This article appears in Summit Journal (Fall 2020) | Download PDF |

The cliché that crisis reveals character is usually stated in relation to standalone events. But what happens to character when the crisis stretches beyond a moment?

It seems like years rather than months ago, but if we look back to early 2020, conditions in real estate markets, particularly for value-add deals, were healthy, and arguably even approaching frothy territory in some spots. Investor demand outweighed the supply of transactions, and core investors dipped into value-add territory seeking incremental returns.

By the time this article is published, it will have been nearly a year since COVID-19 first spilled into the human population. Today, millions of cases have spread across the world; more than a million have died; millions more now suffer from long-term conditions, and economies and civil balances around the world are on thin ice. The pandemic has tested character at all levels—personal, relational, organizational, national, and political.

That the pandemic become so rife and prolonged has not only revealed each person’s character, for better or for worse, but it has also elevated typically subconscious social and ethical behaviors into the realm of everyday discourse. Whereas the measured ethical intentions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles have emerged as the de facto conscience of corporate behavior over the past decade, mounting civil unrest, racial tensions, and economic inequality have forced business leaders and organizations to face fundamental ethical questions once politely reserved for elective college courses.

In this brave new world, mere compliance with standards is not enough for an organization to bolster its reputation and maintain the trust of its stakeholders and customers. Values are not an afterthought. Determining the values that matter, as well as specific behaviors that accompany those values—and the degree to which those values can guide difficult decisions—is of greater importance now as we stand at the intersection of economic opportunity and existential necessity.

Right now is when organizations have both the time and the need to take ethics seriously. As noted by Kelly, McGowan, and Norris in the February 2020 of Real Estate Issues, “without a command of the ethical vocabulary that is being presumed in the discussion, without a thoughtful study of the concepts expressed in that vocabulary, and without the ability to make a critical judgment about the applicability of such concepts, such an executive is ill-equipped to make, explain, and carry out basic leadership functions.”[1]

In other words, without an ethical vocabulary, and the organizational prioritization to understand that vocabulary—especially during the crisis—businesses can get sick too. And some might disappear entirely.

Philosophically, it would be difficult to reject the importance of good ethics, but ethical clarity often becomes obscured when aspirations meet reality. While the corporate principles of transparency, loyalty, and service are touted as core ethical values, the struggle—belied by the dozens of ethical codes and certifications circulating in our trade—is to define what these principles look like in practice.

In his essay, “Craving the Light,” also published in Summit Journal, G. Andrews Smith, advanced the conversation a bit farther towards practicality for investment managers. He posits that now—especially in the era of COVID-19—”Being intentional and open in our dealings with investors, employees, and communities will bring closeness to all our relationships—particularly those between managers and investors.”[3]

