Without a framework that considers the causal factors underpinning the current office market dislocation, investors are left sifting through millions of square feet of office space in search of the right property.

The tide of investor sentiment has turned definitively against the office sector. Publicly traded office REIT share prices have fallen by 44% from March 2022 through December 2023, portending further declines for private valuations, which were down an estimated 30% over the same period.

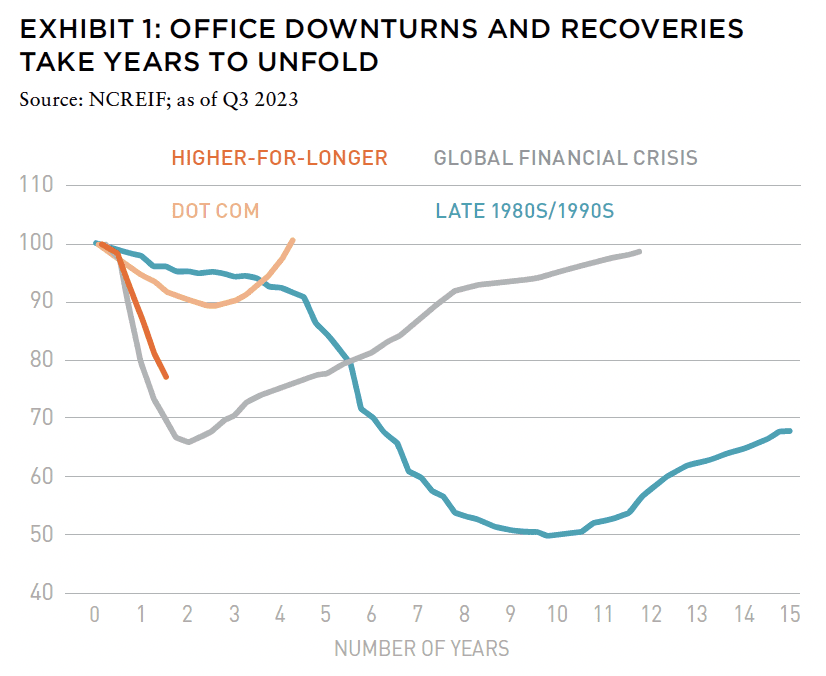

While office utilization has slowly crept back up following the pandemic, it is still short of where it was prior to COVID. Office downturns can take years to play out, as the industry experienced during the late 1980s to early 1990s Savings and Loan Crisis (S&L). The GFC and dot-com downswings lasted slightly more than two years, and the current higher-for-longer dislocation has lasted almost two years.

However, in no prior downturn has office faced such an existential threat due to remote work. Additionally, there are few indications of a “bottom” to office values presently, and even once values stabilize, the prospective recovery would still be tenuous.

New office leasing generally necessitates significant capital outlay on the part of the owner. This is in the form of tenant improvements by which space is reconfigured to accommodate the tenant’s space needs and preferences. Tenant improvements are an upfront cost to the owner that is usually amortized over the lease term. However, in the post-pandemic era, tenants are more inclined to downsize their space footprint while landlords, faced with weakening demand, are understandably hesitant to accommodate tenant improvements—especially given the spike in construction costs.

Debt costs were accretive to office values when the Fed Funds rate was near zero. However, with the policy rate above 5% and lenders averse to increasing their office exposure, financing has become prohibitively expensive for borrowers. Rents are being slashed and lease terms truncated as landlords struggle to retain, much less attract, tenants. Anecdotally, some institutional-quality office properties are pricing below their loan balances. At present, distress appears imminent.1

Investors willing to brave this dislocation are likely to find ample opportunity in this sector. There are approximately $400 billion of office loans scheduled to mature from H2 2023 through 2027, and while not all those loans are challenged, many are, or will be. Given the rising risk of functional obsolescence, the potential for missteps is high, and the rest of this article will deal with a framework for parsing upswell in distress around the office property type.

INSTABILITY AMONG REGIONAL BANKS

The last period of pervasive distress for US commercial real estate was over a decade ago during the aftermath of the GFC. While distressed real estate investors found it challenging to capitalize on opportunities created by the pandemic, they now see an opportunity following the rapid monetary tightening orchestrated by the US Federal Reserve. There are commonalities between market downturns: overleverage and a prolonged lack of liquidity are often cited as causal factors, but it is usually an event or series of events—shocks if you will—that serve as a catalyst.

