This article appears in Summit Journal (Summer 2020) | Download PDF

A DISPATCH FROM THE 2020 AFIRE WINTER CONFERENCE

When AFIRE members gathered at the Mandarin Oriental for the annual AFIRE Winter Conference earlier this year, few suspected that it would likely be one of the last in-person real estate conferences in 2020.

Attendees recognized that COVID-19 was a concern, especially for those doing business in China at the time, but the threat still seemed removed and abstract for many. It would be a few more weeks before everyone realized that the pandemic had already taken hold in Europe and the US. The resulting local and national disease prevention efforts enacted around the world would soon spark the economic and psychic gunpowder that will one day be marked as a singularly significant, explosive, and unprecedented event in modern history.

And yet, much of the discussion in February seemed to predict what is the center of mainstream political, social, and fiscal discussions taking place right now.

As the malignancies of COVID-19 spread in the following months (and continue to do so, even now), AFIRE members and other leaders across industries began to observe that the pandemic hasn’t brought anything new into the world, but it did accelerate what was already underway.

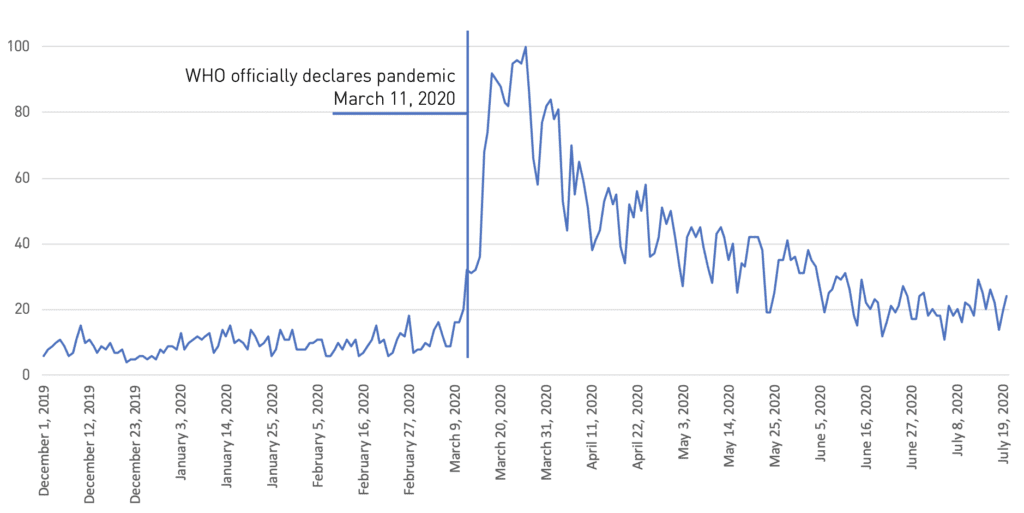

WORLDWIDE GOOGLE SEARCHES FOR “UNPRECEDENTED”

December 2019 – July 2020

Source: Google Trends

Note: Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term.

For example, pressure for sustainability isn’t new, but COVID-19 has heightened the urgency for resiliency and responsibility—for both investors and assets. The need for infrastructure investments and affordable housing isn’t new, but with many millions newly unemployed and cash-strapped, the need is now immediate and existential. Home offices and Zoom meetings aren’t new, but now they’re ubiquitous.

With these ideas already fomenting in the minds of AFIRE’s real estate leaders, the Winter Conference program was a prescient primer on understanding where we are today, and what we need to do (or stop doing) to be prepare our investors, employees, constituents, communities—and buildings—for tomorrow.

Can investments be used to stabilize democracy in urban centers?

Just as the pandemic has accelerated technological, infrastructural, and social changes already underway, it has also de-siloed physiology from more comprehensive concepts of well-being. Race, employment, geography, and socio-economic status have emerged as major factors to COVID-19 susceptibility, just as much as blood type and other physical health conditions, underscoring the interconnected relationship between economic performance and public health.

