In recent years, workforce and affordable rental housing in the US has emerged as a meaningful, demographic-driven opportunity for real estate investors, both domestic and international. Workforce and affordable housing is a crucially-needed product for the US housing market, and we have seen demographic and economic conditions amplify this need in recent years.

For instance, as of the most recent US Census Bureau data, there has been tremendous demand for rental housing with more than one million new renter households formed.

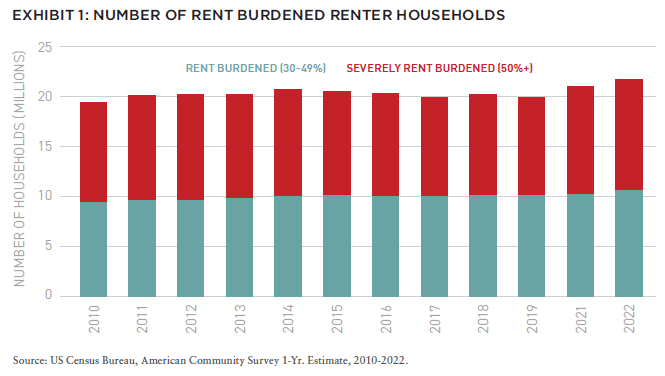

Shockingly, four out of five of those new households were rent-burdened, meaning that they paid more than 30% of income on rent. This illustrates the significant housing affordability challenge we have in the US—one that we believe can be addressed through private sector strategies.1

The lack of affordable and workforce housing is not a new problem in this country—but it is persistent and becoming more acute. While there are many nuances to how we got here, stated most simply, this is fundamentally a result of decades of an undersupply of attainable housing amid growing demand by moderate income households.

These entrenched housing fundamentals were further exacerbated as pandemic-driven shocks throughout the housing market resulted in rapid rent growth, pushing the share of cost-burdened households higher over the course of the past three years.

The US model of workforce and affordable rental housing is unique relative to international affordable housing models, which are often deeply subsidized by public funds and targeted towards the lowest-income households, in that the US system serves a broad range of income levels.

In addition to the deeply affordable segments most often associated with affordable housing, this sector addresses the housing needs of middle-income earners, including teachers, healthcare workers, and service professionals, who are essential to the fabric of thriving communities but are increasingly priced out of market-rate rental housing and the homeownership market.

It is clear why the segment of housing targeting moderate incomes has been largely absent from development pipelines: rising construction costs, particularly for land and labor, have made it financially unfeasible to build anything other than high-end Class A luxury housing. Historically, developers’ abilities to increase affordable housing units in the US has been limited to federally subsidized options like low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC);2 similarly, Section 83 vouchers have helped to provide households with access to existing multifamily units. However, both programs primarily target households earning less than 60% of the area median income (AMI),4 often prioritizing those earning below 30% to 50% of AMI. While these programs are vital for low-income families, they fall short of addressing the needs of the “missing middle,” leading to a significant increase in the number of renters who are cost-burdened or severely cost-burdened (Exhibit 1).5

In our view, private sector solutions that preserve, rehabilitate, and develop high-quality workforce and affordable housing are not only much needed but also are highly attractive for private investment. We believe that there is an opportunity to preserve and rehabilitate existing multifamily housing that is affordable to households earning less than 80% of area median income—the largest segment of US renters in the country. In our view, differentiated strategies seek to not only address residents’ physical needs for high-quality affordable housing, but also provide life-enhancing, on-site programs that advance social and economic mobility for residents and communities.