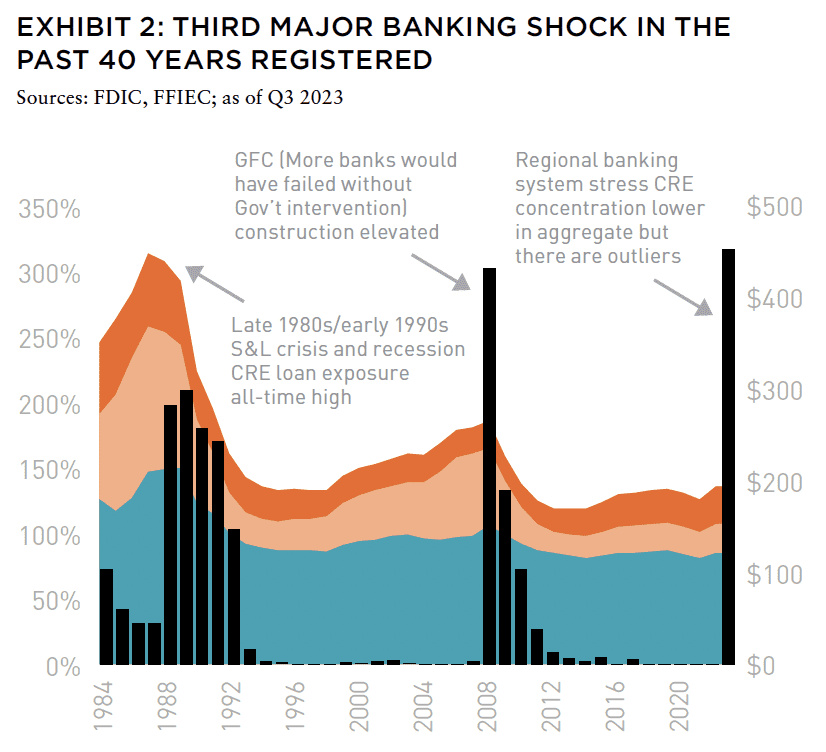

A key catalyst recently was the sudden failure of three large regional banks—First Republic, Silicon Valley, and Signature—between March and May of 2023. The pivotal moment came when these banks’ securities portfolios generated significant unrealized losses, which caused deposit outflows, forcing some lenders to realize the losses by selling bonds to create liquidity, resulting in further deposit runs and regional banking system stress.

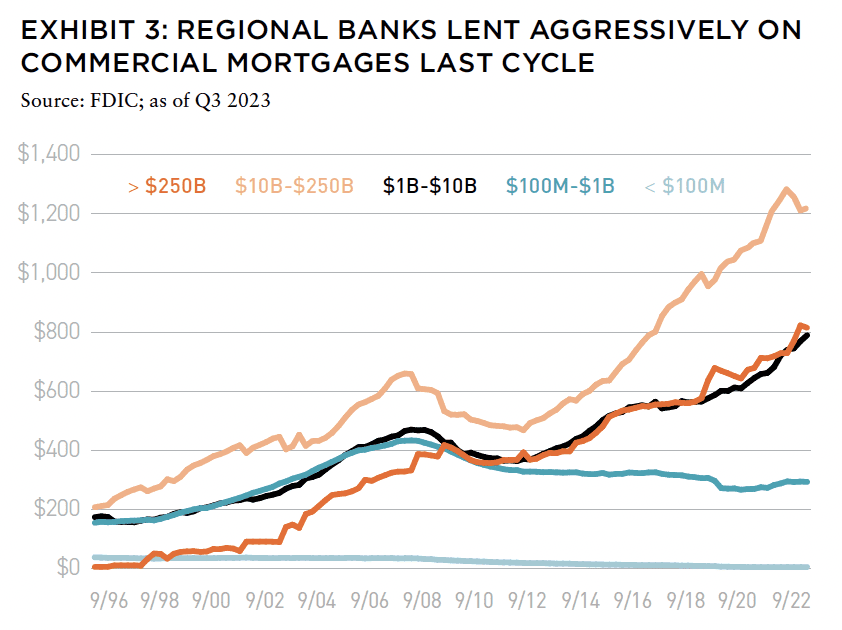

For more than a decade, regional banks with $10–$250 billion in total assets have been an active commercial mortgage lender. Their exposure increased from $468 billion outstanding as of 2012 to $1,207 billion outstanding in the second quarter of 2023. Although each cycle is different and the banking system is better capitalized today, the environment has parallels with two other banking system shocks: the S&L crisis and the GFC. Facing deteriorating liquidity positions and overexposure to CRE, regional banks are now in retreat from the commercial mortgage market, exacerbating the shortage of debt capital that office investors had come to rely so heavily upon.

