SITUATED BETWEEN SOME OF MANHATTAN’S MOST SOUGHT-AFTER NEIGHBORHOODS – WEST VILLAGE, SOHO AND TRIBECA – HUDSON SQUARE IS POISED TO BE THE NEXT ICONIC NEIGHBORHOOD IN NEW YORK CITY AFTER BEING LONG OVERLOOKED AS PRIMARILY A MANUFACTURING DISTRICT.

In 2015, Norges Bank entered into a joint venture (JV) with Trinity Church Wall Street, the historic Episcopal parish church in downtown Manhattan, to provide the crucial restoration, renovation, and renewal investment to transform Hudson Square into the new creative edge of New York City.

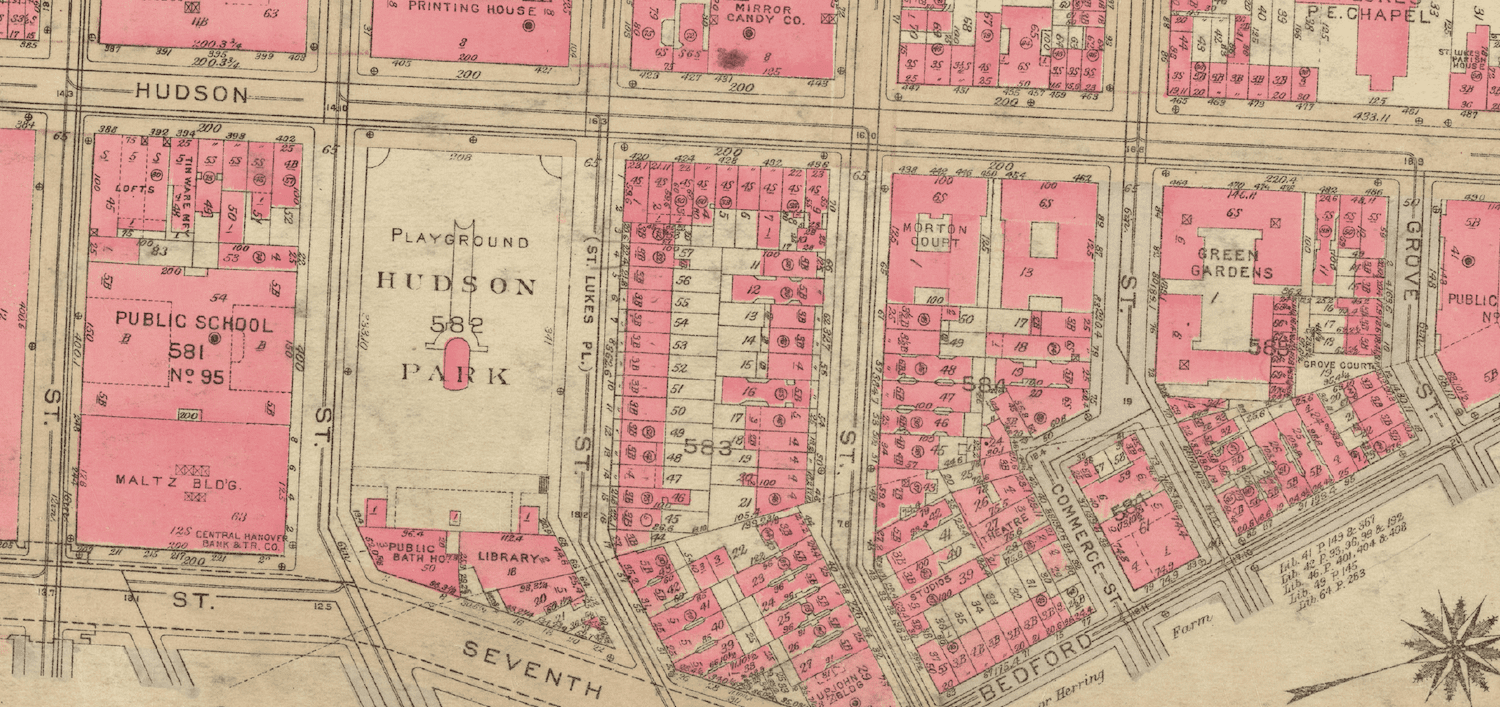

THE HISTORY OF HUDSON SQUARE

Trinity Church was founded in 1697 when the Crown leased land known as King’s Farm to Trinity for “60 bushells of winter wheat [sic].” Almost a decade later, in 1705, Queen Anne fully gifted the land to Trinity Church, beginning the story of one of Manhattan’s largest landowners.

