The pandemic-driven changes to downtown areas and central business districts are changing the geography of institutional investment. What else changes because of this?

As the US continues to muddle through the COVID-19 pandemic, downtowns and central business districts (CBDs) have emerged as the urban and metropolitan geographies most vulnerable to structural changes in where and how Americans work.

By all accounts, the rise of remote work and the broadening of the term “flexible work” appear to be permanent rather than temporary phenomena; structural rather than cyclical. It is now commonplace to acknowledge that the loss of office workers— and prospect of empty office buildings—threatens the long-term fiscal health of many cities, the small businesses that depend on office workers, and the vitality of America’s downtowns.

The “evidence” from a pandemic still underway paints a disruptive future. The McKinsey Global Institute’s “Future of Work After COVID-19” report estimates that 20–25% of the workforce could work remotely in the future.1 A plethora of media articles and business surveys report how companies large and small are embracing hybrid work models, enabling their employees to work remotely part of the time. A recent article from the New York Times—“Why the Empire State Building, and New York, May Never Be the Same”2—is the common meme for business and general media alike; just change the moniker of the building and the name of the city and you get the emerging conventional wisdom.

As institutional investors struggle to make sense of these shifting dynamics, it is best to look beyond the simplicity of shock headlines and re-discover the complexities that define America’s downtowns as well as other urban and suburban districts which increasingly combine a mix of uses including work, residential, education, research, commercialization, entertainment, waterfront or other amenities, and distinctive retail and restaurant choices— uses typically associated with downtown areas.

Such an inquiry forces investors to look at the distinctive market realities that define individual US downtowns rather than group all downtowns (particularly those located in a small subset of cities) in one narrowly drawn asset class. The end result may be that the pandemic may compel an expansion of institutional investment to a broader set of uses and geographies in a broader set of cities.

DOWNTOWNS ARE NOT UNIFORM

Despite a common label, America’s downtowns are an intensely varied group of similarly situated districts. As the New York Times recently reported, the share of downtowns that is occupied by office uses varies from 83% in Boston, 74% in San Francisco, and 72% in Washington, DC to 30% in Nashville, 25% in St. Petersburg, and 19% in San Diego.3 Most downtowns in the country have undergone a dramatic transformation over the past sixty years; first, radical decline as populations suburbanized and employment decentralized, then, rebound and revival fueled by shifting location preferences, changing cultural dynamics, and declining crime. As Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui recently wrote:

“Downtowns, like investment portfolios, are more sustainable when they are diverse. [. . .] CoStar data going back to 2006 shows that many big-city downtowns have been evolving away from strictly offi ce space, adding college dorms, apartment buildings, and civic attractions. Cities where ‘downtown’ has increasingly come to mean more than offices are likely to be more resilient as they emerge from the pandemic, researchers and downtown officials say.”4

Targeted public, philanthropic, corporate, and university investment has also played an enormous role in the transformation of downtowns over the decades. Dan Gilbert’s decision to move Quicken Loans (and his family of companies) to the core of downtown Detroit in 2007 started a revival that continues to this day. Duke University is widely credited with acting as the stimulus for the rebirth of downtown Durham; the same can be said of Arizona State University in downtown Phoenix. Similar moves by local investors can be found in downtowns as disparate as Cincinnati, Cleveland, Erie, St. Louis, and Tampa.5

THE RISE OF INNOVATION DISTRICTS

Downtowns are not the only geography of employment density in cities and metropolitan areas. Over the past twenty years, innovation districts have organically emerged near advanced research institutions and health care centers. The Brookings Institution defines these districts as:

“Geographic areas where leading-edge anchor institutions and companies cluster and connect with start-ups, business incubators, and accelerators. They are also physically compact, transit-accessible, technically wired, and offer mixed-use housing, office, and retail.”6

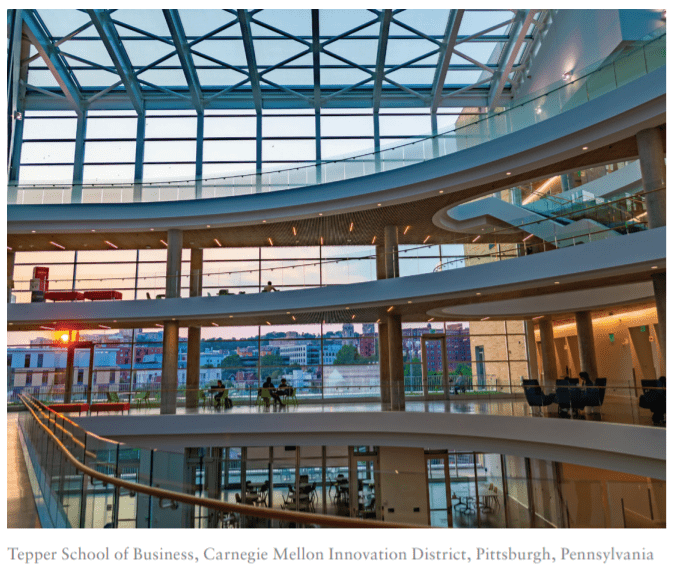

These districts reflect the innovation economy’s demand for colocation, proximity, and density so that companies, researchers, and entrepreneurs can share ideas rather than invent in isolation. It is doubtful that the pandemic has disrupted the innovation dividend associated with such co-location. The most advanced districts are in midtown areas such as Midtown Atlanta (near Georgia Tech), University City in Philadelphia (near Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania), and Cortex in St. Louis (a collaboration of Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis University, and Washington University). However, the un-anchoring of anchor institutions such as Duke University and Arizona State University, described above, shows that “traditional” downtowns have the potential to evolve as innovation districts.

