As the public health situation started to improve in early 2021 and the economy re-opened, did migration flows change too—and what if we are able to answer this in real time?

Migration was a key differentiator in the US housing market performance through 2020 and into 2021, both across and within markets. As the pandemic spread, people moved from more densely populated and more expensive gateway metro areas to more affordable ones, as well as from cities to suburbs. Residential demand responded quickly to the changing patterns and 2020 ended with an unusually wide variation in rent growth and home price appreciation around the country.

As the public health situation started to improve in early 2021 and the economy reopened, did migration flows change too? Are migration patterns responding to the recent increases in the Delta variant infections?

The following analysis, which is based on mobile phone data, sheds light on these questions and provides early evidence that, for the most part, population losses or gains (depending on location) directly triggered by the pandemic are likely temporary. We also find that mobile phone data can be a good predictor of near term domestic net migration in general, and therefore a key alternative source relative to the official estimates that are provided by the US Census Bureau, which has at least a one-year lag.

These new data allow us to track domestic migration flows in real time, and also offers a few important additional advantages, including the ability to conduct analysis at the most granular levels of geography, as well as by various demographic characteristics, such as household income or age.

DATA VALIDATION

Using mobile phone data to track migration is still an emerging area of research. There is no shortage of firms that now offer a wide range of products and services based on such data to help their customers answer all kinds of questions that have to do with locational attributes. Not surprisingly, it is a particularly hot topic in proptech that is transforming real estate, including how firms search for and analyze potential opportunities for investment and development.

While it makes sense that technology would make it possible to track people’s daily mobility through their mobile phone usage, we could not find any published studies or articles on how accurately this can be done–at least relative to publicly verifiable US sources. This prompted us to do our own analysis and the results turned out to be quite encouraging.

One of the first steps in the analysis was to compare our implied domestic migration estimates based on mobile phone data to the actual domestic migration estimates provided by the US Census Bureau across states, metro areas, counties, and cities.1

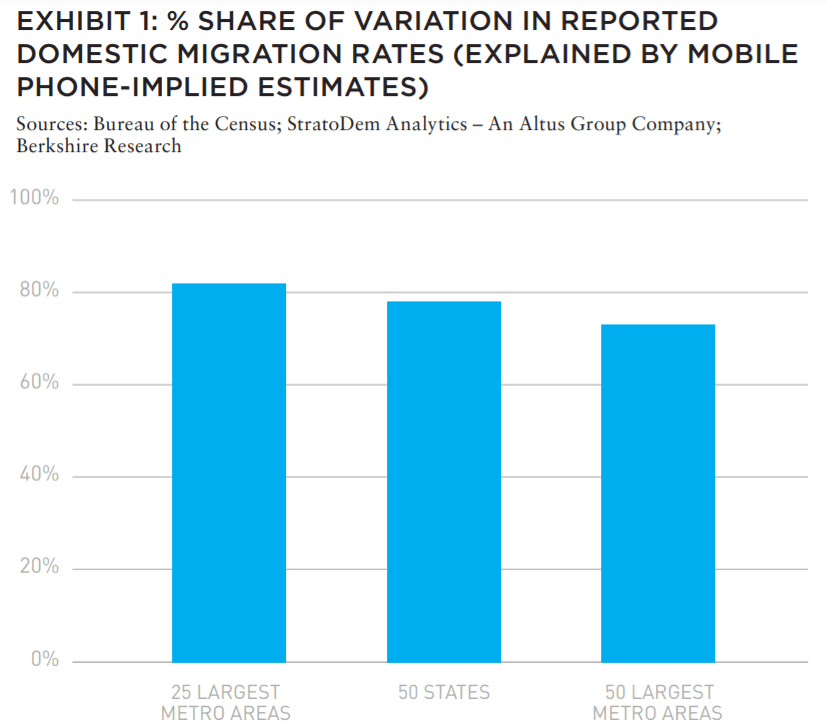

Once we confirmed that the two sets of estimates are highly correlated across various geographies, the next step was to determine whether our estimates of domestic migration in the current year could also be reliably used as a predictor of the official domestic migration figures reported by the census in the following year. We found that they could, especially in more populous parts of the country where large mobile phone data sets provide more representative samples (Exhibit 1). Of course, it helps that domestic migration patterns change gradually from year to year, but it was important to prove that the new alternative source of high-frequency (monthly) data can be used as an accurate leading indicator for the main driver of population growth across markets.

