with real estate investment management firm Heitman lays out many of the issues and explore current industry practice in surveys of industry participants.1 These reports, consistent with the AFIRE survey, find significant investor awareness.

In going a step further to assess if awareness has led to action, the studies conclude that the industry is in the early stages of incorporating heightened climate risk into the investment and valuation process. Many investors are beginning to work with one or more of the growing rosters of forward-looking climate risk assessment firms to incorporate climate risk into investment and asset management decisions. However, connecting the perceived risk to valuation and pricing is more tenuous.

A major impediment to a rigorous forward-looking assessment of the financial impacts of climate risks on asset values is lack of knowledge and empirical evidence about how property markets have responded to past extreme weather events and how they are responding today to more chronic forces such as sea level rise.

To help fill the gap and investigate this, a team of researchers from University of Reading (UK) and York University (Canada) worked to collate and assess the existing empirical evidence for the extent and channels through which real estate values and prices have responded to recent extreme weather events.2 If climate change risks are in fact already recognized by market participants, then their impact should be observable through pricing behavior at purchase/sale or in OpEx/CapEx decisions. They analyzed mainly recently published studies of pricing and investment behavior following extreme weather events for evidence of such impacts. The research revealed a fairly thin and inconclusive empirical evidence base and suggests that the industry has not yet come to grips with quantifying the relationship between physical climate risk and pricing and value.

Insurance, building design and location choices, codes and standards, government infrastructure investment, and governance capacity all contribute to resilience and can support asset values, and there is some evidence that that climate risk is partially capitalized in values. But even if this is the case, this level of risk absorption may be insufficient against the increased projected severity of acute and chronic climatic effects and likelihood of compounding physical and economic harm. It is imperative then to assess the extent to which markets are, or are not, appropriately pricing physical climate risk now and to understand more about the basis against which forward-looking modelling and analyses (services for which are widely available) are being made.3

SHORT-TERM VERSUS LONG-TERM ADJUSTMENT DYNAMICS

There is ample evidence that prices drop after acute climate events, but, generally, the drop is modest and short-lived. This has been shown in residential markets,4 and more recently in commercial markets.5 These studies and others assessed markets where major storms were more common. This could imply that the threat is realized and that the risks are already capitalized into property prices, but a short-term, myopic approach to investor/owner value and pricing cannot be ruled out.

Some recent research suggests a softening of this dynamic, although this is limited to analyses following Superstorm Sandy. There may even be a permanent post-event price discount which appears to apply to properties directly affected by Sandy, properties that were unaffected directly but within the storm affected area, and potentially coastal properties in other markets not directly affected by Sandy but exposed to similar events.6 This last instance may be a case of “belief updating” where risk information is becoming more available and better internalized within individuals and institutions and markets are adjusting accordingly.7

LIQUIDITY RISK CONSIDERATIONS

Immediately following climate events, acute market impacts may be assumed; that is, fewer listings and sales and/or lower prices for assets that do sell. Pricing tends to be a lagging or post-hoc indicator of how markets are absorbing physical climate risk so trading volumes or time on market may be better leading indicators. Prices, sale volumes, and velocity should be studied to fully capture the market’s response.8 The availability and cost of lender financing and re-financing, as well as insurance, are likely key determinants of investor behavior and liquidity in areas historically subject to climate events, and importantly for areas generally unexposed in the past but subject to shifting patterns and conditions (including chronic factors such as sea level rise).

Concerns around climate change, affordable housing, and economic and social inequity also saw slight increases in concern, though concerns about Research focused on Florida residential markets has looked at prices and volumes for areas exposed to sea level rise and has found that sale volumes declined in more exposed areas relative to less exposed areas even while prices held generally steady (at least until recently). The authors suggested this was driven by a change in buyer demand, as there was, at that time, no evidence for a shift in the practices or availability of insurers/insurance and lenders/credit.9

MORTGAGE LENDING AND SECURITIZATION

There has been a lack of academic research on the impact of severe weather events on real estate debt markets and no published academic research that has focused on commercial mortgage markets. Yet credit rating and mortgage analytic firms all have significantly increased their physical climate risk-related analyses of and focus on the mortgage sector, especially in US mortgage-backed securities (MBS) markets, and the municipal finance and infrastructure areas that could ultimately impact property pricing in higher risk locations.

