When it comes to guards against environmental risk, Boston, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, and Portland are some of the most prepared US cities. What makes them different?

The events of the past year have brought environmental, social, and governance (ESG) front-of-mind for investors and experts in commercial real estate. The growing number of weather-related disasters that produce billions of dollars of property damages, changes in work practices spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, and recognition of the need for equity and diversity have created an urgency for businesses to act on ESG criteria.

Of course, this is not entirely new: over the last decade or more the industry has taken steps by implementing “green” construction standards, retrofitting buildings to reduce energy consumption, and developing other ESG strategies. But in this new environment as the world slowly emerges from a historical pandemic and a year of environmental and political turmoil, addressing ESG has taken on a newfound urgency.

In the US, for example, the new Biden administration has driven change from the top. After his inauguration in January 2021, President Biden immediately rejoined the Paris Agreement, a 2015 accord to reduce emissions and deal with the impact of climate change. He has also instructed regulatory agencies to incorporate into reviews “the interests of future generations,” reversing the policies of the former president, whose regulatory efforts were geared at easing the compliance burden on business.

Federal agencies are taking the environment seriously. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has pledged to create a climate change task force, noting that it is an “existential threat” to the banking system. Regulators may, for example, require banks to account for environmental risk as an element of forward-looking loss projections.

COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE AND ESG

Commercial real estate is focusing on ESG more than ever. Several industry trade organizations have created or expanded working groups to address issues such as environmental risks and diversity in hiring practices, and the recent 2021 AFIRE International Investor Survey (see page 11) shows that ESG is an increasingly urgent concern for global investors. Additionally, the Federal Housing Finance Agency in 2021 started requiring Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to use half of their US$70 billion allotment on multifamily properties that reduce energy consumption.

A growing number of investors are vetting money managers to ensure that capital is deployed by those with concrete ESG policies. Just over half of private equity capital raised for commercial real estate funds between 2018 and 2020 was raised by managers with ESG strategies, according to Preqin. A recent survey by BlackRock of 425 investors that control US$25 trillion of assets found that 88% believe climate change is a risk, and 75% plan to account for ESG risks in their portfolios.1 Collectively the respondents expect to double their allocations to funds with ESG components by 2025, though slightly more than half of the investors surveyed also noted that the poor quality of data is a hinderance to sustainable investment practices.

GROWING RISK TO COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE

Scientists warn that environmental risk is increasing due to global warming, with the last seven years marking the hottest temperatures the earth has reached since the 1800s. The melting of polar ice caps has released water into oceans. Climate scientists say that coastal waters are rising, hurricanes are becoming more frequent and intense, and droughts more common, leading to more risk of wildfires in dry areas and making coastal cities vulnerable to flooding.

Whatever one makes of the science, property investors cannot ignore risks to the bottom line. The annual average of billion-dollar disasters in the US more than doubled to sixteen between 2016 and 2020, up from an average of seven in the prior forty years. More than 400 weather events caused US$268 billion of damage globally in 2020, including a record US$63 billion caused by severe weather events, according to insurance broker Aon.2 Wildfires in the US have caused more than US$10 billion of damage in three of the past four years.

