Under the shadow of a slow-burning bank crisis in 2023, should institutional investors consider allocating to short duration real estate debt?

Starting in 2022, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) began the most aggressive policy rate tightening schedule since the early 1980s. The rapid rise in interest rates has left few asset classes unscathed, and public equity and bond returns in 2022, as measured by a variety of benchmarks, were among the worst of the past several decades.

Observers noted that the Fed tends to “hike until something breaks”—an oversimplification that nevertheless resonated following several high-profile bank failures in March 2023. There is no definitive resolution yet to what some have framed as a slow-burning bank crisis.

REALIGINING VALUES

Just as public real estate equity and debt have been impacted by Fed policy rate hikes, private core real estate equity and fixed-rate core real estate debt are experiencing substantial asset value correction. The Gilberto-Levy Index of senior, fixed-rate core mortgage (GL-1) posted a total return of -9.0% in 2022, while the total return for the NCREIF Property Index of core property fell by -3.5%. Both annual performances were the worst in over a decade.

Historically, private real estate debt as an asset class is noted for its depth and stability of income throughout cycles. Recent events have reawakened concerns over the stability of the global financial system, and with each passing moment, it becomes clearer that uncertainty over inflation, monetary policy, and ultimately, asset valuations will take time to resolve. In the meantime, the most significant casualty of the current market environment has been liquidity. Against the backdrop of heightened uncertainty, this article will explore what makes real estate debt—floating rate debt, in particular—well-suited to the structural and cyclical dynamics associated with the current dislocation and its aftermath.

DIMINISHED LIQUIDITY, MATURITY WALL, AND “HIGHER FOR LONGER”

A hallmark of the present dislocation in financial markets is the resilience of the underlying economy. Supply chain disruptions aside, a tight labor market and ample firm and household balance sheets have been a catalyst for spending on wages, goods, and services. The Fed finds itself in a predicament where its two primary mandates of low unemployment and price stability are now in opposition to one another.

Thus far, capital markets have borne the brunt of this policy stance as long-duration asset classes have seen values decline given the intensity of monetary tightening. However, nominal rental growth at the property level has benefitted from real demand growth as well as higher inflation. Though baseline scenarios may have weakened due to concerns over systemic stability, downside scenarios still point to a modest recession relative to historical downturns over the past 25 years. Real estate incomes generally could see manageable impacts even in the event of a recession, given a labor market that has stayed historically tight.

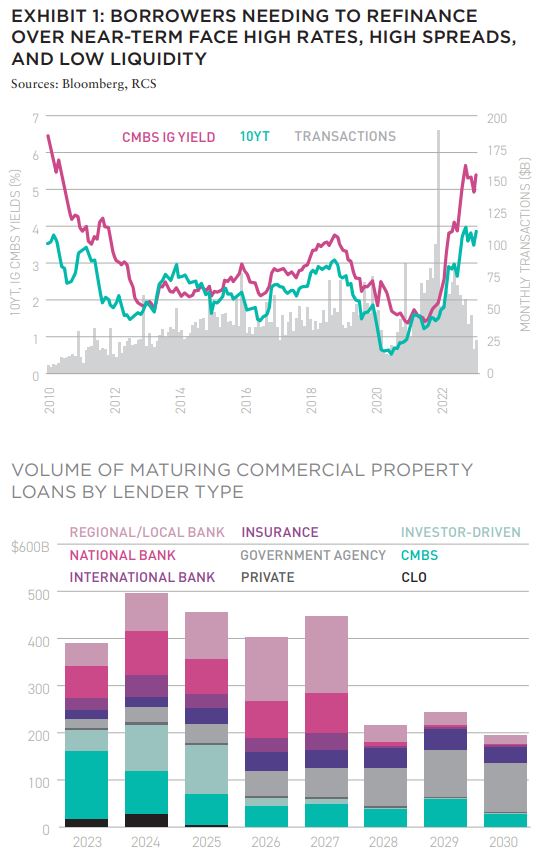

As policy rates and market uncertainty have risen, transactional liquidity has once again bottomed, falling once again to pandemic lows. Commercial mortgage lending standards are tightening in response to an increasing probability of recession. Furthermore, regional banks which have done proportionately more lending in times of dislocation are likely to step back following the highprofile failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank— and the likelihood of greater regulatory scrutiny on banks with less than $250 billion total assets is a primary area of concern.

With base rates higher and sources of capital drying up, borrowing costs rise and demand for leverage declines. However, there is a significant wall of maturity that needs to be refinanced. Some of these loans will not be able to be refinanced without significant paydowns of principal. Some properties that have been significantly impaired due to post-pandemic structural demand shifts, such as “commodity office”, will end as foreclosures or distressed sales. While delinquencies and defaults are currently low, they are likely to rise. Borrowers have tried to “kick the can” when they could, finding temporary workarounds to stave off foreclosure and hoping for transaction activity to normalize. That strategy was passable when the Fed was accommodative, but much less so now that the FOMC has repeatedly communicated that it needs to keep its policy rate “higher for longer” in order to quash inflation and drive out speculative investment fostered by a decade of inexpensive debt.