DOMESTIC MIGRATION DURING THE PANDEMIC

Once the data was validated, we were much more confident answering two key questions that arose in 2020 as the pandemic started regarding major impacts on domestic migration trends:

1) Are people moving out of the more expensive and more densely populated metro areas—especially coastal and gateway markets—and, if so, are they moving out at greater rates than in the prior year?

2) Are people moving out of major cities into suburbs more than they did in the prior year, or are they leaving for other metro areas?

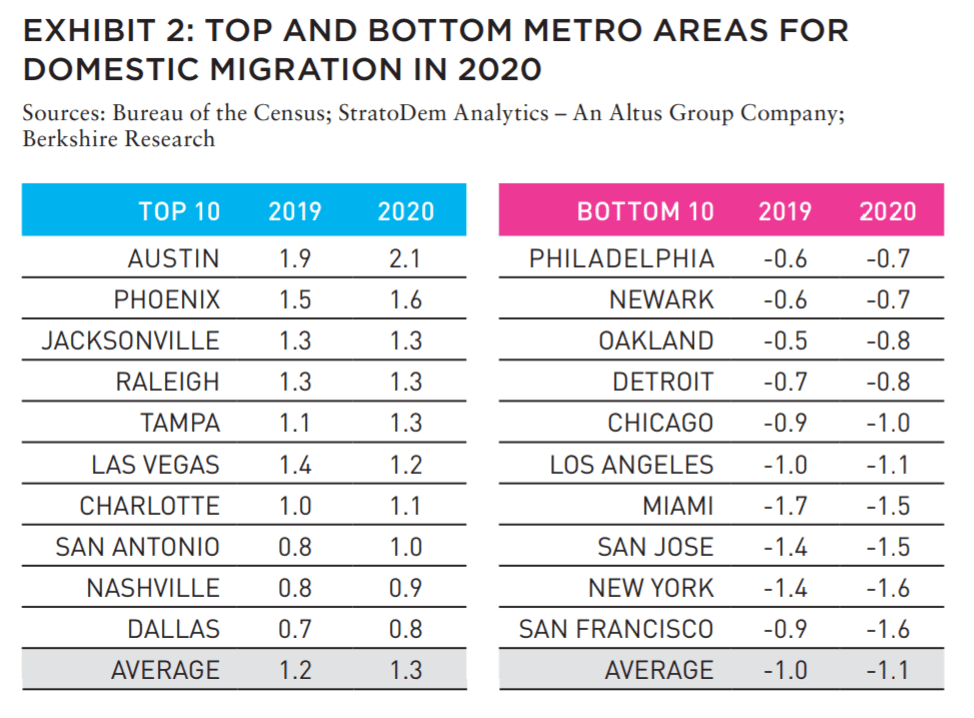

Our initial findings, which are now also supported by the recently released census estimates, have suggested that the pandemic did exacerbate domestic migration trends across markets that were in place for some time. As Exhibit 2 shows, domestic migration has indeed improved or kept pace in most metro areas or divisions where it was already strong before the pandemic, but it has worsened on the opposite side of the spectrum.

In the case of the domestic trends within markets, the picture was more nuanced. The data show, for example, that the pandemic did not materially affect domestic migration trends for many major cities. In fact, urban population flows have even improved relative to the prior year in places such as Austin, Denver, Houston, Phoenix, Raleigh, San Antonio, Seattle, and Tampa. At the same time, the pandemic has reinforced migration out of the large and densely populated major cities in gateway markets, including New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, and San Francisco.

Our preliminary analysis suggests that most of the people who left those cities last year moved into neighboring suburbs. Despite the influx of new dwellers, suburbs still have experienced net out-migration at about the same rates as before the pandemic. In other words, both cities and suburbs experienced net population move-outs into other markets—usually in other states. Texas, Florida, Tennessee, Arizona, and Nevada were among the major beneficiaries of these trends.