FEDERAL POLICY MATTERS

Downtowns have the potential to harness unprecedented federal investments to mitigate the damage from the pandemic and accelerate the transition to a multi-use future. The federal government is engaged in a multi-act, multi-dimensional effort to spur an equitable economic recovery. The US$1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan enacted in March 2021, for example, provides fl exible funds to states, cities, and counties (as well as resources via the Department of Treasury, Small Business Administration, and Economic Development Administration) that can be used to rebuild downtown economies and promote business and neighborhood equity.

Other moving or proposed legislative vehicles go even further. The US$250 billion Innovation and Competition Act, passed with bipartisan votes by the US Senate, would provide resources to expand basic and applied research, STEM education, and technology hubs. A US$1 trillion+ infrastructure bill, also passed with bipartisan support by the US Senate, recommends unprecedented investments in a broad array of infrastructure assets including: transportation (e.g., roads and bridges, public transit, passenger and freight railways, airports, waterways, and ports), buildings and utilities (e.g., affordable housing, high speed broadband, electric grid, public schools), and disaster resilience.

These investments are on top of existing federal programs, such as Historic Preservation Tax Credits, Low Income Housing Tax Credits, New Market Tax Credits, and Opportunity Zones, which have historically been used to diversify uses within downtowns.

As federal legislation proceeds, there are even efforts to focus federal investments directly on downtown disruption. In an effort to revitalize downtown business and urban districts, Senators Debbie Stabenow (D– MI) and Gary Peters (D–MI), along with Representatives Jimmy Gomez (D-CA), Dan Kildee (D-MI), and John Larson (D-CT) have introduced the Revitalizing Downtowns Act. Modeled after the Historic Tax Credit, the Revitalizing Downtowns Act would provide a credit equal to 20% of the Qualified Conversion Expenses in converting obsolete office buildings into residential, institutional, hotel, or mixed-use properties. An obsolete office structure is defined as a building that is at least twenty-five years old, and the bill requires 20% of the units in a residential conversion to be dedicated to affordable housing.

STATE AND LOCAL POLICY MATTERS

Beyond federal investments, states and municipalities also have a role to play through incentive programs such as TIF districts, tax abatements, and PILOT programs, all of which can be utilized to help downtowns and other urban districts rebound from pandemic disruption. Many states and localities, in particular, have specific programs to assist with adaptive reuse of historic structures. For example, North Carolina’s Mill Credit program made it feasible to redevelop 1.2 million SF of former R.J. Reynolds Tobacco factory buildings in Winston-Salem, thereby preserving these beautiful buildings while providing a unique sense of place for the Innovation Quarter. Similar programs have been successfully employed in Durham, NC; Providence, RI; Pittsburgh, PA; and Cleveland, OH.

WHAT THIS ALL MEANS

The COVID-19 pandemic could have major implications for institutional investments in downtowns and CBDs. Pre-crisis, these investments tended to be over-concentrated in a narrow group of asset classes in a small subset of US cities.

Post-crisis market dynamics should place a premium on downtowns and other parts of cities that have a broader mix of uses and activities, including innovation-oriented co-location of research institutions, mature companies, and start-ups and scale ups. In doing so, investors would be wise to examine the “good bones” of downtowns in secondary and tertiary cities that have not been the traditional focus of institutional investment. Investors should also track the flow of federal investments that are likely to leverage the distinctive competitive assets and advantages of these places. This will require a commitment to robust market analysis that captures the full growth potential of a broad, geographically diverse set of CBDs, and effectively reimagine the future of “downtown.”

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Frances Kern Mennone is Managing Director for FBT Project Finance Advisors, a registered municipal advisor.

—

NOTES

1Susan L., Anu M., James M., Sven S., Kweilin E., and Olivia R., “The Future of Work After COVID-19,” McKinsey Global Institute (2021), https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19

2Keith Collins, Nikolas Diamant, Peter Eavis, Or Fleisher, Matthew Haag, Barbara Harvey, Lingdong Huang, Karthik Patanjali, Miles Peyton, and Rumsey Taylor, “Why the Empire State Building, and New York, May Never Be the Same,” New York Times, September 15, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/09/15/nyregion/empirestate-building-reopening-new-york.html (Accessed September 25, 2021).

3Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui, “The Downtown Offi ce District Was Vulnerable. Even Before Covid,” New York Times, July 7, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/ interactive/2021/07/07/upshot/downtown-offi ce-vulnerable-even-before-covid.html (Accessed July 12, 2021).

4Badger, “The Downtown Offi ce District Was Vulnerable. Even Before Covid.”