REAWAKENING TO DURATION RISK

Declining interest rates over the past four decades have been a tailwind to refinancing. Accelerated inflation has forced the Fed to raise policy rates above their zero bound, causing bonds and bondlike instruments with long durations to fall in value. Duration risk measures the sensitivity of a bond’s price to changes in the underlying rate. SVB’s sudden failure was tied to duration risk. When the bank attempted to sell some of its holdings of long-dated US Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, the mark-to-market effect exposed SVB’s capital base to a dramatic decline in the value of its fixed income portfolio directly related to tighter monetary policy. Since SVB’s failure, emergency public sector measures have been implemented to provide banks with liquidity.

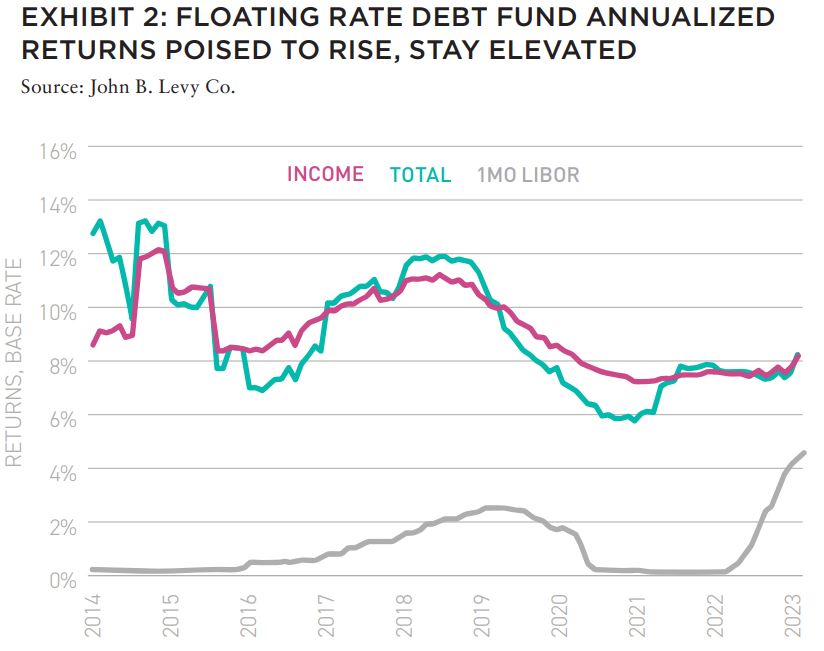

Interest rate volatility and spiking policy rates have reawakened investors to the duration risk embedded within their portfolios. When interest rates are low, the impact of duration risk is amplified. Floating rate debt minimizes duration risk, although lenders are exposed to a decline in interest rates, which forward curves anticipate. When liquidity is scarce and an economic recession is an increasingly more likely proposition, lenders can charge higher spreads over reference rates. The persistence of inflation is weaning borrowers off their expectations that interest rates will soon normalize at a lower level. Even after the Fed lowers its policy rate as price pressures are gradually contained, investors have realized that risk premiums should be higher going forward. When appropriately structured, floating rate real estate debt has demonstrated a durable income stream coupled with a meaningful illiquidity premium, which is uniquely suited for periods of elevated volatility.

CONSTRUCTION NEEDED

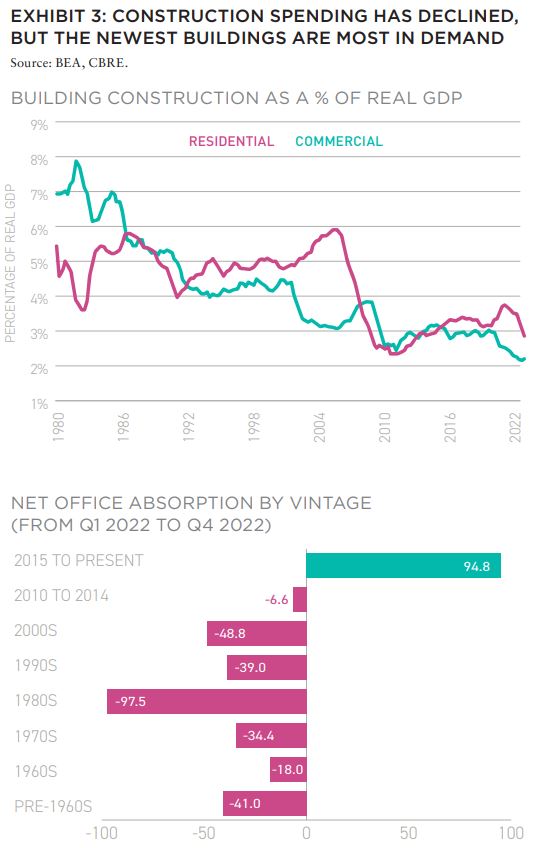

Building construction encompasses a variety of risks including regulatory, counterparty, capital markets, and event risks. Even during the best of times, real estate development is a highly complex endeavor. Surging labor and materials prices and supply chain disruptions have wreaked havoc on construction budgets and timelines. Yet, as a percentage of real GDP, both residential and non-commercial structures investment is at multi-year lows. The presently depressed level of real estate construction will not address the varied, secular demand tailwinds most readers are familiar with. Numerous themes including undersupply of rental residential, onshoring/re-shoring, green buildings, and post-pandemic STEM offices have been explored in depth by various authors in this publication. The scale of these opportunities is massive— to raise construction activity to its long-run historical average percentage of GDP would mean almost $700 billion of additional investment over the past five years.1