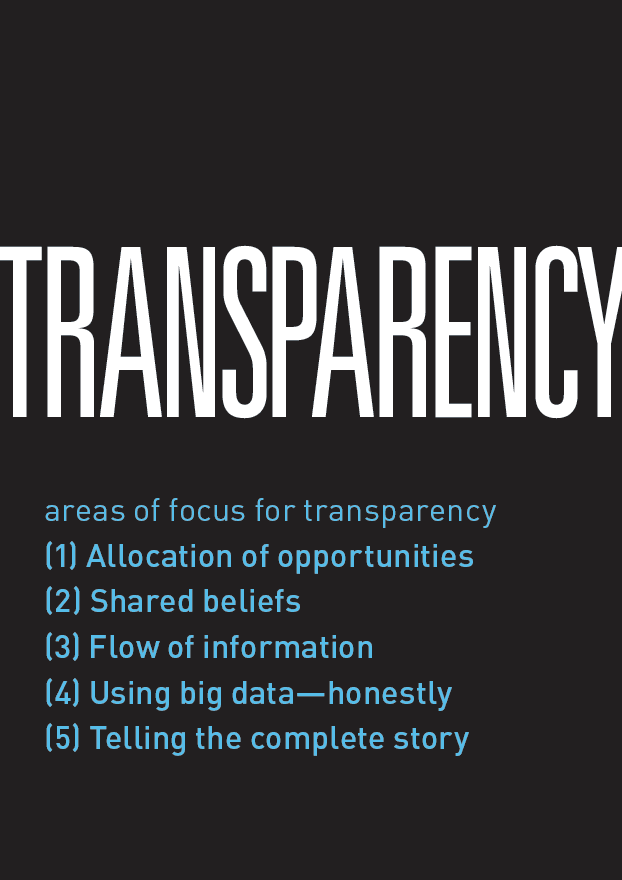

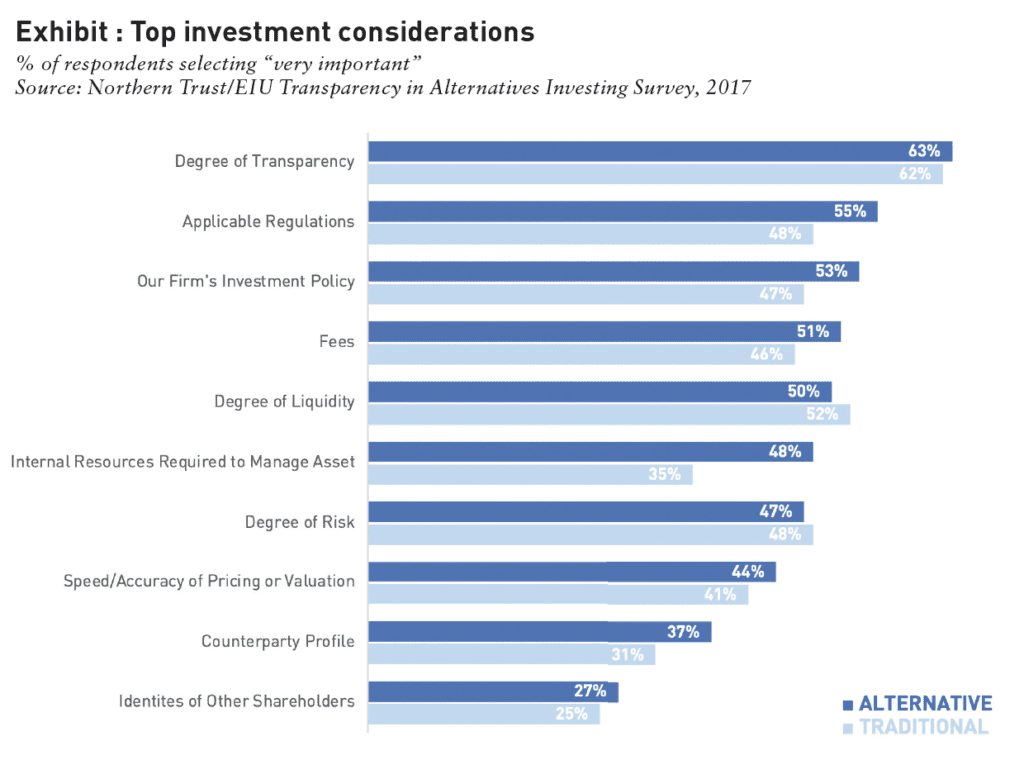

According to a 2017 report from the Economist Intelligence Unit focused on investor considerations for alternative investing, respondents ranked transparency as the top priority for both alternative and traditional investing considerations, followed by regulation, policies, and other factors.[4] With these priorities in mind, Smith proposed five examples of what transparency looks like in practice, regarding (1) allocation of opportunities, (2) shared beliefs, (3) flow of information, (4) using big data—honestly, and (5) telling the complete story. In summary, Smith says, managers whose dealings are grounded in transparent practices will be better positioned to deliver better investments.

But the truth underscoring the practice of transparency can be elusive when it confronts the politics and dynamics of personal and organizational relationships fundamental to our industry.

To shed light on this dynamic, AFIRE held its first-ever Ethics Summit in October 2020, led by the James B. Duke Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Economics at Duke University, Dan Ariely. As the New York Times bestselling author of The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty, The Upside of Irrationality and other groundbreaking books in behavioral economics, Ariely focuses on the connection between behavior and ethicality.