The regional banking system is diverse with lenders focused on different segments of the CRE market. Super-regional banks ($250–$650 billion total assets) tend to have a national portfolio and are more likely to have institutional quality STEM office properties.2 Meanwhile,, smaller regional banks ($10–$250 billion total assets) focus more so on their local markets and their portfolios are generally less weighted towards higher-end buildings.

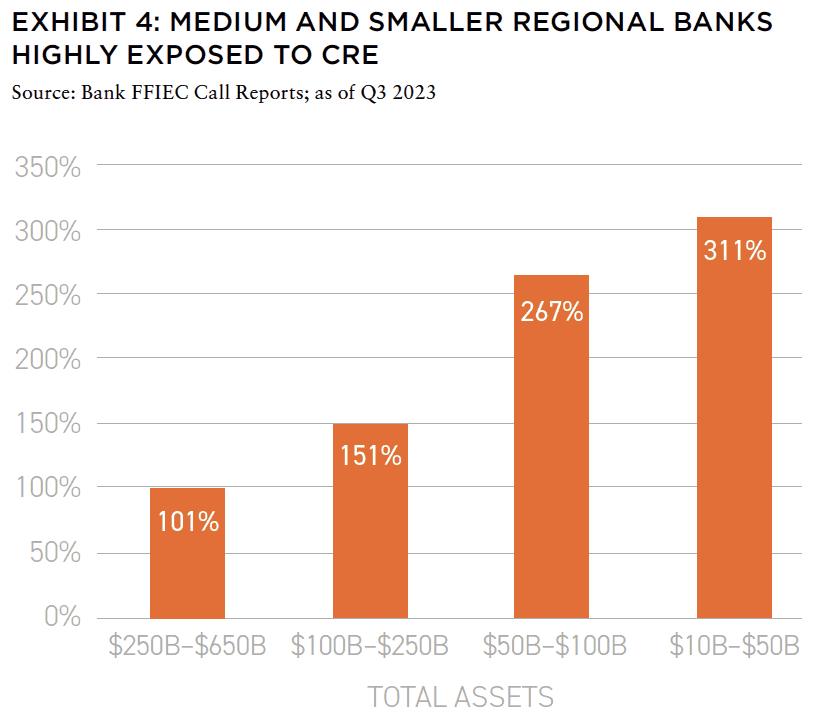

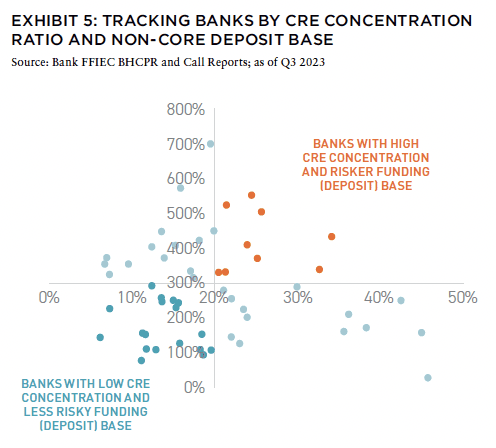

In addition, super-regional banks tend to carry a broader range of loans on their balance sheets, whereas smaller regional lenders are more exposed to CRE loans, particularly as the bank size declines. As an example, super-regional banks’ CRE concentration ratio—the amount of CRE loans outstanding relative to the amount of risk-based capital—was 101% as of Q3 2023 compared to 311% for regional banks with $10–$50 billion total assets based on an analysis of approximately sixty banks.

This poses a risk for certain regional banks as the FDIC recently noted loans backed by office properties “face challenges,” while Fed and OCC research shows banks with elevated CRE exposure had significantly higher failure rates during past downturns and are a focus of supervisory exams. The regional banking system’s CRE challenges can be compounded by a weaker funded base, such as uninsured deposits, which are also vulnerable from unrealized losses on their securities portfolio.