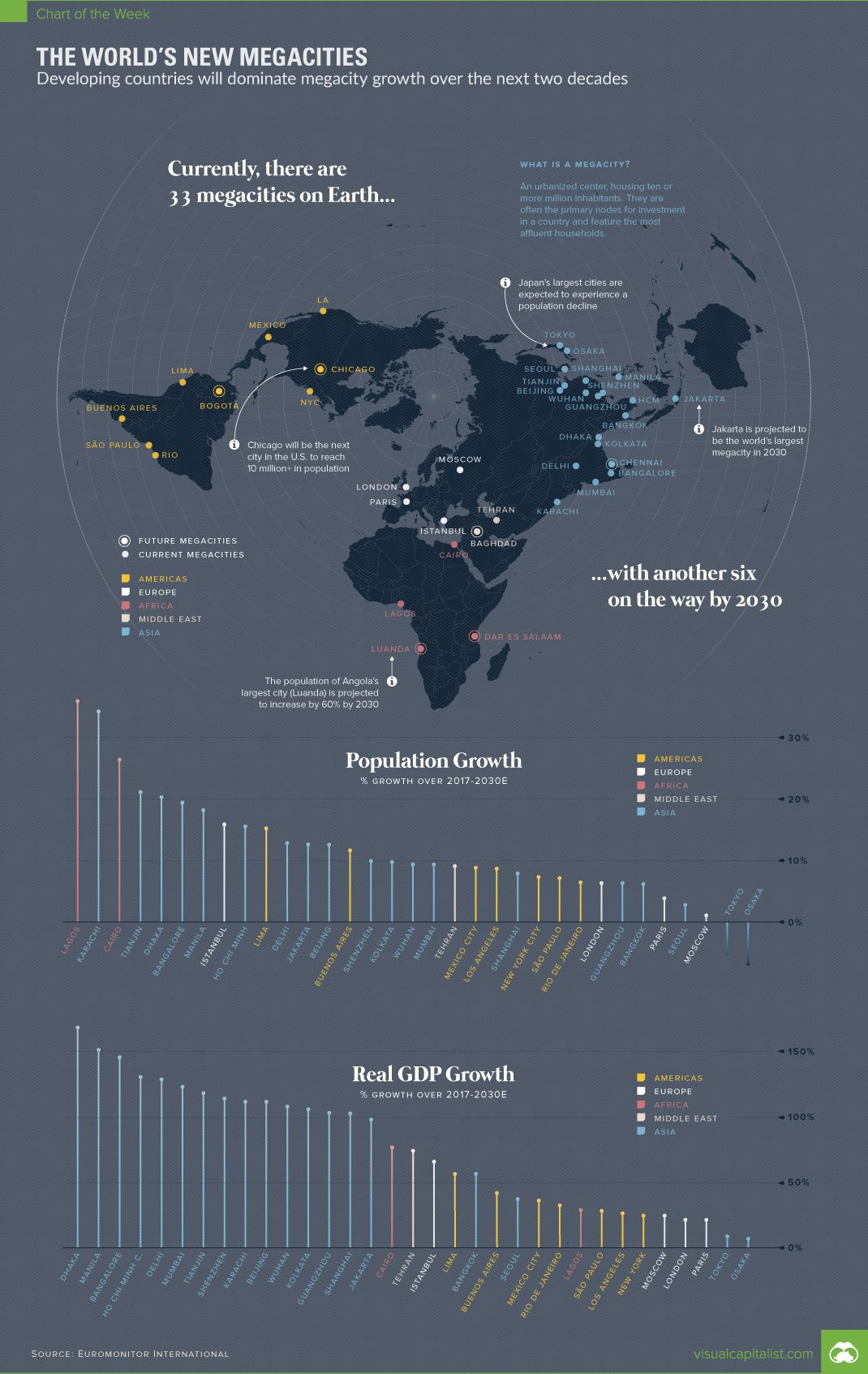

You can’t have vigorous, dynamic, and profitable cities without healthy people, and as we have seen, health is as much about disease and life expectancy as it is about education, literacy, opportunity, access, and mobility. Typically, these have been the same factors that have determined and driven urban growth since the beginning of the Industrial Age, including what Anthony Shorris sees as the rise of the world’s great megacities—New York, Los Angeles, Singapore, London, and other “somewheres.”