There is evidence, though, that US residential lenders are becoming more aware of risks that could ripple through to default rates and that they are using this information for decisions on which loans to retain versus those sold to government-sponsored enterprises (e.g., Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) for securitization. These findings pertain to both post-storm behavior as well as areas considered to be at risk from sea level rise.10

ASSET LEVEL RISK MITIGATION

Insurance clearly supports investor returns and the ability to lend against assets. Obvious risks to both arise if insurance becomes unobtainable, or even if terms such as exclusions, higher excesses and/or significant changes to premiums are seen. There is little evidence yet from the literature that this has been seen. And in fact, the US National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) may be creating moral hazard and propping up prices11—though proposed changes to the NFIP may offer a case study once information accumulates as most policy holders are expected to see an increase in rates.

For commercial real estate, insurance issues may influence occupier behavior and thus feed into owner cash flow considerations.12 Owners can improve resilience through actions to ‘harden’ assets against extreme weather and there is anecdotal evidence that some owners and managers are making ‘defensive’ capex decisions to remain aligned with market expectations. This decision-making is complicated by the fact that many climate risks may not yet be properly reflected in CRE market values, so the benefits from mitigation expenditure might not be fully recognized either. To date, insurers have not incentivized resilience expenditure through premium discounts or other market influencing actions.13

IMPLICATIONS FOR ASSET VALUING AND MODELLING

Understanding how property values could be materially affected by the physical impacts of climate change is of paramount importance to investors.14 However, the overall picture from the published literature shows a growing but incomplete evidence base. Using geospatial data to highlight potential risk from asset exposure to acute and chronic climatic events is a meaningful first step and one that many institutions have only just begun to take. But clearly more nuanced and actionable information will be needed.

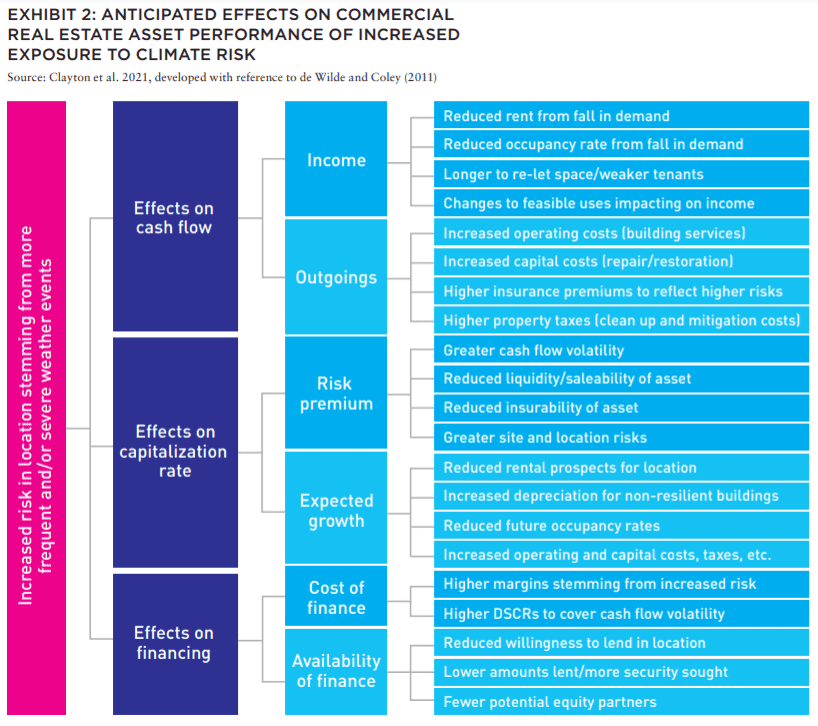

To help conceptualize this, Exhibit 2 shows potential financial materiality of climate risk on commercial real estate assets. It demonstrates how climate change physical risks could feed through to income-property pricing in a discounted cash flow (DCF) appraisal framework. These risks could be incorporated in valuations through an impact on three primary components: (1) cash flow—leasing fundamentals (rent, rental growth, and vacancy) net of operating expenses and capital expenditures; (2) capitalization rate—affected by capital market conditions including the overall required return that embeds the required risk premium, plus expectations of cash flow prospects (including exit price) and liquidity; and (3) financing—the cost and availability of funds from both equity partners and mortgage debt finance are directly related to return requirements and indirectly to property liquidity.