Although the overall banking system has been resilient, there are challenged banks and negative outliers. Their issues present opportunities as problem office loans continue to materialize. As an example, nonfarm nonresidential real estate loans, which includes office property loans, 30+ days past due delinquency rates increased 55 BPS year-over-year to 1.26% as of Q3 2023, while some banks increased their allowance for loan losses given weaker expected office mortgage performance.

These headwinds may create incentives for banks to sell loans, potentially at a discount, to repair their balance sheets and raise liquidity. This would likely create distressed opportunities for well-capitalized investors.

A DIFFERENT APPROACH FOR A DIFFERENT DOWNTURN

Plenty of headlines lament the confusion created by the current market’s deviation from its historical pattern. Intense monetary tightening has not “broken” the economy as it has in prior cycles. Rather, fundamentals have been resilient as valuations faltered. Consumer spending and the labor market have defied repeated prognostications of their imminent collapse.

Even experienced distress investors concede that distress investing can be loosely defined. Outside of buying discounted bank notes or foreclosure properties, there are many ways to provide short-term equity or debt capital that allows a borrower time to avoid an impending default or foreclosure. Distressed capital often plays in gray areas, and there are myriad variations to “kicking the can”. Preqin reports that in the US alone there is $269 billion of dry powder—capital committed in real estate real estate funds but not yet deployed. At points in the market cycle, capital often finds a way of providing an interim solution for troubled borrowers.

For those that approach opportunities by assessing capital stack restructuring, theirs is ultimately akin to finding the proverbial needle in the haystack. Though accomplished distress investors have deep industry connections that can reduce search costs, it can also be an excruciating waiting game. Often, the investors who wait for distress to land on their desk can end up feeling like there are far fewer opportunities than they expected. Past cycles can provide a helpful reference, but without discerning the fundamental causal factors leading to dislocation, history and experience are only partial guides.

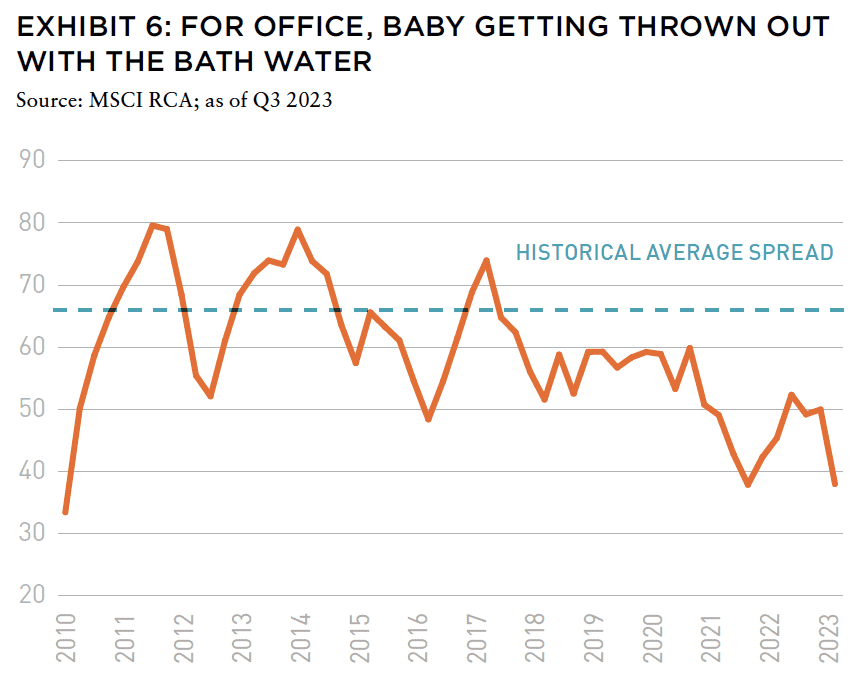

A refreshed approach to distress investing is necessary today. Functional obsolescence is foremost on the minds of investors. Even nominally Class A office properties that seemed viable prior to the pandemic are now outmoded as workers and firms embrace hybrid work arrangements. The causal link between office-using employment and office space absorption has diminished greatly. Nationally, office-using payrolls are 6% above their pre-pandemic peak even as office vacancy has risen to record highs. Obsolescence risk is evoking fear among investors to the extent that many are now avoiding new investment in the property sector entirely.