ASSET PROFILE: IDENTIFYING NATURALLY OCCURRING AFFORDABLE HOUSING

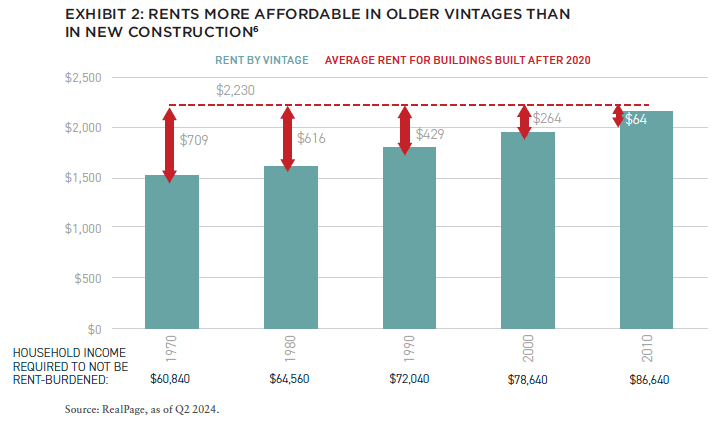

Traditionally, naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) has been identified through a rudimentary method of comparing individual property rents with market rents and applying a discount to determine relative affordability. This approach, while straightforward, typically leads to the identification of older asset vintages that offer meaningful discounts relative to market rents. However, older properties frequently come with trade-offs, including dated amenities that do not meet current resident expectations and deferred maintenance issues that, if unaddressed, can pose significant risks to both asset longevity and resident safety.

From a sheer volume perspective, there are thousands of assets for sale each year that are sub-optimally or inefficiently managed, and these assets can thrive with a hands-on operational touch. A well-crafted preservation and rehabilitation strategy increases the longevity, safety, and attractiveness of old or out-of-date exteriors and unit interiors while maintaining affordable rents.

In recent years, the limitations of a discount-to-market-rent-only approach to identifying NOAH workforce and affordable properties has become increasingly apparent. Beginning in 2020, pandemic-related disruptions have led to a sharp increase in rents, significantly raising the proportion of cost-burdened households over the past several years, especially as Class B housing supply has remained constrained. This has caused affordability pressures to extend into markets—and assets–that were once considered relatively affordable.

With significant rent increases across many markets, it has become clear that many renters’ incomes have not kept pace with rent growth. As a result, the traditional rent comparison method may fail to accurately reflect the true affordability of a property. Properties that appear affordable based on a simple discount-to-market rent may still be financially out of reach for many households when considering income levels.

Given these dynamics, a rent-to-income approach is now seen as a more appropriate method for determining affordability within the workforce and affordable sector. By assessing rents in relation to tenants’ incomes, this approach provides a more accurate measure of what is truly attainable for households. Furthermore, we can enhance our ability to identify NOAH properties by comparing rent levels to AMI, helping to pinpoint for which income segments of the population these properties are best suited. This methodology ensures that NOAH workforce properties are aligned with the needs of households that are most at risk of becoming cost-burdened, thereby mitigating financial strain and promoting housing stability.

THE “MISSING MIDDLE” RENTER COHORT

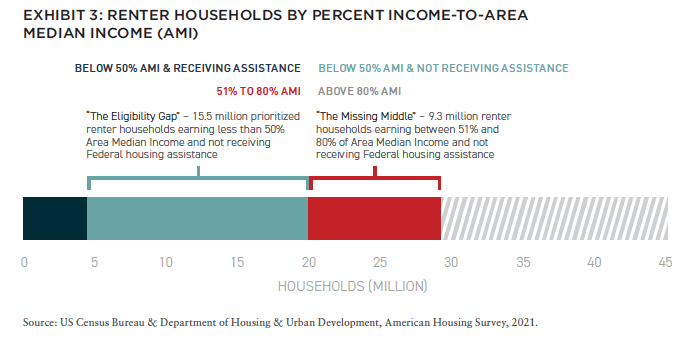

Workforce and affordable housing is critical to serving the needs of “missing middle” renters who qualify for federal housing assistance but do not receive it.

Nationwide, less than one in six renters earning less than 80% of AMI actually receive support, whether in the form of federally subsidized housing, vouchers, or other local government assistance. This shortfall has left a staggering 24.8 million in-need households on the outside looking in.7

This chronically underserved middle market is overwhelmingly made up of people who are actively engaged in the workforce,8 many in essential occupations such as teachers, police, firefighters, healthcare professionals, and municipal workers.