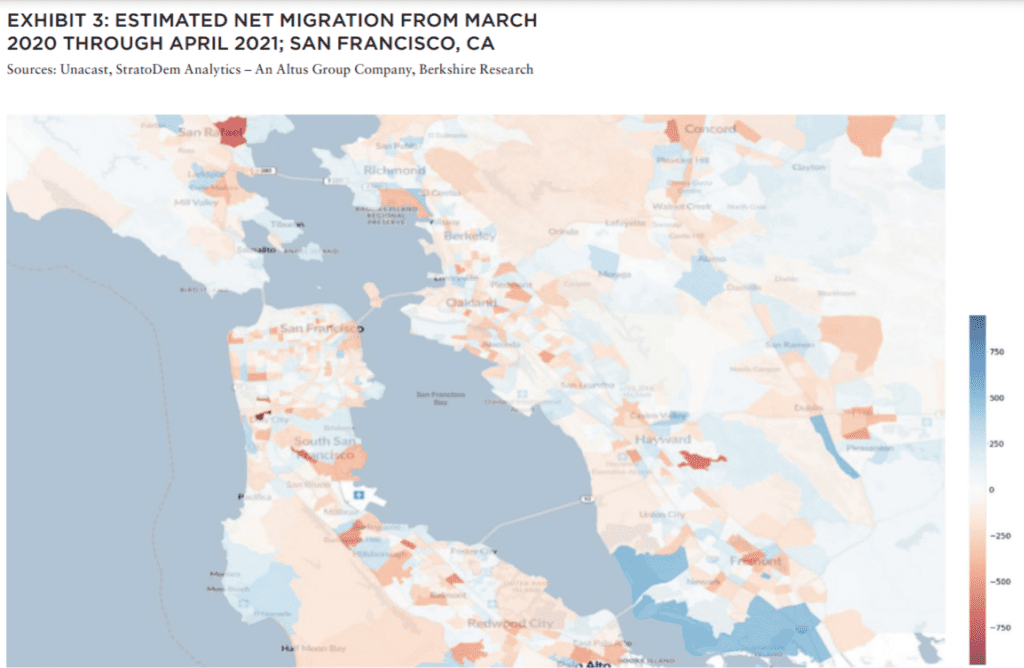

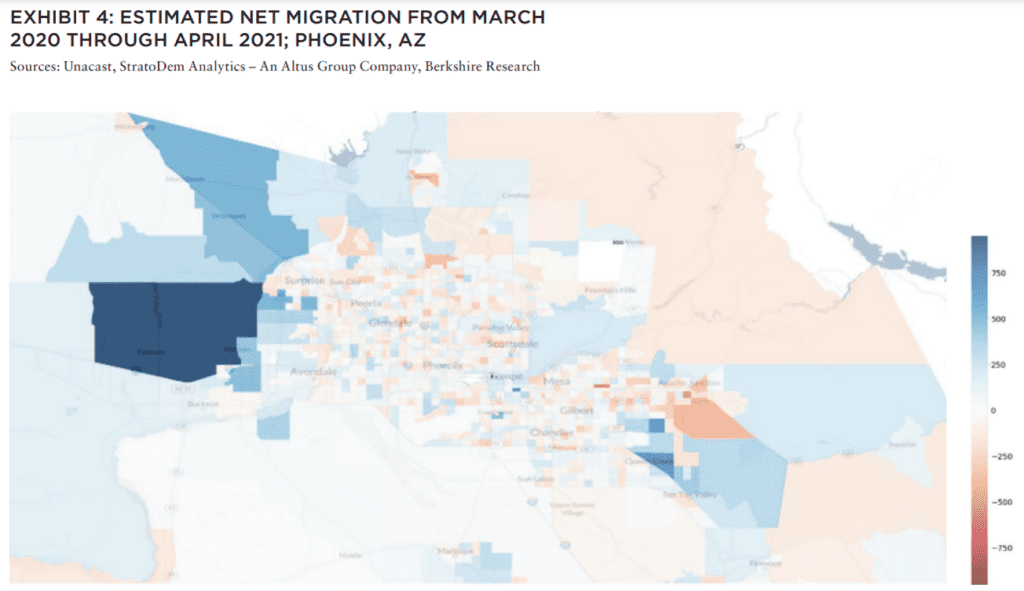

The new data allows us to look at the population flows even more closely and to have a fuller picture of how migration trends varied within cites or suburbs, as well as in terms of demographic profile of the movers. For example, Exhibit 3 shows that while the San Francisco metro area lost population last year, some neighborhoods in the area added hundreds of new residents. Meanwhile, some of highest migration flows into Phoenix took place in large, rapidly expanding master-planned communities west of the city, such as Tartesso and Verrado.