The area now known as Hudson Square has, over time, housed the Mansion in King’s Farm, George Washington’s headquarters, which later was owned by Aaron Burr, Vice President under Thomas Jefferson, and American businessman John Jacob Astor.1 In 1802, Hudson Square became the city’s first private park development and Trinity introduced 99-year residential leases to the neighborhood. By the late 19th century, Hudson Square had developed into a commercial center known as the Printing District, the epicenter of new ideas and communication.

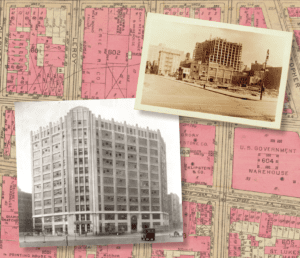

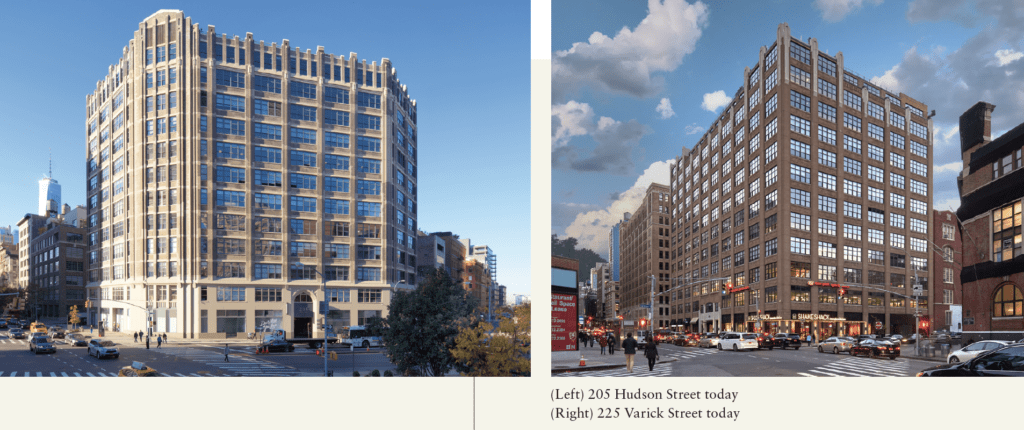

Most of the buildings that came to be constructed within the JV’s 6 million square foot portfolio—featuring vast open floorplates and strong structures—were constructed to accommodate heavy commercial printing equipment and industry. With the eventual decline of the printing medium, these spaces were repositioned as lower-rent offices and storage units, until a small community of creative tenants, such as architects, independent advertising agencies, boutique investment fi rms, and others, became drawn to the authentic heritage of the neighborhood and pioneered the movement to the West Side.

Hudson Square has since become renowned for its commercial and retail tenancy, consisting of thought-leaders and idea-generators such as Google, Disney, Publicis, Warby Parker, TED, and Squarespace, all of which are fi nding inspiration in the area’s historic buildings and are shaping the future of business and culture today and for years to come.

TRANSACTION THESIS

The formation of the joint venture between Norges and Trinity in 2015 was a long process that began when, rather than bidding for 100% of four assets as marketed, Norges Bank placed a bid for 48% of 11 assets. Since the original transaction in 2015, the venture has expanded through the acquisition of 375 Hudson in 2017, and the forward purchase of two development sites in 2019.

From the outset, the business plan was to bring Hudson Square to an equal perceptual footing with West Village, Soho, and Tribeca by repositioning existing stock, developing vacant land, and upgrading and increasing the retail offering. On top of the venture developments, the joint venture also supported residential development that has paved the way for more mixed-use activity and has further increased the appeal of Hudson Square as a dynamic, around-the-clock community centered around its creative tenancy.

ORIGINAL USE AND ATTRIBUTES OF THE HUDSON SQUARE ASSETS

The buildings within Hudson Square, largely constructed in the 1920’s, were predominately built to cater to the printing industry. They were designed to carry a heavy weight load, as printing presses utilized into the 1930’s weighed in at a few tons. As a result, the floor load capacity in most of the current assets is 200-250 pounds per square foot, compared to a modern office load capacity of 50 pounds per square foot.

The framing structures are reinforced concrete with ceiling heights upwards of 13 feet, and the buildings range from 12 to 17 stories tall. Because these buildings stand taller next to lower-height buildings in the West Village, they offer a scenic protected view corridor. The largest assets are roughly 1 million square feet each, while the smallest stands at 60,000 square feet, and most structures had large floorplates but inactivated roofs at the time of purchase. Aside from the high ceilings, the assets also featured large windows and nicely shaped mushroom shaped columns.