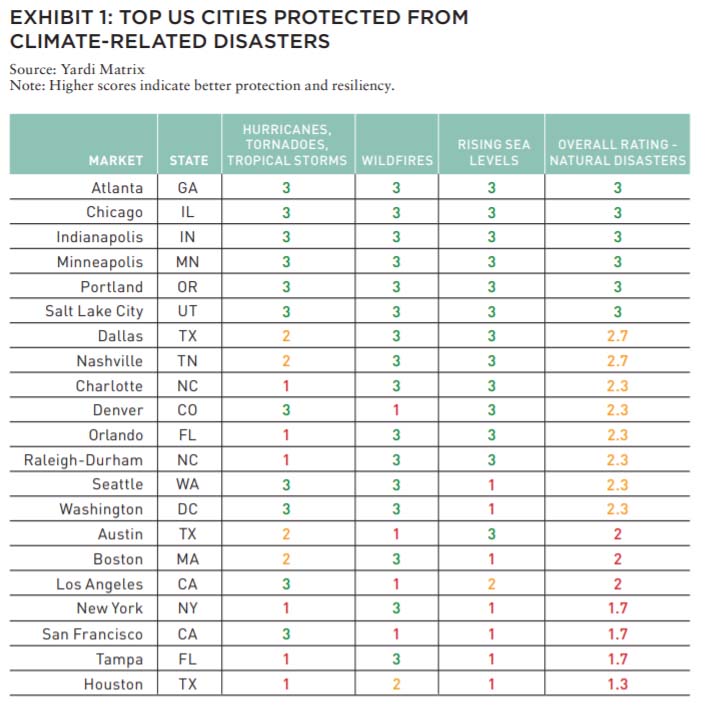

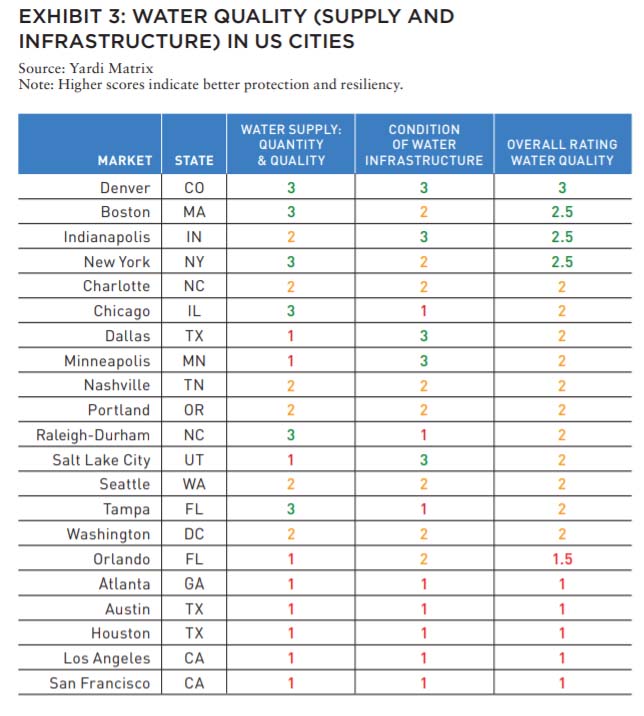

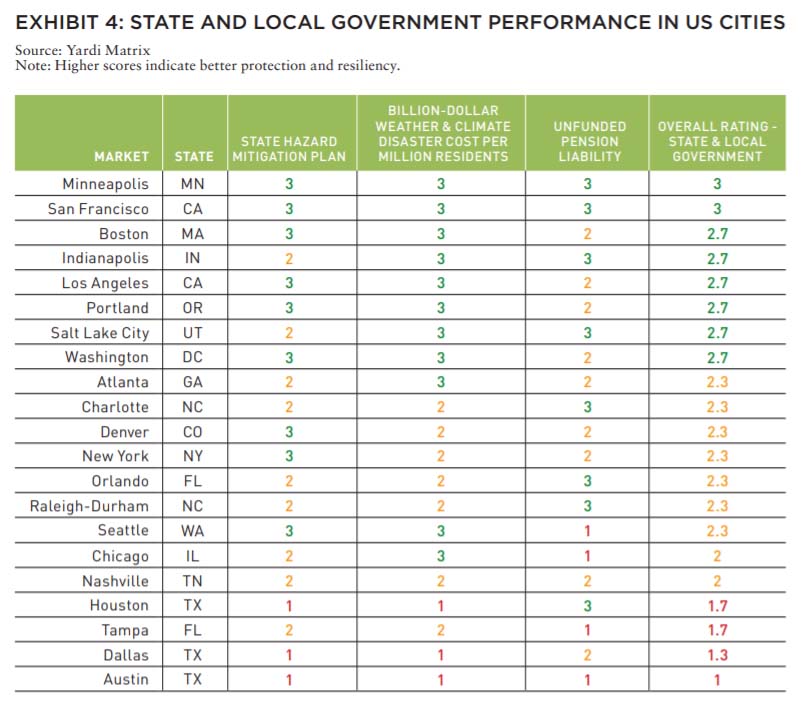

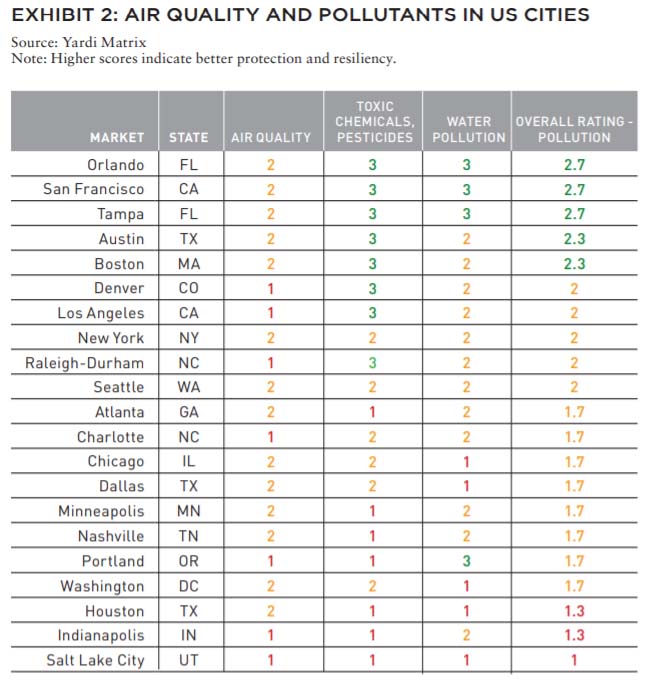

With all this in mind, Yardi Matrix has developed a scorecard for 21 large US metros, using eleven metrics in four categories to create a metro-level analysis of environmental risk. The categories are natural disasters (Exhibit 1), air pollution (Exhibit 2), water quality (Exhibit 3), and the response by state and local governments (Exhibit 4). We assigned grades in each category, green for the least risk, yellow for moderate risk and red for the most risk. We then totaled the grades and came up with scores in each category and the overall environmental risk (Exhibit 5).

NATURAL DISASTERS

Properties are at greater risk in markets subject to natural disasters such as hurricanes, tropical storms or tornadoes, wildfires caused by extreme heat and drought, and potential for flooding caused by rising sea levels. Additionally, insurance is more expensive in high-risk areas.

• Hurricanes, Tropical Storms, Tornadoes: We looked at the number of hurricanes and tropical storms that occurred in each metro over the last hundred years, using data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). This metric was then combined with the average annual number of tornadoes by state, using data from the Storm Prediction Center.

• Wildfires: The wildfire data came from a ULI report titled “Firebreak Wildfire Resilience Strategies for Real Estate,” which used data adapted from Verisk.3 States were ranked by the number of properties at risk from wildfires, alongside the ability of a metro to implement strategies that combat fire risk.

• Rising Sea Levels: Data came from ArcGIS, a geographic information system software maintained by the Environmental Systems Research Institute, a supplier of GIS mapping software. ArcGIS measured the cumulative changes in relative sea level from 1960 to 2018. Cities where sea-level change was two inches (five centimeters) or less were rated green, metros where sea level changed by two to four inches (five to ten centimeters) were rated yellow, and cities where the sea level rose more than four inches (ten centimeters) were rated red.

POLLUTION

Areas with air or water pollution will become unattractive as places to live and work, impacting the value and livability of properties.

• Air Quality: A metro’s air-quality grade was based on the average number of days per year in each market where the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Air Quality Index was at the “unhealthy for sensitives groups” level or worse from 2016 to 2020.

• Toxic Chemicals and Pesticides: Each market was graded based on two different toxic pollutant metrics: (1) the volume of toxic chemicals released into the metro’s environment in 2019, and (2) the average state rate of pesticide exposures from 2008 through 2017.

• Water Pollution: Water pollution poses a risk to people, households, businesses, crops, and animals. Water pollution grades were based on the number of unsafe contaminants detected in the metros’ largest local water utility system.