As a long-time public servant, former deputy mayor of New York City, current senior advisor at McKinsey and John Weinberg/Goldman Sachs visiting professor at Princeton University, Shorris recognizes the strengths of the megacity, and the critical role institutional and international capital holds these urban centers. However, Shorris cautioned, these megacities have become increasingly powered by the same winner-takes-all strategies that have exposed the limitations (and negative economic/health implications) of capitalism. These limitations are simultaneously playing out in other sectors, such as technology, where three or four players dominate the overwhelming majority of the market, leading to tensions in labor, politics, and diplomacy.

“First-mover advantages, regulatory capture, political influence, and agglomeration economics have fueled a winner-takes-all urbanism,” Shorris said. “This position can be good for short- and medium-term earnings, but affects the long-term view, and fuels tensions already rising in these economies.”

The economic dominance of megacities—just like the dominance of small groups of firms in various sectors, or the dominance of wealthy families and individuals relative to their populations—is enormous and growing. There are political ramifications to this. “Low-demand communities blame high-demand areas for their problems, and high-demand areas dismiss low-demand communities for being uneducated or irrelevant,” Shorris said, and in both cases, “where the winners take all, the majority is left behind.”

Political stability is the most critical ingredient for cross-border investing. For this reason, long-term investors can bring an important perspective into this paradigm, including developing better understanding of risks in their own portfolios, and may even have the ability to advance actions that support the infrastructure of stability that makes such investments possible.

In addition to increasingly accounting for climate risk and political stability in their own portfolio strategies, “investors need to think about how tense is the winner-take-all thinking of the economies in which they’re investing,” Shorris said. If the political actors in an economy are not managing such imbalances, they could be undermining asset performance. In these cases, “Investors should consider investing elsewhere—not only to maximize returns, but to think in terms of shoring stability. Cleveland and Milwaukee might actually be as important to America’s future as New York and San Francisco.”

For investors already exposed and performing well in megacities, Shorris warns against a cold exit, but instead encourages more expansive long-term strategies in other cities, ensuring that climate risks and politics are part of the equation. And as we have seen, COVID-19 is a likely signal of the challenges to come from large-scale political/social/existential disruptions caused by large-scale change in environments and economies.

What can COVID-19 teach about climate change strategies?

The damage and danger of COVID-19 could soon be instructive for navigating the impending hazards of climate change, which pose one of the most significant threats to long-term strategies for real asset investments. According to the World Health Organization, “changes in infectious disease transmission patterns are a likely major consequence of climate change.”¹

While it may be several years if and before a causal relationship is proven between climate change and COVID-19, official measures instituted over the past several months, such as mask wearing, social distancing, closure of indoor spaces, and remote working, establish yet another direct link between climate change, human behavior, and our usage of the built environment.

Disease has become a necessary part of understanding climate risk alongside sea-level rise, heat waves, wildfires, and other increasingly persistent weather events—all of which, according to Mary Ludgin, Senior Managing Director and Head of Global Research for Heitman, are “game-changers” for mapping long-term patterns used to identify locations of enduring value for investors—accounting for resiliency, water access, migration patterns, and other factors.

“Climate change is upending the notions we hold about where people and firms will congregate,” Ludgin said. “We need to be increasingly mindful that when we accept risk for our investments, we are taking on the risk of the municipality’s initiatives to keep its infrastructure working, and how it invests in mitigation and adaptation strategies to offset the effects of climate change.”

Understanding both state- and metro-level policies for infrastructure and climate issues is essential for informed investment decisions. With COVID-19 transferring infectious disease from the realm of abstraction into our lived experience, we now have a more immediate and knowable awareness that should work to elevate the necessity of this understanding—even for factors as rudimentary as migration. For example, between 2008 and 2018, 265 million were displaced as a result of natural disasters.² It remains too early to tell what the impact of COVID-19 will be on migration, but as addressed elsewhere in this publication, employment, outdoor accessibility, and safe buildings will be driving factors for ongoing migration trends, and these factors are a direct result of attitudes and policies about sustainability and climate change.