5See Also: Bruce Katz, Jennifer S. Vey, and Julie Wagner, “One Year After: Observations on the Rise of Innovation Districts,” Brookings Institution, 2015, https://www.brookings. edu/research/one-year-after-observations-on-the-rise-of-innovation-districts/; Bruce Katz, Karen Black, and Luise Noring, “Cinncinati’s Over-the-Rhine,” Nowak Metro Finance Lab, 2019, https://drexel.edu/nowak-lab/publications/case-studies/cincinnati-city-case/; Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley, The Metropolitan Revolution: How Cities and Metros are Fixing Our Broken Politics and Fragile Economy (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2014).

6Bruce Katz and Julie Wagner, “The Rise of Innovation Districts: A New Geography of Innovation in America,” Brookings Institution, June 1, 2009, https://www.brookings.edu/ essay/rise-of-innovation-districts/

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE (FALL 2021)

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR / GROUPTHINK VS. GROUP COLLABORATION

AFIRE | Benjamin van Loon

MID-YEAR SURVEY / CHECKING THE PULSE

No matter your age or experience, 2021 has shaped up to be a year that no one can forget. Findings from the AFIRE 2021 Mid-Year Pulse Survey detail a cautious road ahead.

AFIRE | Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon

CLIMATE CHANGE / REASSESSING CLIMATE RISK

The commercial real estate industry may not yet fully grasp the actual relationship between climate risk and asset pricing and value. But the knowledge is coming fast.

York University | Jim Clayton

University of Reading | Steven Devaney and Jorn Van de Wetering

Kinston University | Sarah Sayce

UNEP FI | Matthew Ulterino

NON-TRADITIONAL / THE ALLURE OF SPECIALTY SECTORS

Real estate investments have historically coalesced around common property types—but it may make sense for investors to reconsider specialty property sectors in the post-COVID world.

Invesco Real Estate | David Wertheim

NON-TRADITIONAL / NON-TRADITIONAL IS GOING MAINSTREAM

The mainstreaming of nontraditional property types is well on its way within institutional investing, which will materially broaden the real estate investment universe.

Principal Real Estate Investors | Indraneel Karlekar, PhD

DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE / DIVERSIFYING INTO DIGITAL

As investors look for sustainable sources of inflation-protected yield, real estate investment is increasingly blurring into a wider range of “digital” real asset investment strategies.

AECOM Capital | Warren Wachsberger, Josh Katzin, and Corbett Kruse

LIFE SCIENCES / TAPPING INTO BIOTECH

Over the past two decades, the single-family rental industry haLife sciences real estate has been a “hot” property type for the past decade—and even more since the pandemic. Will all the capital targeting the space be placed where it needs to go?

RCLCO | William Maher, Ben Maslan, and Cecilia Galliani

ESG + CLIMATE CHANGE / HIGH-WATER MARKS

Interest and excellence in ESG performance is becoming increasingly critical to portfolio strategy. So with sea levels on the rise, how can portfolios stay above water?

Barings Real Estate | Jerry Speltz

ESG + NET-ZERO / VALUING NET-ZERO

With more tenants focusing on environmental targets, the burden to reduce direct emissions places increased pressure on investors, who are at a pivotal moment in ESG strategy.

JLL | Lori Mabardi, Emily Chadwick, and Eric Enloe

ESG + FAMILY OFFICE / FAMILY OFFICES AND ESG

As sustainable investing continues to grow in popularity, family offices have taken note—and understanding ESG targets and regulations will be key for longterm performance.

Squire Patton Boggs | Kate Pennartz and Rebekah Singh

DEBT / WHY DEBT, WHY NOW?

Debt funds remain a comparatively small part of the real estate investment market, but they have been gaining in prominence in recent years.

USAA Real Estate | Karen Martinus, Mark Fitzgerald, CFA, and Will McIntosh, PhD

MIGRATION / MIGRATION IN REAL TIME

As the public health situation started to improve in early 2021 and the economy reopened, did migration flows change too—and what if we are able to answer this in real time?

Berkshire Residential Investments | Gleb Nechayev

StratoDem Analytics | Michael Clawar

URBANISM / DOWNTOWN DISRUPTION

The pandemic-driven changes to downtown areas and central business districts is changing the geography of institutional investment. What else changes because of this?

Drexel University | Bruce Katz

FBT Project Finance Advisors + Right2Win Cities | Frances Kern Mennone

WORK-FROM-HOME / CHOOSING FLEXIBILITY

Employees are increasingly demanding flexibility and choice for where (and when) they work. What strategies can landlords implement to adapt?

Union Investment Real Estate | Tal Peri

TALENT AND RECRUITMENT / TALENT PARITY

To be better prepared for future risks, firms need diverse talent. So is the goal of 50% female representation achievable in global real estate investment and asset management firms?

Sheffield Haworth | Isabel Ruiz

CLIMATE CHANGE / PREDICTING THE CLIMATE FUTURE

We are all invested in the cities, assets, and infrastructure of tomorrow, even if we might not live to see the ten largest cities in 2100. But understanding climate change can get us closer.

Climate Core Capital | Rajeev Ranade and Owen Woolcock