Most studies to date have analyzed prices, but not the channels through which prices are determined. There is also a lack of clarity on how different market setters and actors evaluate climate risks and influence investor calculations.

Providers of insurance and debt have their own perspectives on climate risk that may impact on pricing of their products, partly driven by their decision timeframes. Investor hold periods may be 8–10 years, and secured lending agreements range from 3–7 years, while insurance premiums are priced annually. This creates cash flow and financing risks which may later exert downward pressure on prices where physical climate risks are identified or found to be increasing post-acquisition. Similarly, it is unclear on how occupiers will respond to climate events and risks; and advisors and valuers may lack uniform knowledge, instruction in professional standards on climate risk, and access to data which may impact value. Lastly, government regulations for and investments in resilience plausibly contributes to investor confidence, but how much this affects values and prices is imprecise.

But at the same time, the calculus for diverse talent development, recruitment, and retention is related to (and informed by) the same eIPPC research makes clear that physical climate change is no longer a factor that any real estate investor can ignore. Greater knowledge and more granular data sets are required to discern factors that protect investment values and returns, but also to inform a debate about how to protect or manage stock which lacks climate resilience. The UNEP FI sponsored research15 on which this article is based concludes with recommendations for industry and academe to collaboratively engage on data sharing, financial and valuation modelling practices, asset and area resilience investment planning, and CRE focused research. Outputs from such activities can improve the information flow and evidence base for decision-making and help refine valuation and investment allocation practices with emerging risk factors and their inherent uncertainties.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE (FALL 2021)

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR / GROUPTHINK VS. GROUP COLLABORATION

AFIRE | Benjamin van Loon

MID-YEAR SURVEY / CHECKING THE PULSE

No matter your age or experience, 2021 has shaped up to be a year that no one can forget. Findings from the AFIRE 2021 Mid-Year Pulse Survey detail a cautious road ahead.

AFIRE | Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon

CLIMATE CHANGE / REASSESSING CLIMATE RISK

The commercial real estate industry may not yet fully grasp the actual relationship between climate risk and asset pricing and value. But the knowledge is coming fast.

York University | Jim Clayton

University of Reading | Steven Devaney and Jorn Van de Wetering

Kinston University | Sarah Sayce

UNEP FI | Matthew Ulterino

NON-TRADITIONAL / THE ALLURE OF SPECIALTY SECTORS

Real estate investments have historically coalesced around common property types—but it may make sense for investors to reconsider specialty property sectors in the post-COVID world.

Invesco Real Estate | David Wertheim

NON-TRADITIONAL / NON-TRADITIONAL IS GOING MAINSTREAM

The mainstreaming of nontraditional property types is well on its way within institutional investing, which will materially broaden the real estate investment universe.

Principal Real Estate Investors | Indraneel Karlekar, PhD

DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE / DIVERSIFYING INTO DIGITAL

As investors look for sustainable sources of inflation-protected yield, real estate investment is increasingly blurring into a wider range of “digital” real asset investment strategies.

AECOM Capital | Warren Wachsberger, Josh Katzin, and Corbett Kruse

LIFE SCIENCES / TAPPING INTO BIOTECH

Over the past two decades, the single-family rental industry haLife sciences real estate has been a “hot” property type for the past decade—and even more since the pandemic. Will all the capital targeting the space be placed where it needs to go?

RCLCO | William Maher, Ben Maslan, and Cecilia Galliani

ESG + CLIMATE CHANGE / HIGH-WATER MARKS

Interest and excellence in ESG performance is becoming increasingly critical to portfolio strategy. So with sea levels on the rise, how can portfolios stay above water?

Barings Real Estate | Jerry Speltz

ESG + NET-ZERO / VALUING NET-ZERO

With more tenants focusing on environmental targets, the burden to reduce direct emissions places increased pressure on investors, who are at a pivotal moment in ESG strategy.