Core to Ariely’s ideas is the specter of the “slippery slope”, or the notion that one small lie can lead to steady and often unconscious increases in egregious and amoral decision-making, a la Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos. As he writes in The (Honest) Truth, “Understanding how slippery slopes operate can direct us to pay more attention to early cases of transgression and help us apply the brakes before it’s too late.”[5]

Much of the behaviors in finance and investing were built over decades of best practices and behavioral algorithms. Routine has its own way of obfuscating ethical awareness, and an overreliance on habit contributed to the Great Financial Crisis in the early 2000’s. In the following years, organizations took social responsibility much more seriously. “In response to this man-made disaster,” Ariely says, “we’ve taken some steps toward coming to terms with some of our irrational tendencies, and we’ve begun reevaluating our approach to markets accordingly. The temple of rationality has been shaken, and with our improved understanding of irrationality we should be able to rethink and reinvent new kinds of structures that will ultimately help us avoid such crises in the future. If we don’t do this, it will have been a wasted crisis.”[6]

While some organizations, particularly among AFIRE membership, are leaders in corporate responsibility (in accordance with these charges of overcoming irrationality and defying the slippery slope), the COVID-19 crisis and impending long-term economic damages have thrust the real estate and financial industries into the limelight. Economic livelihoods aren’t the only things at stake. During a pandemic—especially one dominated by an airborne, transmissible, and deadly disease that spreads most easily indoors—people’s lives could be lost if we rely on the amoral comforts of routine.

FIGHTING THE ROUTINE

AFIRE will foster these conversations through ongoing virtual events and forums, as well a series of case studies (as in the study on the following page) designed to assess ethical behavior for real estate, communities, and the unpredictable post-pandemic world.

Ethics are dynamic. There is no one moment where a person or organization becomes ethical. Ethics are dialogical, which is precisely what makes them easy to overlook. Ethics take constant work; balancing and re-balancing social behaviors (per Ariely), institutional responsibilities, and personal values against the mercurial expectations of everyday life. This is precisely why it’s easy to let habituation and routine replace ethical consciousness, because if something worked okay yesterday and the day before that, why should I question that it will happen differently tomorrow?

To counter that, one must pause and reflect. Before COVID-19, there space or permission for such reflection was scarce. Many had become so habituated by the rapid pace of business that a learned reliance on routine (and subsequent ethical languor) left many confounded by the COVID-19 crisis. And now that the pandemic has forced a pause (and now that there are actual lives at stake, even for seemingly simply everyday decisions, such as going to the grocery store) we have been given the opportunity—in Ariely’s words—to not waste another crisis.

Because ethics aren’t a fixed point, building responsible, ethical behavior through this crisis will demand productive dialogue—and for a way to understand the implications of each decision made as investors, leaders and global citizens. AFIRE will foster these conversations through ongoing virtual events and forums, as well a series of case studies designed to assess ethical behavior for real estate, communities, and the unpredictable post-pandemic world. Tried and true ethical answers to case studies that have become endemic to our responsible and “routine” business thinking must be examined through a post-COVID lens.

If we learn from one another through dialogue, perhaps we can become better.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Benjamin van Loon leads communications and publications for AFIRE, the association for international real estate investors focused on commercial property in the United States. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of Summit.

NOTES

1. Hugh F. Kelly, Desmond F. McGowan, Steven R. Norris, “Real Estate Ethics in Practical Applications,” Real Estate Issues 44.2 (February 18, 2020): 1-12; https://www.cre.org/real-estateissues/real-estate-ethics-in-practical-applications/

2. Elchanan Rosenheim and Tali Hadari, “A Call to Ethics,” Summit Journal (Spring 2020), https://www.afire.org/summit/calltoethics/

3. G. Andrews Smith, “Craving the Light,” Summit Journal (Summer 2020), https://www.afire.org/summit/cravingthelight/

4. Economist Intelligence Unit, “The Path to Transparency in Alternatives Investing,” The Economist (May 24, 2017), eiuperspectives.economist.com/financial-services/pathtransparencyalternatives-investing

5. Dan Ariely, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty (New York: Harper Perrennial, 2013), 219.

6. Dan Ariely, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty (New York: Harper Perrennial, 2013), 407.

—