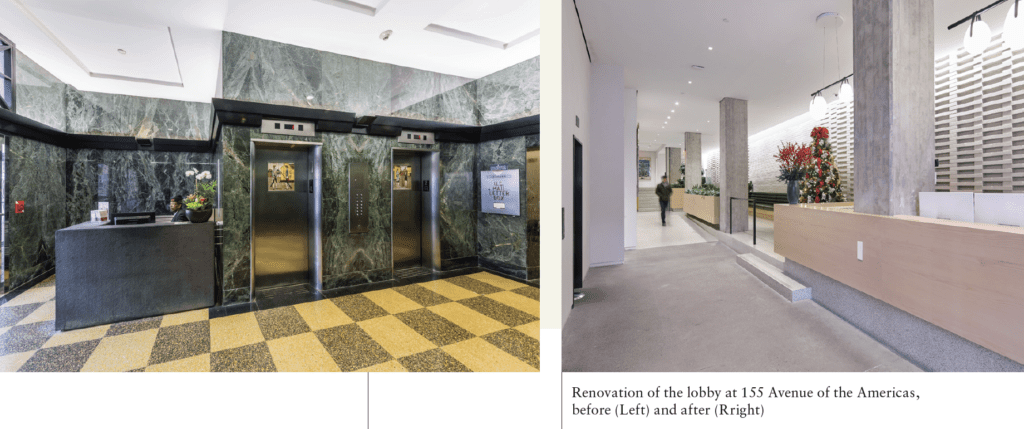

REPOSITIONING THE ASSETS

At the time of acquisition, most of the assets were in need of a refresh to varying degrees. Consistent with the business plan of the JV, these buildings were programmatically repositioned with a common goal— to enhance tenant productivity and creativity, starting with activated rooftops and lobbies in each building. In fact, recent leasing has been contingent on both in order to achieve the rent levels set out in the business plans. The roofs serve both as private and recreational space, providing siting for building-wide amenities, while the new lobbies include retail offerings and lounge seating.

As the original structures are strong and able to carry more weight than required by modern office users, slab openings have been created in some buildings to connect multi-level tenant spaces, allowing for improved internal occupier circulation as well as interesting multifloor gathering spaces for town halls and staging for group events that can reinforce community.

Most of the recent leasing activity has also been centered around technology, advertising, media, and information (TAMI) tenants, who seek collaborative, large-floorplate layouts that allow for efficient space use and open floorplan design, making Hudson Square buildings ideal working environments.

PORTFOLIO LOCATION AND USAGE OVER TIME

The twelve buildings are mostly located along the Hudson Street corridor ranging from Canal Street in the south to Morton Street in the north. The buildings are primarily focused within two clusters: one at the intersection of Canal and Hudson; the second at the intersection of Houston Street and Hudson. In this way, the portfolio is ideally located at the crossroads of West Village to the north and Tribeca to the south, with several additional assets located along 6th Avenue along the border of Soho.

The clustering of the portfolio has allowed the JV to offer flexible and scalable office space solutions to tenants looking to grow, contract, or relocate within the neighborhood as their business needs change over time.

The portfolio also includes almost 200,000 square feet of retail space across its existing 12 commercial buildings. A variety of users call Hudson Square home, including well-known retailers such as Shake Shack, Dig Inn, Essen, and Starbucks, alongside smaller, creative tenants such as Blue Bottle, Chillhouse, and Ducati. As the Hudson Square area continues to grow, the JV is focused on bringing retail to its buildings not only for its own portfolio, but to strengthen the neighborhood cohesion of Hudson Square.

NEIGHBORHOOD EVOLUTION

The Hudson Square renaissance is transforming the once quiet neighborhood into a dynamic and creative 24/7 community. No longer overlooked, Hudson Square’s deep roots and unique location between some of the most sought-after neighborhoods in Manhattan has led to incredible growth in the neighborhood without compromising its authentic history. Facilitated by the Hudson Square Properties JV (Trinity Church, Hines, and Norges Bank), along with many other landlords and companies, the neighborhood has seen a surge in investment and restoration that has elevated Hudson Square to become one of the strongest office submarkets in New York.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

David Roll is Portfolio Manager and Grayson Hoffmann is an Investment Manager at Norges Bank Investment Management, the asset management unit of the Norwegian central bank, tasked with managing the Government Pension Fund Global.

NOTES

1. The correlation between Burr and Astor traces back to Burr’s duel with former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in 1804. Held as the culmination of a longstanding feud between the two statesman, Hamilton died from a bullet wound after the duel, and Burr fl ed to the south to escape negative sentiment against him in New York. In his leave, his creditors (to which he was materially indebted) seized his assets, sold his furniture, and sold his Richmond Hill estate (located within the King’s Farm area) to Astor, who would ultimately subdivide it and build more homes, some of which still exist today. The transfer would likely have never happened if Burr did not kill Hamilton.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN SUMMIT (SPRING 2020)

—