WATER QUALITY

In addition to water pollution metrics detailed in Exhibit 2, unsustainable depletion of nonrenewable fresh water sources may impact population and economic growth, particularly in arid regions, as water stress and risk increase. The condition of each city’s water infrastructure (e.g., distribution pipelines, sewer systems, and treatment plants) helps to identify water-related risks beyond pollution. Inadequate and deteriorating water infrastructure intensifies the effects of storm damage and creates physical risks, including flooding from sewer overflows and poor drainage.

• Water Supply, Quantity and Quality: Markets were graded based on the quantity and quality of the local water supply, including potential risks such as shortages and contaminants.

• Condition of Existing Water Infrastructure: Markets were graded based on the condition and vulnerability of the local water infrastructure, including the structural reliability, failure events, and need for replacement of lead pipelines.

STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT INVESTMENT

While the onset of natural disasters may be unavoidable, forgoing the opportunity to plan for disasters puts people and assets at risk. In this category we measure whether states have plans and/ or the ability to mitigate environmental risk, and how seriously states take the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) assistance to plan for climate change.

• State Hazard Mitigation Plan: Our grade is based on the Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law report titled “State Hazard Mitigation Plans & Climate Change: Rating the States 2019 Update.”4 The report ranks mitigation plans, with the lowest grades for those that did not recognize climate change or did so inaccurately.

• State Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disaster Cost per Million Residents: Markets were graded based on a report from NOAA titled “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disaster: Overview,” which ranks states on the total cost of climate disasters per million residents from 1980 to 2020.5

• Unfunded Pension Liability: States and cities that have large unfunded liabilities may be constrained in their ability to fund mitigation to environmental risk. Data for each state’s unfunded pension liability was taken from Pew Charitable Trust’s report titled “The State Pension Funding Gap: 2018.”6

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE (SUMMER 2021)

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR / The Housing Issue

AFIRE | Benjamin van Loon

INVESTOR SENTIMENT / Shining Through Darkness

The 2021 AFIRE International Investor Survey underscores a sense of calculated optimism for CRE investment in the year ahead.

AFIRE | Gunnar Branson

ECONOMY / Revisiting Inflation

For commercial real estate investors, inflation fears are real— but are they rational?

Aegon Asset Management | Martha Peyton, PhD

DEURBANIZATION / Herd Community

Uncertainty surrounding remote work and politics suggest a wide range of potential outcomes for big cities, which may upend the long-running megatrend toward urbanization.

Green Street | Dave Bragg and Jared Giles

HOUSING / How to Rebuild

Could an idea to “bring back” New York after the pandemic work in other cities?

Aria | Joshua Benaim

HOUSING / Single Family, Multiple Questions

Institutional ownership in single-family rentals accounts for less than 5% of the segment, but answers to key questions could change start to change that balance.

Berkshire Residential Investments | Gleb Nechayev, CRE

HOUSING / Institutionalizing Single Family

Over the past two decades, the single-family rental industry has evolved into an institutional-caliber asset class—so where is the sector going next?

Tricon Residential | Jonathan Ellenzweig

HOUSING / Build-to-Rent Boom

The future is bright for build-to-rent and institutional investors are increasingly looking at investing in this sector.

Squire Patton Boggs | John Thomas and Stacy Krumin

OFFICE / Recovering the Office

While most agree that the office sector has a difficult road ahead, there is less consensus about future demand in the sector. What are the indicators investors should be tracking?

Barings Real Estate | Phillip Conner and Ryan Ma

OFFICE / London Calling

With Brexit and pandemic resolutions coming into focus, pricing disparities could dissipate based on improved cross-border liquidity and cap rate compression in the London office market.

Madison International Realty | Christopher Muoio

LOGISTICS / Supply Change

Urbanization, digitalization, and demographics are the key trends to watch for understanding the future of logistics real estate.

Prologis | Melinda McLaughlin and Heather Belfor

CLIMATE / Accounting for Environmental Risk

When it comes to guards against environmental risk, Boston, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, and Portland are some of the most prepared US cities. What makes them different?