Construction lending can provide risk-mitigated exposure at significantly higher spreads relative to publicly traded bonds. Elevated project costs have actually been a headwind for development. The case for replacing or readapting the US’ aging building stock is clear. In the current environment, a loan’s spread is locked as uncertainty remains high and debt funding remains scarce, but funds over the next few years as both macro and project-specific risks diminish. Anecdotally, project costs have stabilized allowing planners more clarity over the near term. If the case for a modest recession plays out, then construction or redevelopment projects beginning now could deliver into a tenant demand recovery.

NO EASY SOLUTIONS FOR WHAT LIES AHEAD

Following a 40-year “bond bull market” characterized by falling debt costs, we may be entering a new inflation and interest rate regime—the effects of which have already been severe to say nothing of what lies ahead. Investing during moments of dislocation and volatility is easier in theory than in practice. Importantly, while there are asset classes like real estate debt that are better suited for the deployment of capital during volatile and uncertain periods, they are neither antidotes to nor insulated from the potentially momentous impacts that a change from “lower for longer” to “higher for longer” will have on asset values, debt costs, and risk tolerance over the medium term. Furthermore, broad segments of the economy remain highly resource constrained. Infrastructure projects, for example, have pulled away labor from private construction projects.

Private lenders including real estate debt capital providers have relied heavily on portfolio leverage usually in the form of credit and/or loan facilities in order to achieve their target returns. Until recently, these were available at accretive borrowing costs. Certain real estate lenders have found themselves squeezed both by the lack of borrower demand for more expensive debt and reduced availability of portfolio leverage at an accretive rate, although higher base rates and lending spreads have eased the dependence upon additional leverage.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dags Chen, CFA, is Managing Director and Head of U.S. Real Estate Research and Strategy for Barings Real Estate, a global real estate platform with extensive capabilities across both debt and equity strategies.

NOTES

1. Source: BEA, Barings Real Estate Research. As of Q4 2022.

—

EXLORE THE FULL ISSUE

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

AFIRE INTERNATIONAL INVESTOR SURVEY: Q1 2023 PULSE REPORT

Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

VALUATION CHALLENGE: SOLVING THE CRISIS IN COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE VALUATION

Matt Pomeroy, MAI and Jackie Bowie | Chatham Financial

CONVERSION CALCULATOR: LEGAL OR NOT, A DYNAMIC CITY WILL CONVERT UNUSED OFFICES

Jim Costello | MSCI Real Assets

UNDERWRITING ROADBLOCKS: CAN THE HOSPITALITY MODEL OF UNDERWRITING SAVE OFFICE VALUES?

Joshua Harris, PhD | Lakemont Group & Fordham University

VACANT SPACE: OFFICE-USING JOBS AND DEMAND INCONGRUITY

Stewart Rubin and Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

HIKING TRAILS: SHOULD INVESTORS CONSIDER ALLOCATIONS TO FLOATING-RATE DEBT?

Dags Chen, CFA | Barings Real Estate

RECESSION PREPPING: HOW VULNERABLE ARE COMMERCIAL MORTGAGE INVESTMENTS

Martha Peyton, PhD | Aegon Asset Management

MEASURING GENTRIFICATION: USING DATA SCIENCE TO PREDICT THE IMPACTS OF GENTRIFICATION

Ron Bekkerman | Cherre + Donal Warde | Tenney 110 + Maxime C. Cohen | McGill University

THE FUTURE IS EUROPEAN: THEMES FROM THE OLD WORLD SHAPING US MARKETS

Brian Klinksiek | LaSalle Investment Management

CULTURE SHOCK: THE CHALLENGE AND IMPORTANCE OF TRANSLATING ESG ACROSS BORDERS

AFIRE ESG Committee

FINE TUNING: GLOBAL REACH AND LOCAL EXPERTISE CAN CREATE UNIFIED REAL ESTATE EXPERIENCES

Mark Zettl | JLL

ACCESSING SUCCES: EXPLORING DIVERSITY TRENDS IN REAL ESTATE TALENT

Zoe Huges | NAREIM

RESCUE CAPITAL: RESPONDING TO THE NEW REAL ESTATE REALITY

Andrew Weiner and Joshua M. R. Becker | Pillsbury

CONVEX CURVES: A REMINDER ON PRICE CONVEXIVITY AND CAP-RATE VOLATILITY

Joseph Pagliari, PhD, CFA, CPA | University of Chicago

IN MEMORIAM: ANDREA MARIE CHEGUT, PhD, MIT