From both an education and age demographics perspective, renters in the missing middle do not differ markedly from higher-income renters, and approximately one out of every three of these households includes children under the age of 18.9 Without a full range of affordable housing options, many metros in the US risk losing residents and families that are vital to the social, cultural, and economic fabric of a city.

HOLLOWING OUT THE BOTTOM: THE EROSION OF EXISTING SUBSIDIZED HOUSING

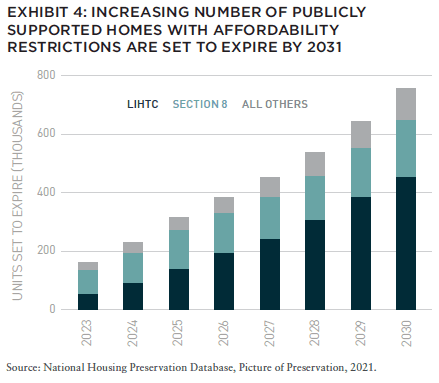

A key reason that missing middle renters face constrained housing options is that the market is operating against a backdrop of eroding supply of affordable homes, further underscoring the need for private sector measures to preserve low-cost housing.

An estimated 640,000 affordable rental units could revert to market-rate status by 2030 as federal rent caps reach the end of mandates, to say nothing of potential losses related to the expiration of state and local restrictions.10

Overall, we believe that the decreasing protections for subsidized housing will only compound affordability challenges for workforce and attainable housing as there will likely be not only a loss of affordable housing, but these properties are likely to revert to market rate housing and increase average market rent levels as well.

CHALLENGES IN ADDING NEW STOCK, ESPECIALLY AFFORDABLE OPTIONS

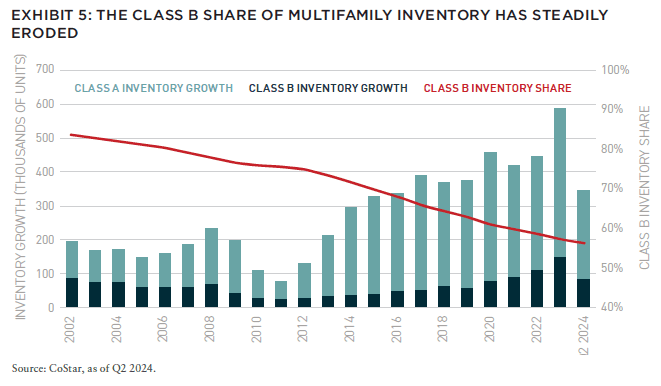

Missing middle renters must also contend with the fact that new multifamily development in recent years has overwhelmingly targeted luxury product offered at unattainable price points, while the stock of workforce and affordable housing has been stagnant. Despite recent increases in the number of Class B units delivered each year, the Class B share of total multifamily inventory has continuously dropped over the past two decades,11 which combined with a broader lack of affordability has resulted in pent-up demand and a substantial supply gap.

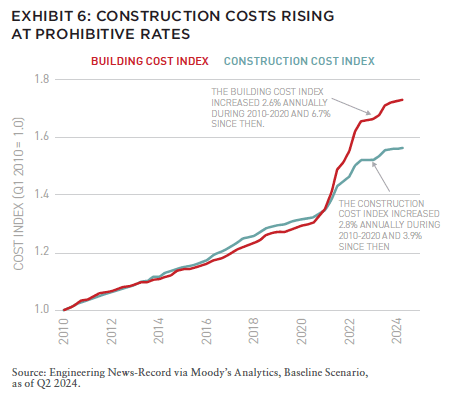

Since 2000, rising construction costs, particularly for land and labor, have made it financially unfeasible to build anything other than high-end Class A luxury housing. According to a widely respected cost index, overall construction costs have increased by 3.9% annually and building costs by 6.7% annually since 2020, exacerbating these financial challenges.12 These escalating costs have placed significant pressure on developers, and as a result, many have shifted their focus toward luxury developments, where higher rent premiums are necessary to achieve acceptable returns on investment. While LIHTC has proven effective on the margins in incentivizing new development of affordable housing with 100,000 units rehabbed or built in a typical year, the program is unlikely to shake loose enough affordable homes without greatly expanded funding.13