However, there are office properties that remain well-leased and command premium rents. These high-quality properties are found in desirable live-work-play neighborhoods that can help firms attract and retain talent while promoting firm culture and collaboration. Understanding the difference between a defunct asset and one that either is or could become a next-generation STEM office building is critical to a successful investment outcome. For the past few years, investors have been less discerning in the differentiation between the “haves” and “have nots” as illustrated by the diminishing spread between top tier properties and commodity space.

For those investors able to employ an operational lens against the thousands of buildings that constitute troubled or distressed loan portfolios, there are meaningful discounts for relevant office properties. However, without a framework that takes into consideration the causal factors underpinning the current market dislocation, investors are left sifting through millions of square feet of office space in search of the right property—a daunting task even considering how much informational transparency has improved for the CRE industry. Identifying at-risk lenders—especially certain regional banks—and their recent office loan originations makes the search much more manageable and ultimately accessible.

IN THIS ISSUE

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR: WELCOME TO #14

Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

INSURING FOR ELSEWHERE: CLIMATE-RESPONSIVE REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT

Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

INSURING FOR ELSEWHERE: STRIPPING THE CASHFLOW FROM THE DEAL

Paul Fiorilla | Yardi

MARKET OUTLOOK: MODEST GROWTH AND RETREATING INFLATION IN 2024

Martha Peyton, CRE, PhD | LGIM America

UNDERPERFORMANCE PARADOX: NEW RESEARCH QUESTIONS THE VALUE OF PRIVATE REAL ESTATE FUNDS

William Maher, Taylor Mammen, Ben Maslan | RCLCO Fund Advisors

NAVIGATING THE CURVE: RESILIENCE, ADAPTATION, AND PREPARING FOR 2024

Jack Robinson, PhD | Bridge Investment Group

LIQUIDITY FREEZE: POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS FOR COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE

Christopher Muoio | Madison International Realty

SUPPLY WAVE: REASON FOR OPTIMISM IN THE MULTIFAMILY SECTOR

Sabrina Unger, Britteni Lupe | American Realty Advisors

MANAGE WHAT YOU MEASURE: UNDERSTANDING EXPENSE INFLATION IN APARTMENTS

Gleb Nechayev | Berkshire Residential + Webster Hughes, PhD | ThirtyCapital

PARSING OFFICE DISTRESS: PLANNING FOR THE NEXT GENERATION OF OFFICE SPACE

Dags Chen, Lincoln Janes, CFA | Barings Real Estat

MODEL STATES: USING ECONOMIC STATE MODELS TO ASSESS THE US OFFICE OUTLOOK

Armel Traore Dit Nignan | Principal Real Estate

OUTWARD SHIFT: WILL THE LOGISTICS SECTOR CONTINUE TO OUTPERFORM?

Kerrie Shaw | AXA IM Alts

HARNESSING THE WIND: TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE AND THE PROMISE AND PERIL OF AI FOR REAL ESTATE

Nikodem Szumilo | University College London + Chris Urwin | Real Global Advantage

MIND YOUR DATA: REAL ESTATE INVESTING, FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF A DATA NERD

Ron Bekkerman, PhD

OPERATING EXPENSES RISING THE OTHER MAJOR COMPONENT OF NOI GETS MORE FOCUS

Stewart Rubin, Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

IN MEMORIAM: JANICE STANTON

+ LATEST ISSUE

+ ALL ARTICLES

+ PAST ISSUES

+ LEADERSHIP

+ POLICIES

+ GUIDELINES

+ MEDIA KIT (PDF)

+ CONTACT

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dags Chen and Lincoln Janes are on the US Real Estate Research and Strategy team for Barings Real Estate, a global real estate platform with extensive capabilities across both debt and equity strategies.

—

NOTES

1. See also: Dags Chen. “Workplace Values.” Summit Journal. https://www.afire.org/summit/workplacevalues/. Accessed January 30, 2024.

2. STEM office refers to office in geographies where 40% of the population has at least a bachelor’s degree and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics sector employment is at least 5% of total employment.

—