It was also instructive to find out that a typical migrant from San Francisco to Phoenix was 39 years old with a household income of approximately $150,000, while those moving from Phoenix to San Francisco were 37 years old with a much lower household income of $88,000.

LOOKING AHEAD

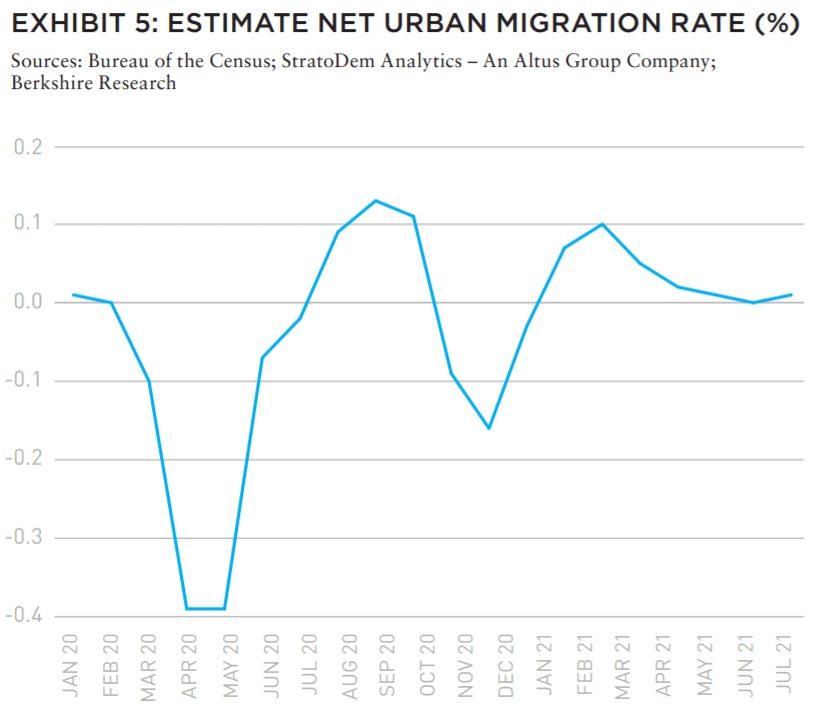

As the public health situation improves, most of the population losses or gains directly linked to the pandemic are likely to be temporary, depending on the location. To illustrate this, Exhibit 5 shows estimated implied rates of migration into and out of urban neighborhoods in gateway markets that experienced tangible negative migration flows last year, measured using monthly mobile phone data.

In these cities, population flows were closely tied to the two waves of new infections in the spring and winter. As the waves of infections subsided, migration flows quickly turned positive, suggesting that the pandemic-related move-outs would partially reverse as the economy re-opens, depending on how flexible businesses would be regarding work-from-home arrangements with their employees. At the same time, the data also show that urban migration has slowed, or in some cities, went negative again as the Delta variant caused more aberrations.

The pandemic is still only part of the story. These cities (and in most cases, their suburbs as well) were already experiencing negative domestic migration before 2020, and it will take time for those trends to stabilize or turn around. It is certainly encouraging for many investors to see that people have come back into urban areas, but the real recovery will only start when domestic migration exceeds pre-pandemic rates— which has yet to take place.

DOING MORE WITH REAL-TIME DATA

Mobile phone data is a powerful alternative source for evaluating domestic migration across and within markets. It allows us to track it with high frequency and granularity, including stratification by age and income, and can also be used to predict near-term population flows and potentially other demographic trends.

In the hypothetical example in Exhibit 2, for instance, a one-foot rise from As with any new data source, further research will be needed to better understand the full range of its potential applications, but it is already proving to be quite effective in explaining variations in regional growth patterns, as well as the factors that might be driving them.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Michael Clawar is Vice President of Data Science for StratoDem Analytics—An Altus Group Company. Gleb Nechayev is Senior Vice President, Head of Research for Berkshire Residential Investments. The authors also thank Danny Kaminsky of StratoDem Analytics for his data support.

—

NOTES

This material is for informational purposes only and is not intended to, and does not constitute financial advice, investment management services, an offer of financial products or to enter into any contract or investment agreement.