Metro-level strategies implemented to mitigate climate change effects, such as earth berms to guard against flooding, or net-zero construction mandates, could lead to new investment strategies, Ludgin said. And even as legacy coastal cities will see their climate defense battened, other better-protected cities, on higher ground and with better access to natural resources—especially fresh water—will potentially grow in importance and value for long-term investments.

Reimagining the built environment

With more drastic climate change effects on the near horizon, and COVID-19 still in the room, it will also critical for investors to track policies and regulations alongside changing social attitudes. As the pandemic continues, healthy buildings aren’t just engineering novelties and shiny facades for trade magazines—they’re the new baseline for ensuring safe experiences in the built environment, critical to the performance of assets in all sectors.

In his closing keynote address for the Winter Conference, Landscape Designer, Conservationist, Author, and Television Host P. Allen Smith used the idea of housing development to advocate for an overall paradigm shift in how communities are both served and organized.

“Our environments have been built largely by utility—strip malls, excessive freeways and highways, soulless architecture, poor management of power and congested roads,” Smith said, elucidating the difference between real estate that takes a myopic view of maximizing value per square foot, with little regard for context, and more thoughtful and integrated approaches to urban design and development. A paradigm shift, in other words.

As an example, Smith discussed his organization’s Pinewood Forest project in Fayetteville, Georgia, “a development that promises an eventual 700 new homes, 600 apartments, 300 hotel rooms, and some 270,000 square feet of commercial space with restaurants and retail,” according to Curbed Atlanta.³ Designed as a mixed-use community integrating traditionally suburban single-family house and yard concepts with the principles of urban density, walkability, and ample community spaces, the project aims to strike a balance between both environments to create a new real estate idyll.

Of course, Smith said, “A new paradigm isn’t really new it all. It’s looking around and asking what actually means something important to us.”

As much of the world hit a pause button in early 2020, and as we continue our uncomfortable transition into a post-COVID-19 era, people and organizations at all levels have been asking exactly questions similar to those posed by Smith: Do I really need to get on an airplane every week? Why do I live in this city if I no longer need to commute to the office? Where can I get access to more green space? Does a five-day work week actually make sense?

These questions derive from the same social consciousness that has driven other paradigm shifts and ideological evolutions throughout history. As Thomas Kuhn wrote in his influential work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (where the term “paradigm shift” was coined):

The transition from a paradigm in crisis to a new one from which a new tradition of normal science can emerge is far from a cumulative process, one achieved by an articulation or extension of the old paradigm. Rather it is a reconstruction of the field from new fundamentals, a reconstruction that changes some of the field’s most elementary theoretical generalizations as well as many of its paradigm methods and applications.⁴

Facing emerging crises and uncertainties in economies, foreign relations, and social attitudes—with the threats of climate change looming on the near horizon—the real estate investment industry is facing a paradigm shift of its own. And as Kuhn writes further on, “As in political revolutions, so in paradigm choice—there is no standard higher than the assent of the relevant community.”

Just as real estate has embraced and led the charge for better sustainable practices over the past several decades, so too should it lead the assent for a new paradigm choice that looks beyond the next quarter and into a long and healthier future.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Benjamin van Loon leads communications and publications for AFIRE, the association for international real estate investors focused on commercial property in the United States. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of Summit.

—

NOTES

1. World Health Organization, “Climate Change and Human Health,” World Health Organization (July 15, 2020), who.int/globalchange/climate/summary/en/index5.html

2. Sylvain Ponserre and Justin Ginnetti, “Disaster Displacement: A Global Review, 2008–2018,” Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, May 2019, internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/201905-disaster-displacement-global-review-2008-2018.pdf

3. Sean Richard Keenan, “How a New Town Tied to Georgia’s TV and Film Industry is Rising South of Atlanta,” Curbed Atlanta (August 14, 2019), atlanta.curbed.com/atlanta-photo-essays/2019/8/14/20804376/pinewood-forest-studios-atlanta-fayetteville-mixed-use

4. Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964)

—