The limited pace of development for Class B housing emphasizes the need for preservation and rehabilitation strategies of existing and aging US multifamily, a significant portion of which was built in the 1970s and 1980s. In our experience, this is a very stable asset class from an occupancy and turnover perspective, but without sufficient capital directed at preservation strategies, we will see increasing levels of functional obsolescence that further erodes the stock of affordable rentals.

PRIVATE MARKET STRATEGIES A CRITICAL COMPONENT OF HOUSING STABILITY

The US housing market presents a unique landscape where the private sector plays a crucial role in providing and preserving affordable housing. Workforce and affordable rental housing serve as a vital component in addressing the “missing middle”—those households that earn too much to qualify for traditional subsidized housing yet struggle to afford market-rate rents.

In our view, it is crucially important for a stable and sustainable US housing market to have rental housing accessible to a broad swath of the population that is integral to the workforce. Furthermore, from a private sector perspective, we believe that the ability to address missing middle strategies should be a key focus for private investors, not only from the perspective of addressing a systemic shortfall in US multifamily production, but also for desirable investment characteristics.

We view strong demand and stable returns as the hallmarks of private-sector, investment-grade workforce and affordable strategies. One of the defining features that make workforce and affordable rental housing an attractive asset class is the persistent and growing demand for such housing. Economic pressures, including rising housing costs and stagnating wage growth, have only amplified the need for affordable rental options. This demand creates a stable tenant base, reducing vacancy risk and contributing to consistent rental income streams for investors.

Moreover, the performance of workforce and affordable rental housing has proven resilient across economic cycles. During economic downturns, demand often remains robust, as households seek more affordable housing options. This countercyclical nature provides a buffer against broader market volatility, contributing to the asset class’s attractiveness.

For international investors accustomed to deeply subsidized affordable housing models, the US workforce and affordable rental housing sector presents a distinct but equally compelling investment opportunity. Its combination of strong demand and supportive public policies positions it as a robust asset class. As global housing challenges continue to evolve, this sector offers a strategic avenue for investors seeking to target both financial returns and social impact.

NEW: SUMMIT #16

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR: ISSUE #16

Benjamin van Loon, CAE | AFIRE

GLOBAL CONSUMPTION: APAC DATA CENTER INVESTMENT STRATEGIES IN THE AGE OF DIGITIZATION

Michelle Lee, Eugene Seo, and Wayne Teo | CapitaLand Investment

DISTINCT VERTICALS: AI IS CHANGING THE REAL ESTATE INDUSTRY ON TWO DISTINCT PATHS

Daniel Carr and Andrew Peng | Alpaca Real Estate

DIVERGING FORTUNES: ARE COMPARISONS BETWEEN OFFICE AND RETAIL STILL WARRANTED?

Brian Biggs, CFA and Ashton Sein | Grosvenor

OCCUPYING FORCE: INSTITUTIONAL OFFICE PROPERTIES FEELING THE PAIN

Nolan Eyre, Scot Bommarito, and William Maher | RCLCO Fund Advisors

VALUE-ADD VS. CORE: COMPARING CORE AND NON-CORE STRATEGIES WITH NEW DATA

Yizhuo (Wilson) Ding | Related Midwest and Jacques Gordon, PhD | MIT Center for Real Estate

FAVORABLE CONDITIONS: STRUCTURAL CHANGES TO THE MARKET FAVOR NONBANK CRE LENDERS

Mark Fitzgerald, CFA, CAIA, and Jeff Fastov | Affinius Capital

INFRASTRUCTURE VIEWPOINT: INTEREST RATE CHANGES COULD UNLOCK NEW INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENTS

Tania Tsoneva | CBRE Investment Management

MISSING MIDDLE: WORKFORCE AND AFFORDABLE HOUSING IN THE US

Jack Robinson, PhD and Morgan Zollinger | Bridge Investment Group

NARROW SPACES: CHOKED STRAITS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR GDP, INFLATION, AND CRE

Stewart Rubin and Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

OPCO-PROPCO OPPORTUNITY: EMERGING MODELS AND THE KEYS TO STRUCTURING PARTNERSHIPS

Paul Stanton | PTB and Donal Warde | TF Cornerstone

TRANSFORMING LUXURY: UNLOCKING VALUE IN LUXURY HOSPITALITY REAL ESTATE

Alia Peragallo | Beach Enclave and AFIRE Mentorship Fellow, 2024

SOLAR VALUATION: IS SOLAR ENERGY A VALUATION GAME-CHANGER?

David Wei and Michael Conway | SolarKal

GROUND LEVEL: THE CASE FOR GROUND LEASES AND LONG-TERM CAPITAL

Shaun Libou | Raymond James

LEGAL UPDATE / DRIVING FORCE: UNDERSTANDING SYNDICATED LOANS AND MULTI-TIERED FINANCING

Gary A. Goodman, Gregory Fennell, and Jon E. Linder | Dentons

LEGAL UPDATE / ENHANCED PROTECTION: LEVERAGING THE SAFETY ACT FOR ENHANCED LIABILITY PROTECTION IN REAL ESTATE

Andrew J. Weiner, Brian E. Finch, Aimee P. Ghosh, Samantha Sharma, and Sarah Hartman | Pillsbury

+ EDITOR’S NOTE

+ ALL ARTICLES

+ PAST ISSUES

+ LEADERSHIP

+ POLICIES

+ GUIDELINES

+ MEDIA KIT

+ CONTACT

—

NOTES

1. US Census Bureau. “2022 ACS 1-year Estimates.” Census.gov, October 26, 2023. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2022/1-year.html.

2. Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) are a US federal program that incentivizes private developers to create or rehabilitate affordable rental housing for low-income households by providing them with tax credits.

3. Section 8 is a US federal housing assistance program that provides rental subsidies to low-income households, either through vouchers or project-based assistance.

4. AMI determines the thresholds for eligibility to receive housing assistance and can vary widely by market.

5. US Census Bureau. “2022 ACS 1-year Estimates.” Census.gov, October 26, 2023. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2022/1-year.html.

6. Real Page; as of Q2 2024. Minimum income based on industry standard that rends should spend no more than 30% of monthly income on housing costs.

7. US Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, “American Housing Survey (AHS).” Census.gov, February 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs.html. Housing Costs – Renter-occupied Units, created by the AHS Table Creator.

8. US Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, “American Housing Survey (AHS).” Census.gov, February 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs.html. Housing Costs – Renter-occupied Units, created by the AHS Table Creator.

9. US Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, “American Housing Survey (AHS).” Census.gov, February 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs.html. Housing Costs – Renter-occupied Units, created by the AHS Table Creator.

10. National Housing Preservation Database (NHPD). “Picture of Preservation,” May 20, 2024. https://preservationdatabase.org/reports/picture-of-preservation/.

11. CoStar; as of Q2 2024.

12. Engineering New Report via Moody’s Analytics, Baseline Scenario; as of Q2 2024.

13. Will Fischer et al., “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Could Do More to Expand Opportunity for Poor Families,” report, August 2018. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/8-28-18hous.pdf

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jack Robinson, PhD, is Managing Director, Chief Economist and Head of Research; and Morgan Zollinger is Director, Head of Market Research, for Bridge Investment Group.

—

THIS ISSUE OF SUMMIT JOURNAL IS GENEROUSLY SPONSORED BY

Leverage the only investment management suite that automates complex processes and ensures transparency from investor to asset operations, integrating investment and debt management, capital raising, investment, financial, and operational metrics through a branded investor portal. Learn more.