Yardi Matrix | Paul Fiorilla, Claire Anhalt, and Maddie Harper

ESG / Putting People First

Though “impact investing” is no longer totally distinct from investing in general, investors still have a lot of work to do for fulfilling the social and governance aspects of ESG expectations.

Grosvenor Americas | Lauren Krause and Brian Biggs

MULTIFAMILY / Influencing Multifamily

As we come out of the pandemic to a new economy, it seems likely that the creator economy will continue to grow. This will have a major impact on the multifamily sector.

citizenM Hotels | Ernest Lee

TALENT AND RECRUITMENT / Enhancing Life Sciences

As the global life sciences sector continues to grow in real estate, highly specialized skills and experience will be the keys to success.

Sheffield Haworth | Max Shepherd and Jannah Babasa

EDUCATION / Real Estate Education Goes Global

The evolution of global real estate education over the past three decades will be integral to developing a rich pipeline of talent for the future of commercial real estate.

Georgetown University | Julian Josephs, FRICS

FINAL GRADES: ACTION COUNTS

Based on our methodology, four metros stood out as having the least environmental risk: Boston, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, and Portland. The commonality was their location in states with policies and leadership that take environmental risk seriously.

The five lowest-ranked metros include three in Texas (Houston, Austin, and Dallas), along with Tampa and Los Angeles. The grades for Texas metros were dragged down by low scores in the natural disasters and government response categories. Both of those problems were on display in the severe winter storm in February 2021 that led to 4.5 million residents losing power and food and water shortages. Some 151 residents died in winter-related storms, according to the Texas Department of Health and Human Services.7

The Texas storms are a demonstration of the stakes. Texas has reaped the benefits of deregulation and low taxes and utility costs, but utility providers’ lack of investment to winterize the power grid left the state unprepared to handle extreme weather. The result was a disaster and an estimated US$20 billion in costs.

STARTING THE CONVERSATION

These rankings are not meant as investment advice. ESG is a complicated topic that encompasses a wide range of specialties, of which we focused on one: environmental risk. Data in this emerging field remains difficult to obtain and measure. The field is in its infancy, with better data and metrics yet to come.

Some will no doubt question the categories we chose, the methods we used to grade metros, or what constitutes a proper response to ESG issues. This is our intention. Our rankings are not meant as a final word on the topic, but rather, a first attempt to understand the issues and develop a model for how to approach the topic— which is of increasing importance for commercial real estate.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Paul Fiorilla is Director of Research, and Claire Anhalt and Maddie Harper are Senior Analysts, for Yardi® Matrix, which offers the industry’s most comprehensive market intelligence service for multifamily, office, self-storage, and vacant land properties.

—

NOTES

1. “2020 Global Sustainable Investing Survey.” BlackRock. Accessed June 22, 2021. blackrock.com/corporate/about-us/blackrock-sustainability-survey

2. “Weather, Climate & Catastrophe Insight: 2020 Annual Report.” Aon. Accessed June 22, 2021. aon.com/global-weather-catastrophe-natural-disasters-costsclimate-change-2020-annual-report/index.html

3. “Firebreak: Wildfire Resilience Strategies for Real Estate.” 2020. ULI Knowledge Finder. Accessed June 22, 2021. knowledge.uli.org/en/Reports/Research%20Reports/2020/Firebreak%20Wildfire%20Resilience%20Strategies%20for%20Real%20Estate

4. Alder, Dena P. and Emma Gosliner. 2019. “State Hazard Mitigation & Climate Change: Rating The States 2019 Update.” Columbia Law School. climate.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/Adler%20Gosliner%202019-09%20SHMP%20Report%20Update%20ed.pdf

5. “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters Overview.” National Centers For Environmental Information. Accessed June 22, 2021. ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/

6. “The State Pension Funding Gap: 2018.” PEW Research. June 11, 2020. pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2020/06/the-statepension-funding-gap-2018

7. “COVID-19 Variants – June 23, 2021.” Texas Department of State Health Services. Accessed June 22, 2021. dshs.texas.gov/news/updates.shtm#wn