1 StratoDem Analytics integrates raw mobile phone data provided by Unacast with StratoDem economic and demographic nowcasting and forecasting to measure aggregate migration rates at the neighborhood level by household characteristics.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE (FALL 2021)

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR / GROUPTHINK VS. GROUP COLLABORATION

AFIRE | Benjamin van Loon

MID-YEAR SURVEY / CHECKING THE PULSE

No matter your age or experience, 2021 has shaped up to be a year that no one can forget. Findings from the AFIRE 2021 Mid-Year Pulse Survey detail a cautious road ahead.

AFIRE | Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon

CLIMATE CHANGE / REASSESSING CLIMATE RISK

The commercial real estate industry may not yet fully grasp the actual relationship between climate risk and asset pricing and value. But the knowledge is coming fast.

York University | Jim Clayton

University of Reading | Steven Devaney and Jorn Van de Wetering

Kinston University | Sarah Sayce

UNEP FI | Matthew Ulterino

NON-TRADITIONAL / THE ALLURE OF SPECIALTY SECTORS

Real estate investments have historically coalesced around common property types—but it may make sense for investors to reconsider specialty property sectors in the post-COVID world.

Invesco Real Estate | David Wertheim

NON-TRADITIONAL / NON-TRADITIONAL IS GOING MAINSTREAM

The mainstreaming of nontraditional property types is well on its way within institutional investing, which will materially broaden the real estate investment universe.

Principal Real Estate Investors | Indraneel Karlekar, PhD

DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE / DIVERSIFYING INTO DIGITAL

As investors look for sustainable sources of inflation-protected yield, real estate investment is increasingly blurring into a wider range of “digital” real asset investment strategies.

AECOM Capital | Warren Wachsberger, Josh Katzin, and Corbett Kruse

LIFE SCIENCES / TAPPING INTO BIOTECH

Over the past two decades, the single-family rental industry haLife sciences real estate has been a “hot” property type for the past decade—and even more since the pandemic. Will all the capital targeting the space be placed where it needs to go?

RCLCO | William Maher, Ben Maslan, and Cecilia Galliani

ESG + CLIMATE CHANGE / HIGH-WATER MARKS

Interest and excellence in ESG performance is becoming increasingly critical to portfolio strategy. So with sea levels on the rise, how can portfolios stay above water?

Barings Real Estate | Jerry Speltz

ESG + NET-ZERO / VALUING NET-ZERO

With more tenants focusing on environmental targets, the burden to reduce direct emissions places increased pressure on investors, who are at a pivotal moment in ESG strategy.

JLL | Lori Mabardi, Emily Chadwick, and Eric Enloe

ESG + FAMILY OFFICE / FAMILY OFFICES AND ESG

As sustainable investing continues to grow in popularity, family offices have taken note—and understanding ESG targets and regulations will be key for longterm performance.

Squire Patton Boggs | Kate Pennartz and Rebekah Singh

DEBT / WHY DEBT, WHY NOW?

Debt funds remain a comparatively small part of the real estate investment market, but they have been gaining in prominence in recent years.

USAA Real Estate | Karen Martinus, Mark Fitzgerald, CFA, and Will McIntosh, PhD

MIGRATION / MIGRATION IN REAL TIME

As the public health situation started to improve in early 2021 and the economy reopened, did migration flows change too—and what if we are able to answer this in real time?

Berkshire Residential Investments | Gleb Nechayev

StratoDem Analytics | Michael Clawar

URBANISM / DOWNTOWN DISRUPTION

The pandemic-driven changes to downtown areas and central business districts is changing the geography of institutional investment. What else changes because of this?

Drexel University | Bruce Katz

FBT Project Finance Advisors + Right2Win Cities | Frances Kern Mennone

WORK-FROM-HOME / CHOOSING FLEXIBILITY

Employees are increasingly demanding flexibility and choice for where (and when) they work. What strategies can landlords implement to adapt?

Union Investment Real Estate | Tal Peri

TALENT AND RECRUITMENT / TALENT PARITY

To be better prepared for future risks, firms need diverse talent. So is the goal of 50% female representation achievable in global real estate investment and asset management firms?

Sheffield Haworth | Isabel Ruiz

CLIMATE CHANGE / PREDICTING THE CLIMATE FUTURE

We are all invested in the cities, assets, and infrastructure of tomorrow, even if we might not live to see the ten largest cities in 2100. But understanding climate change can get us closer.

Climate Core Capital | Rajeev Ranade and Owen Woolcock