JLL | Lori Mabardi, Emily Chadwick, and Eric Enloe

ESG + FAMILY OFFICE / FAMILY OFFICES AND ESG

As sustainable investing continues to grow in popularity, family offices have taken note—and understanding ESG targets and regulations will be key for longterm performance.

Squire Patton Boggs | Kate Pennartz and Rebekah Singh

DEBT / WHY DEBT, WHY NOW?

Debt funds remain a comparatively small part of the real estate investment market, but they have been gaining in prominence in recent years.

USAA Real Estate | Karen Martinus, Mark Fitzgerald, CFA, and Will McIntosh, PhD

MIGRATION / MIGRATION IN REAL TIME

As the public health situation started to improve in early 2021 and the economy reopened, did migration flows change too—and what if we are able to answer this in real time?

Berkshire Residential Investments | Gleb Nechayev

StratoDem Analytics | Michael Clawar

URBANISM / DOWNTOWN DISRUPTION

The pandemic-driven changes to downtown areas and central business districts is changing the geography of institutional investment. What else changes because of this?

Drexel University | Bruce Katz

FBT Project Finance Advisors + Right2Win Cities | Frances Kern Mennone

WORK-FROM-HOME / CHOOSING FLEXIBILITY

Employees are increasingly demanding flexibility and choice for where (and when) they work. What strategies can landlords implement to adapt?

Union Investment Real Estate | Tal Peri

TALENT AND RECRUITMENT / TALENT PARITY

To be better prepared for future risks, firms need diverse talent. So is the goal of 50% female representation achievable in global real estate investment and asset management firms?

Sheffield Haworth | Isabel Ruiz

CLIMATE CHANGE / PREDICTING THE CLIMATE FUTURE

We are all invested in the cities, assets, and infrastructure of tomorrow, even if we might not live to see the ten largest cities in 2100. But understanding climate change can get us closer.

Climate Core Capital | Rajeev Ranade and Owen Woolcock

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jim Clayton is professor, the Timothy R. Price Chair and the director of the Brookfield Centre of Real Estate and Infrastructure at the Schulich School of Business, York University, Toronto, ON Canada; Steven Devaney is associate professor and research division lead in real estate and planning at the Henley Business School at the University of Reading, UK; Sarah Sayce is professor of sustainable real estate at the Henley Business School, University of Reading, UK and Emeritus Professor, Kingston University, UK; Matthew Ulterino is Responsible Property Investment program manager at UNEP FI; Jorn Van de Wetering is associate professor in sustainable real estate and director of studies for real estate & planning at the Henley Business School, University of Reading, UK.

—

NOTES

1 ULI, Heitman, Climate Risk and Real Estate Investment Decision-Making, Urban Land Institute, February 5, 2019, https://www.heitman.com/news/climate-risk-andreal-estate-investment-decision-making/ULI, Heitman, Climate Risk and Real Estate: Emerging Practices for Market Assessment, Urban Land Institute, October 5, 2020, https://knowledge.uli.org/en/Reports/Research%20Reports/2020/Climate%20 Risk%20Markets.

2 Jim Clayton, Steven Devaney, Sarah Sayce, and Jorn Van de Wetering, Climate Risk and Commercial Property Values: A Review and Analysis of the Literature, UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative, August 17, 2021, https://www.unepfi.org/publications/investment-publications/climate-risk-and-commercial-property-values/.

3 Paul Smith, The Climate Risk Landscape: Mapping Climate-related Financial Risk Assessment Methodologies, UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative, February 17, 2021, https://www.unepfi.org/publications/banking-publications/theclimate-risk-landscape/

4 Below, Scott, Eli Beracha, and Hilla Skiba. “The Impact of Hurricanes on the Selling Price of Coastal Residential Real Estate.” Journal of Housing Research 26, no. 2 (2017): 157–78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26393441; Norm G. Miller, Jeremy Gabe, and Michael Sklarz, “The Impact of Waterfront Location on Residential Home Values Considering Flood Risks,” Journal of Sustainable Real Estate 11, no. 1 (2019): 84-107, https://doi.org/10.22300/1949-8276.11.1.84.

5 Jeffrey D. Fisher and Sara R. Rutledge, “The Impact of Hurricanes on the Value of Commercial Real Estate,” Business Economics 56, no. 3 (March 2021): 129-145, https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-021-00212-9.

6 Francesca Ortega and Süleyman Taspinar, “Rising Sea Levels and Sinking Property Values: Hurricane Sandy and New York’s Housing Market,” Journal of Urban Economics 106 (July 2018): 81-100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.06.005; Jawad M. Addoum, Piet M. A. Eichholtz, Eva Maria Steiner, and Erkan Yönder, “Climate Change and Commercial Real Estate: Evidence from Hurricane Sandy,” MCRE, March 17 2021, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3206257.

7 Asaf Bernstein, Matthew Gustafson, and Ryan Lewis, “Disaster on the Horizon: The Price Effect of Sea Level Rise,” Journal of Financial Economics 134, no. 2 (November 2019): 253-272, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.03.013

8 Geoffrey K. Turnball, Velma Zahirovic-Herbert, and Chris Mothorpe, “Flooding and Liquidity on the Bayou: The Capitalization of Flood Risk into House Value and Ease-OfSale,” Real Estate Economics 41, no. 1 (February 2013): 103-129, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1540-6229.

9 Benjamin J. Keys and Philip Mulder, “Neglected No More: Housing Markets, Mortgage Lending, and Sea Level Rise,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series (October 2020), http://www.doi.org/10.3386/w27930; Jesse M. Keenan and Jacob T. Bradt, “Underwaterwriting: From Theory to Empiricism in Regional Mortgage Markets in the US, Climatic Change 162 (June 2020): 2043-2067, https://doi. org/10.1007/s10584-020-02734-1.

10 Jesse M. Keenan and Jacob T. Bradt, “Underwaterwriting: From Theory to Empiricism in Regional Mortgage Markets in the US.”; Amine Ouazad and Matthew E. Kahn, “Mortgage Finance and Climate Change: Securitization Dynamics in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series (September 2019), http://www.doi.org/10.3386/w26322

11 Norm G. Miller, Jeremy Gabe, and Michael Sklarz, “The Impact of Waterfront Location on Residential Home Values Considering Flood Risks.”

12 Gaye Pottinger and Anca Tanton, “Flooding and UK Commercial Property Investment: What is the Risk?” Qualitative Research in Financial Markets 6, no. 2 (July 2014): 211-226, https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-10-2012-0029; Abdullah Alzahrani, Halim Boussabaine, and Khalid Almarri, “Emerging Financial Risks from Climate Changes on Building Assets in the UK,” Facilities 36, no. 9 (August 2018): 460-475, https://doi.org/10.1108/F-05-2017-0054

13 Jessica Elizabeth Lamond, Namrata Bhattacharya-Mis, Faith Ka Shun Chan, Heidi Kreibach, Burrell Montz, David G. Proverbs, Sara Wilkinson, “Flood Risk Insurance, Mitigation and Commercial Property Valuation,” Property Management 37, no. 4 (April 2019): 512-528, https://doi.org/10.1108/PM-11-2018-0058; Hannah Teicher, “Practices and Pitfalls of Competitive Resilience: Urban Adaptation as Real Estate Firms Turn Climate Risk to Competitive Advantage,” Urban Climate 25 (September 2018): 9-21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2018.04.008

14 The terms “price” and “value” are being used rather loosely and somewhat interchangeably. However, it is important to distinguish between a valuation, a transaction price, and an assessment of investor worth. A valuation is the opinion by an expert as to a likely sales price, normally based on an analysis of past transactions; it is therefore essentially a backward-looking measure, although it should include a forward look based on an evidenced likelihood of future changes in market sentiments. Price, on the other hand, is what is achieved from sales in the market and, particularly in a residential context, may not have been influenced by professional valuations or advice unless borrowing was required. Finally, an investor’s appraisal of worth is based on a forward projection of the likely income flows, capital appreciation and risks over a defined holding period. Clayton, Devaney, Sayce and Van der Wetering (2021) examine the role of valuations and valuation standards in an international context as they apply to climate risk considerations, as well as review the academic literature on the impact of climate risk on valuations.

15 Jim Clayton, Steven Devaney, Sarah Sayce, and Jorn Van de Wetering, Climate Risk and Commercial Property Values: A Review and Analysis of the Literature.